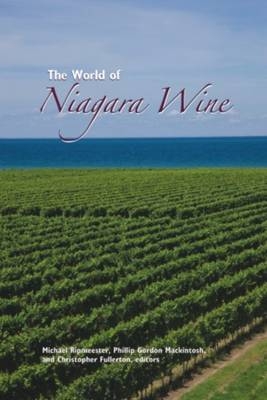

World of Niagara Wine (eBook)

295 Seiten

Wilfrid Laurier University (Verlag)

978-1-55458-406-2 (ISBN)

The World of Niagara Wine is a transdisciplinary exploration of the Niagara wine industry that celebrates and critiques the local wine industry and situates it in a complex web of Old World traditions and New World reliance on technology, science, and taste as well as global processes and local sociocultural reactions. In the first section, contributors explore the history and regulation of wine production as well as its contemporary economic significance. The second section focuses on the entrepreneurship behind and the promotion and marketing of Niagara wines. The third introduces readers to the science of grape growing, wine tasting, and wine production, and the final section examines the social and cultural ramifications of Niagara s increasing reliance on grapes and wine as an economic motor for the region. Preface by Konrad Ejbich.

One

The Early History of Grapes and Wine in Niagara

Alun Hughes

The impact of the War of 1812 on the Niagara Peninsula was devastating. Between October 1812 and November 1814, the Peninsula was the scene of frequent action. Major battles were fought at Queenston Heights, Fort George, Stoney Creek, Beaverdams, Chippawa, Lundy’s Lane, and Fort Erie, and at other times the Peninsula experienced severe disruption from ransacking soldiers and Native warriors. Not surprisingly, many farmers and other property owners suffered major losses as houses and barns were burned, fences torn down, crops trampled, livestock killed, and household items taken. This is very evident in the war loss claims submitted after the return of peace, not only for damage caused by the Americans but also by the British and their Native allies.

One of these claims was submitted by Thomas Merritt (Figure 1.1) of Grantham Township, father of William Hamilton Merritt of Welland Canal fame. The elder Merritt’s farm was located east of Twelve Mile Creek at the southern tip of Martindale Pond, now a part of St. Catharines.1 His losses were fairly typical—buildings torched, fences and crops destroyed, and items stolen (including a chestnut horse, two stoves, and two feather beds). He also lost fruit trees and grape vines.2 The fact that Merritt claimed for the vines suggests that they were not just growing wild, which makes this one of the earliest references to grape culture in the Niagara Peninsula.

Elizabeth Simcoe, wife of John Graves Simcoe, first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, mentions grapes and vines several times in her diary. But although she spent almost two years at Newark (later Niagara) between 1792 and 1796, all her references come from outside the Peninsula—for example, across the Niagara River at the “Ferry House opposite Queenston,” where she “breakfasted in the Arbour covered by wild Vines,” and at York (later Toronto), where she “gathered wild grapes … pleasant but not sweet.” She even mentions one case of impromptu winemaking, when soldiers laying out Dundas Street “met with quantities of wild Grapes & put some of the Juice in Barrels to make vinegar … it turned out very tolerable Wine” (though the reference to vinegar makes one wonder what sort of wine this was).3 Making wine from wild grapes was rare, however, and most of the wine consumed in early Upper Canada was imported. Thus when Scottish traveller Patrick Campbell was entertained by Mohawk leader Joseph Brant at his home on the Grand River in 1792, it was port and Madeira they savoured, not locally produced wine.4

Figure 1.1 Thomas Merritt

Source: Wm. Hamilton Merritt, Memoirs of Major Thomas Merritt, U.E.L., 1909.

Early references to grapes and winemaking in the Niagara Peninsula are few (Merritt’s war claim is a rare exception), which may seem strange given the present-day importance of the Niagara wine industry. However, it is understandable given the area’s history. The purpose of this chapter is to outline that history, and to consider agriculture and the grape and wine industry in particular in the broader context of the political and economic developments of the time. The history falls into three phases: the Pre-Loyalist Period prior to the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783; the Pioneer Period from 1783 to the end of the War of 1812 in 1815; and the Postwar Period from 1815 to a few years beyond Confederation in the early 1870s.

The Pre-Loyalist Period

When Europeans first made contact with Native peoples in what is now Canada in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the Niagara Peninsula was inhabited by the Neutral Nation. Their primary homeland was in the Hamilton area, but their territory extended west as far as the Thames River and east for a short distance across the Niagara River. They formed part of the broader Iroquoian family, which included the Huron and Petun tribes around Georgian Bay and the Iroquois of the Finger Lakes (the latter comprising the Seneca, Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, and Mohawk of the Five Nations or Iroquois Confederacy).5 The Neutral were so named by French explorer Samuel de Champlain (Figure 1.2) because they refused to take sides in the long-standing hostilities between the Huron and the Iroquois (though they were far from peace loving when it came to other tribes).6 What they called themselves is not known.

Figure 1.2 Samuel de Champlain

Source: H.P. Biggar, ed., The Works of Samuel de Champlain, Vol. 1, 1922.

Unlike the tribes of the Algonquian family, which occupied land further north in what is now Ontario, the Neutral and other Iroquoians supported themselves by farming as well as hunting and fishing. They employed a form of shifting agriculture based mainly on the cultivation of Indian corn, squashes, and kidney beans, occupying a site for two or three decades until its productivity declined. This allowed them to live in semi-permanent villages, typically a group of longhouses surrounded by palisades. One of these, dating from the early seventeenth century and possibly a regional capital, was the so-called Thorold Site, located on the Escarpment brow near Brock University.7 Important Neutral burial sites at Grimsby and St. Davids date from the same era. Archaeological evidence aside, our knowledge of the Neutral comes mainly from the writings of early French missionaries. Thus Recollect Joseph de La Roche Daillon visited Neutralia in 1626, as did Jesuits Jean de Brébeuf and Pierre Chaumonot in 1640–41, though whether they ventured into the Niagara Peninsula is debatable.8

Such missionaries, together with fellow French explorers and administrators, were responsible for the first references to grapes and wine in Canada (unless, of course, one accepts the claim by some that Norseman Leif Eriksson gave the name Vinland to Newfoundland in 1001 because of wild grapes growing there). Sailing up the St. Lawrence in 1535, Jacques Cartier saw “so many vines loaded with grapes that it seemed they could only have been planted by husbandmen,”9 and in 1603 Samuel de Champlain reported “many vines, on which there were exceedingly fine berries,” from which they “made some very good juice.”10 Champlain speculated about making wine, but Recollect Nicolas Viel, writing from Huronia in 1623, provided the first report of anyone doing so: “When the wine which we had brought from Quebec in a little barrel of twelve quarts failed, we made some of wild grapes which was very good.”11

Father Viel and other missionaries needed wine, of course, to celebrate mass. Sacramental wine was routinely imported from Europe (Spanish wine apparently being a favourite among the Jesuits), but when it was not available, the only choice was to make one’s own. This was especially common when travelling long distances. In 1669, Sulpician missionaries Francis Dollier de Casson and René Bréhant de Galinée made wine, “as good as vin de Grave,” while wintering on the Lake Erie shore in the Port Dover area during a year-long circumnavigation of southern Ontario.12 Recollect Louis Hennepin makes several references to making wine during his North American travels in the late 1670s, on one occasion availing himself of the “wild vines loaded with grapes” near the Detroit River. (Later, however, something went amiss, for in 1680 he complains of not having been able to celebrate mass for nine months for lack of wine!)13

But wine was not just made out of necessity. Isaac de Razilly, governor of Acadia, writing to Marc Lescarbot, a French writer, lawyer, and traveller, in 1635, says that “The vines grow wild here and from the wine that was made from them we said mass”;14 a year later, Jesuit Paul Le Jeune writes from Huronia, “In some places there are many wild vines loaded with grapes; some have made wine of them through curiosity; I tasted it, and it seemed to me very good.”15 In neither of these cases is there any suggestion that imported wine was unavailable. Indeed, in the case of Acadia, imported grape vines may have been available also, for Razilly goes on to say that “Bordeaux vines have been planted that are doing very well,” which may be the very first mention of grape cultivation in Canada. Others saw no need for imported vines, as witness Jesuit Jacques Bruyas, writing from Iroquois country in 1668, reports: “There are also vines, which bear tolerably good grapes, from which our fathers formerly made wine for the mass. I believe that, if they were pruned two years in succession, the grapes would be as good as those of France.”16

None of these early sources mention Native peoples being involved in wine-making, because, in eastern North America at least, they never seem to have made wine. To quote Gabriel Sagard, who was with Viel in Huronia in 1623, “The Savages do eat the grape, but they do not cultivate it and do not make wine from it”—this because they lacked “the imagination or the proper equipment.”17 We may assume that what Sagard said about the Huron applied also to the Neutral in the Niagara Peninsula. They no doubt ate the wild grapes growing here, and possibly even made juice, but they never went as far as making wine.18

But the days of the Neutral were numbered anyway. In the late 1640s, the continuing antagonism between the Huron and Iroquois erupted into full-scale...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.7.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Getränke |

| Technik ► Lebensmitteltechnologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-55458-406-X / 155458406X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-55458-406-2 / 9781554584062 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich