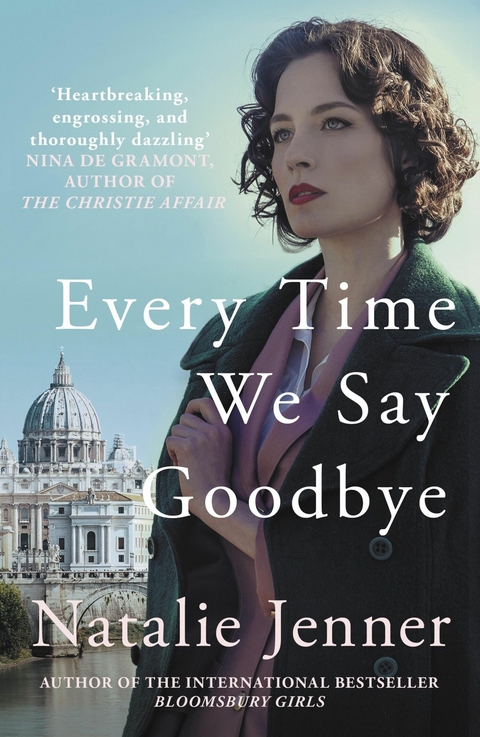

Every Time We Say Goodbye (eBook)

320 Seiten

Allison & Busby (Verlag)

978-0-7490-3016-2 (ISBN)

Natalie Jenner's previous novels, The Jane Austen Society and Bloomsbury Girls, were international bestsellers. Born in England and raised in Canada, Natalie has been a corporate lawyer, career coach and, most recently, an independent bookshop owner. She lives in Ontario, Canada with her family and two rescue dogs.

Natalie Jenner's debut novel The Jane Austen Society was an instant international bestseller. Born in England and raised in Canada, Natalie has been a corporate lawyer, career coach and, most recently, an independent bookstore owner. She lives in Ontario, Canada.

Opening night for Vivien had gone like a dream.

All the things that could have gone wrong, or had done in rehearsals, failed to transpire. The audience had laughed at the right places and cried at the end. There had been four curtain calls for the only female-authored play on the London stage that season, and extended cheering after the heavy red velvet curtain had fallen to the floor with a final, glorious thud.

Vivien could still hear the roar of the crowd as she stood on the second floor of Sunwise Turn, the Bloomsbury bookshop that helped finance her writing efforts. As a significant shareholder in the shop, she drew a nice little dividend each year and spent several afternoons a week behind the till. She preferred that time – the leisurely, not-even-sure-why-I-popped-in-here energy compared to the rattle of the morning customers who arrived armed with a bizarre array of requests. Tabitha Knight, their youngest employee, was more adept at fielding those, with her innocent face and subdued manner.

It was long past midnight, and the reviews of Empyrean, Vivien’s second play, would soon hit newsagent stands throughout the West End. Alec McDonough, her longtime editor, popped out during the after-party festivities to lug a pile of the morning newspapers back. Her first play had opened two years earlier and not been granted its fair share of attention from audiences or critics alike; the reception tonight, however, had been undeniably positive. Vivien felt inside that strange mix of anticipation and dread that was the artist’s lot. The entirety of years of work now rested in the ink-stained fingers of a handful of notoriously viperish critics.

As Vivien stood in a corner of the second-floor gallery, nervously sipping a crystal glass of brandy, Sir Alfred Jonathan Knox finally made his move.

‘Do you think you shall keep at your writing?’

Vivien turned to him in surprise at the familiarity of the question. They had only been introduced backstage that night, her friend Peggy Guggenheim extolling Sir Alfred’s philanthropic efforts as he stood fidgeting with embarrassment next to her.

‘I mean …’ He cleared his throat, and she noticed that his hands were jammed into the pockets of his black dinner jacket. ‘I only meant that, if you were to settle down …’

‘Oh, I’ll never settle down.’

‘I’m sorry?’

‘I might marry – most people do, after all – but it won’t be to settle.’

He looked so confused by her words that she felt almost sorry for him. ‘Perhaps settle is not the right term …’

Vivien had had her share of romantic disappointments over the years, but watching a man struggle to pin down a single word, relative to her own skill in that area, was particularly disheartening. Sir Alfred’s plain-but-pleasant-enough features shifted quickly from confusion to concern until he looked ready to take another tack. He’s going to bring up those children again, she thought to herself with a grimace, then felt sorry. He was, after all, a wonderful civic example, known throughout the nation for both industrial success and philanthropic effort.

‘The children come to Devon on the weekends, to ride and scout and take other lessons. For years we have done our best – my late wife and I, that is – to give them a home of sorts, a place of their own to, ah, settle.’

Vivien had to laugh inwardly at his use once again of that term. At the same time, she felt awful. She should consider a man like Sir Alfred, so generous and charitable and eager to please. Why did his goodness irritate her so? She was inclined to see it as a mask of some kind, a diversion from what he really wanted. Of course he wanted to help the refugee children in his care, but he also wanted people to think of this largesse when they thought of him: why else would he talk of it so? More than anything, he wanted to be thought of. He clearly needed another wife. But if Vivien were ever to marry a man like Sir Alfred, she would most certainly need to keep writing, given the limited conversation.

Alec’s footsteps could be heard coming back up the stairs. He reached the landing, and from across the room Vivien instantly recognised the look of disappointment and quiet panic on his face.

‘Oh God,’ she muttered while her mentor, Lady Browning, came over to grab the top news copy from Alec who stood frozen in the doorway.

All the women – for, as usual, they were mostly women up there, lounging about the bookshop’s second floor – watched as Lady Browning, with a practised hand, tore open the Daily Mail to the exact page, then silently mouthed the words as she read.

‘Insufferable prigs!’ She threw the paper down and pointed an accusatory finger at Alec, who helplessly shrugged as the male representative closest to her in proximity. The few other men present had already intuited the dangerous mood about to descend and would normally have plotted their retreat, but for being trapped by the late hour and the chivalry owed their dates.

‘I can’t look,’ Vivien muttered while Peggy Guggenheim stepped forward to pick the paper back up. A longtime patron of the shop, the famous art collector had arrived that afternoon from Venice in time for both Vivien’s opening night and the Christmas social season. ‘No, wait.’ Vivien looked down, letting her long, dark hair fall about her face like a curtain. ‘Read it to me.’

‘“Empyrean’s portrayal of a group of village women fending for themselves during the war, who fall into a utopian society they will stubbornly refuse to dismantle, shouts its political agenda with all the nuance of a harpy. Miss Lowry’s idea of a happy ending may leave much to be desired, yet unfortunately remains the only positive aspect of this often crude, simplistic sophomore effort premiering last night at the Aldwych.”’

‘It’s not supposed to be a happy ending.’ Looking back up at Peggy, Vivien rolled her eyes in irritation. ‘And it’s supposed to be abstract.’

‘Crude my word,’ Guggenheim practically spat as her Calder-designed earrings swung violently about her head. ‘If you were a man, they’d call it progressive.’

‘What will Spencer say?’ Lady Browning, better known as author Daphne du Maurier, asked in reference to her and Vivien’s agent.

‘I believe his exact words this time were “do or die.”’ Vivien flopped down onto one of the large wingback chairs near the fireplace that warmed the gallery while Peggy Guggenheim took the matching chair next to hers. ‘And as you know, he’s not one to mince them.’

Tabitha Knight silently entered the room with a pot of tea on a silver tray and quickly looked about at the downcast faces. She had a watchful manner, an artistic eye, and little enthusiasm for books. Tabitha’s adoptive mother, despairing over her daughter’s lack of interest in anything except art, had suggested the sales assistant position at Sunwise Turn to get her ‘out of her head.’ Tabitha, however, was happiest alone in the second floor’s gallery and event space, where several invaluable pieces from Peggy Guggenheim’s personal art collection were on display. For most of that night, Tabitha had been contemplating Guggenheim’s latest loan to the shop, Boy Smoking by Lucian Freud. Vivien had overheard the young woman commenting on the portrait’s effectiveness due to its lack of context, and Guggenheim responding that part of Freud’s emerging genius was how he severed the body from the soul. Vivien had listened curiously because when she looked at the painting, all she saw was a floating head.

‘Come to Italy,’ Guggenheim was now saying to Vivien at her side, tracing circles in the air with the length of her cigarette holder. ‘My friend Douglas Curtis is on his way there, trying to evade those idiotic McCarthy hearings. He’s got a two-picture deal to direct and an unfinished script.’

‘They’ll just accuse me of trying to escape.’ This was how Vivien always referred to the London drama critics, the ubiquitous they that her mentor, du Maurier, and other writers had warned her about.

‘One doesn’t go to Italy to escape the past, but to acquire one,’ Peggy replied with an outsized wink. Guggenheim did everything on an ambitious scale, from her Carnival parties and huge abstract earrings to her lifelong enmity towards those who crossed her. Maybe the secret to living a large life, thought Vivien in despair, was to go out and do exactly that.

‘I shall write to Douglas,’ Guggenheim continued. ‘Imagine filming anything without an ending in sight. It would be like trying to paint a peach from a bowl of pears.’

Out of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Historische Romane |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Schlagworte | 1900s • 1950s • Bloomsbury Girls • Cinecittà • Cinecittà studios • Film • Italy • Natalie Jenner • Playwright • Post-War • Romance • Rome • The Jane Austen Society • Twentieth-Century • Vatican • war |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7490-3016-X / 074903016X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7490-3016-2 / 9780749030162 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 675 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich