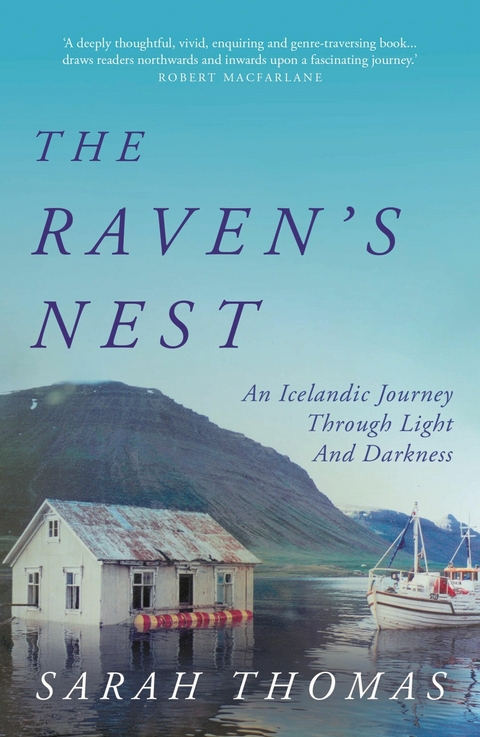

The Raven's Nest (eBook)

336 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-670-7 (ISBN)

Sarah Thomas is a writer and filmmaker. Her films have been screened internationally, and she is a contributor to the Dark Mountain journal. Her writing has also appeared in the Guardian and the anthology Women on Nature edited by Katharine Norbury.

Sarah Thomas is a writer and filmmaker. Her films have been screened internationally, and she is a contributor to the Dark Mountain journal. Her writing has also appeared in the Guardian and the anthology Women on Nature edited by Katharine Norbury.

Landing

May 2008

My neck aches as I react to the ‘bong’ prompting passengers to fasten their seat belts. My face has been pressed against the oval window for thirty minutes straight, turning only briefly to say, ‘tea, please’. Beyond the condensation of my breath and the delicate ice crystals forming on the outside of the window, I have been looking out at a translucent blue sky that seems stretched thin by the weight of profuse sunlight. Beneath it, the sea is a choppy teal blue as if painted by a stippled brush and the shoreline meets the mountains frankly. Their opaque indigo bulk rises sharply and they are flat on top as if a giant has taken a sword to them. It is an Arctic palette, an infinite blue, and the landscape appears as wild and unsullied as Earth does from space. Though I know pristineness is an illusion in our times, for the moment I am enrapt. I am heading the furthest north I have ever been: sixty-six degrees latitude. Even in late May, snow swirls on the mountaintops and rests in shaded hollows. Since lifting off from Reykjavík I have not noticed any other cities or even aerial towns; only settlements I would describe generously as villages, and no more than three of them.

Having started the journey in London, I am on my way to the small town of Ísafjörður – the ‘capital’ of the Westfjords – in the top northwest corner of Iceland, which for reasons none of the delegates will fully understand, is the unlikely and awe-inspiring location for a conference of visual anthropologists. I will be presenting my MA graduation film After the Rains Came: Seven short stories about objects and lifeworlds, an observational documentary I made in Kenya, where I spent the latter part of my childhood and adolescence.

Observational documentary: the ‘fly on the wall’ style where the footage works to suggest that the filmmaker is not there at all. A film shot on the Equator, brought to the Arctic. The view from the plane’s window could not be more different to the world of my film: the cracked earth, coloured beads and giant euphorbia trees of Kenya’s Samburuland that will soon be projected on a screen down there somewhere.

I have been invited to stay with some friends of a friend, and as I gaze out at the wilderness, I feel fortunate to have connections in this remote place. I wrote to them a while back thanking them for their kind offer of a bed, and in response received ‘directions’: a photograph taken from the side of a mountain, looking down onto a long narrow fjord flanked on the opposite side by another steep-sided mountain – a trough of rock filled with sea. A spit curled out from the foreground to part way across the mouth of the fjord, forming a sheltered harbour. Brightly coloured houses were clustered on the spit and the few other flat surfaces of land. Their spread was contained by the clutch of the landscape, as if gravity itself pulled the houses towards the sea. Where construction ended, wild nature abruptly began – loose boulders on tussocky heaths and funnels of scree sloping up to terraced cliffs of basalt. This was altogether different from the patchwork of green squares and vast masses of concrete that is England from above. Over on the far shore at the bottom of the fjord they had drawn a yellow circle, and the word ‘Airport’. Towards the foot of the spit was another yellow circle: ‘Salvar and Natalía’. Their house was oxide red – I could see that from the photograph. My rational city brain was slightly wary of the lack of further information, but my intuitive self could see that this was the only information I would need. I liked these people: visual and concise.

As the twin-propeller Air Iceland plane suddenly banks sharply left, I recognize that this is that fjord, that spit seen from the other side. I imagine my hosts standing there taking that photograph, as I align its viewpoint with what I can see. I realize I might even be able to spot the house I am going to. My search for it is quickly replaced by alarm at the proximity of the wing tip to the mountain. It is a very close shave indeed, and a good thing they are standing there only in my imagination. I briefly look around at the other twenty passengers on this packed flight and cannot fathom how some of them are reading a newspaper. This moment is both frightening and phenomenally beautiful. We descend to the bottom of the fjord and bank steeply again. Somebody has mown a large HÆ into their hay meadow – a greeting to be seen from the sky. We land and bounce onto the airstrip facing towards the mouth of the fjord, from which we have just come. ‘How is that even possible?’ I think to myself. I would later learn that Ísafjörður is one of the most challenging airports in the world in which to land.

We disembark into the miniature single-storey terminal where passengers are waiting to board the same plane back to Reykjavík. We mingle. There are two flights here a day, cruising back and forth across this lava, these mountains and these fjords: Reykjavík – Ísafjörður – Reykjavík – Ísafjörður – Reykjavík. Passengers departing Ísafjörður don’t need an app to tell them if the flight is running on time. They just look up in the sky when they hear the engine rumbling and hop in their cars to curl around the bay to the airport, playing plane chase. I would later learn that the radar tower operator is also a carpenter in town, and simply cycles over to the airport when a flight is due, then returns to work when he has seen the plane safely off again.

It turns out that several fellow delegates are on the same flight and there is a coach waiting for us outside. White-bodied birds I have not seen before wheel, combative like throwing stars, above the car park showering the air with cries of kriiiia kriiiia. The passengers wrestle their black luggage into large four-wheel drives. The mountains tower above us and insist that we are small. You can spot those who do not live here: their mouths hang agape over the necks of their Gore-Tex jackets, and their luggage has lost all its importance. The locals seem to have developed an immunity to the landscape’s power, but I imagine it is more complex than that.

We board the coach and a tall frowning man with a grey side parting and a shiny face fusses and breaks intermittently into nervous laughter. ‘Hæ. I’m Valdimar,’ he greets us repeatedly. He is clearly the one in charge, but it looks like this is the most people he has had to organize in a while. It is hot, and I have come only with jumpers. The sun feels near. It is bright and beats on me through the large glass window, as if curious and eager to illuminate everything it can. I drink in the scene through squinted eyes and feel both sleepy and enormously awakened.

We round the bottom of the fjord, passing on our left a grid-like housing development and a supermarket with gaudy signage of yellow with a bright pink piggy bank: Bónus, it is called. Behind it all is a long, lush valley lined with lupine and speckled with brightly coloured wooden cabins. Midway up the valley I can make out a large waterfall that in another place would be reason enough to come here, and a small square plantation of some kind of pine that Valdimar refers to as the local ‘forest’. There is a long, man-made sharp-edged ridge separating that valley from the buildings along the fjord’s edge and he tells us that it is an avalanche guard. In the harbour lagoon to our right, flocks of eider ducks bob among reflected impressions of the sun-glowed mountains – morphing orange and green fragments floating leaf-like in the black glassy water. We pass a scattering of houses, then the town proper seems to begin. Valdimar takes the microphone again and points out in quick succession a kindergarten, a school, an old people’s home, a hospital and, across the road, a church and cemetery.

‘I suppose they have to be ergonomic with town planning here!’ an Italian academic in the seat behind me chuckles. ‘Look, a whole life in 500 metres.’

As we approach the spit on which the oldest part of the town is built, I see that the houses are all clad in brightly coloured corrugated iron, with differently coloured iron roofs. In just one street I see cornflower blue, deep red, egg yolk yellow, black. It gives the town an air of playfulness – I imagine the people here to be happy and daring. The coach slows to a halt by the church and I take my photo directions to Valdimar. It is a map made for a bird or a hiker at height. I am at the wrong angle here.

‘Do you know where this house is?’ I ask him. ‘That’s where I’m staying.’

‘Whose house is it? Salvar and Natalía? Ah yes, I know them.’

He reaches for his mobile phone and scrolls for their number. He doesn’t have it. He inspects the photograph a little more closely. ‘… Sólgata, Hrannargata, Mánagata, Hafnarstræti… Ah, that is this one.’ He points at the street we are on. That was easy.

Twenty metres later I am standing in front of an oxide-red house, conjoined with a leaf-green house painted with a mural of giant dandelions. From what I have seen of Icelandic homes from the outside, it seems to be typical to make displays of ornaments in the windows, to delight those walking past on the street, and perhaps to give an inkling of the people who live inside. In the moments between my knocking...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.7.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Amy Liptrot • ash cloud • Barry Lopez • Climate • Divorce • Ecology • Environment • Eyjafjallajökull • Fitzcarraldo • Glacier • Iceland • Macfarlane • marriage • Memoir • Nan Shepherd • Nature • northern lights • outrun • Raven • Raynor Winn • Reykjavík • robin wall kimmerer • sarah thomas • Travel • volcano • Westfjords |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-670-0 / 1838956700 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-670-7 / 9781838956707 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich