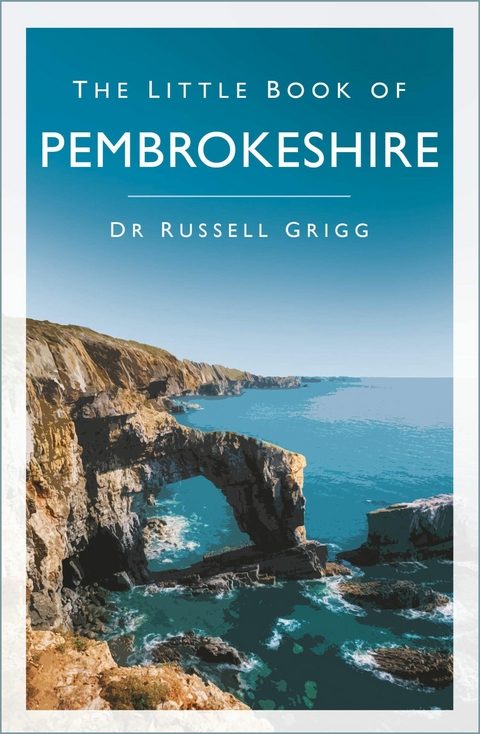

The Little Book of Pembrokeshire (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-391-1 (ISBN)

DR RUSSELL GRIGG is a senior lecturer in history and has been the programme director for MA southwest Wales, covering Pembrokeshire. He has a PhD in local history and has held courses for Pembrokeshire teachers on local history. He has a strong knowledge of the county, having published popular and academic articles and books for local magazines such as Carmarthenshire Life and the University of Wales Press. He is well acquainted with source material, as he has co-directed the University's MA course in local history. He gives talks to local history societies and contributes to media programmes based on Carmarthen and the area, such as Who Do You Think You Are with Griff Rhys Jones, ITV's Our Town series (Carmarthen) and the BBC Radio 4 Long View series on the Llanelli School Strikes. He is an experienced writer having published 15 books, one of which was The Little Book of Carmarthenshire.

2

THE IRON AGE CELTS, C.600 BC–AD 48

The oldest surviving written references to what is now Wales and Pembrokeshire appeared in the second century AD when the Greek cartographer Claudius Ptolemy mentioned the Demetae, the Celtic tribe, whom the Romans say occupied south-west Wales. We know hardly anything about these people, although more generally the Classical writers regarded the ‘Keltoi’ or ‘Celtae’ as ignorant, uncivilised ‘barbarians’ who babbled, making unintelligible sounds (‘bar bar bar’). Unfortunately, we do not know what the Celts thought because they left no written records. Their culture emphasised storytelling, metal and craftwork rather than reading and writing.

The Celts may have lived up to their reputation for being ‘madly fond of war, high-spirited and quick to battle’. But they were also highly skilled craftsmen, evidenced by surviving brooches, cauldrons, decorative pins, shields and swords, which are exhibited in the National Museum of Wales, the British Museum and museums across Europe. Goldsmiths produced stunning torcs, or necklaces, which provided the wearer with divine protection and a sense of mystery, wealth and status.

The Celts were also excellent horsemen and charioteers, masters of wheeled vehicles. In 2018, a local metal detectorist found an Iron Age chariot burial in an undisclosed field in south Pembrokeshire, the first of its kind in Wales. It not only transformed his life, with reports of him receiving a six-figure treasure payment, but it also enhanced our understanding of how such technology and burial practices spread – all of the other British chariot burials found thus far have been unearthed in northern England, notably Yorkshire. The likelihood is that the chariot was owned by a local tribal chief.

The Celts are famous for their hillforts, which offered protection for farms and a place to store food, while also acting as a centre for social activities. There is evidence for around 600 hillforts in Wales, more than 100 of which are found in Pembrokeshire. Most of these were probably small in scale, supporting a family or two. Carn Alw, on the western side of the Preseli Hills, served as a small, enclosed space, possibly a summer grazing retreat or refuge. In contrast, Foel Drygarn (‘hill of three cairns’), on the top of the Preseli Hills, covered several hectares and was likely a tribal headquarters accommodating a couple of hundred people.

The large stone hillfort on Carn Ingli, with its array of ramparts, enclosures and huts, was first mentioned in the twelfth century as the site where St Brynach reputedly communed with angels. But far more common than this were smaller hillforts defended by banks and ditches and limited to less than 1 hectare. Promontory forts jutted out and incorporated steep cliffs as part of their natural defences. Around 100 or so of these have been identified, such as Dale Fort and Porth y Rhaw.

Hillforts were built for shelter and protection. Among the various defensive features of the larger hillforts was the cheval de frise, consisting of upright stones placed in a band outside the main defences with the aim of halting or slowing down the enemy’s advancing chariots. Excavations at the partially reconstructed Iron Age settlement at Castell Henllys (‘Old Palace’), near Eglwyswrw, show that its cheval de frise was preserved under a later defensive bank, suggesting that it was only meant as a temporary measure to be covered over once more substantial resources were available for defence. Several thousand slingstones have been found at Castell Henllys. These were an effective weapon in ancient times, highlighted in the biblical story of David slaying Goliath. An experienced slinger could kill or inflict a serious injury at a distance of 60m or more.

Castell Henllys provides modern-day visitors with a sense of what life might have been like 2,000 years ago, living among the Demetae. Unusually for a promontory fort, the high ground is at the bottom of the site, while the surrounding defences are hidden in trees. The site is approached through leafy woodland and ascends to an open area of just over an acre. This is small in comparison to other Iron Age settlements. Maiden Castle (Dorset), for example, covers 47 acres.

Castell Henllys contains four roundhouses and a granary, which have been carefully reconstructed on the original Iron Age foundation postholes. Two of the four roundhouses have in recent years been dismantled, re-excavated and reconstructed. One of the roundhouse roofs has been rethatched twice.

Archaeologists have been working on the site for nearly forty years. They calculate that the construction of the largest roundhouse alone required thirty coppiced oak trees, ninety coppiced hazel bushes, 2,000 bundles of water reeds and 2 miles of hemp rope and twine, necessary for forming its rafters, posts, ring-beams and wattle walls.

The process of gathering, assembling and maintaining these materials required huge amounts of effort, teamwork and determination. Archaeologists estimate that approximately 100 people lived and worked in a self-supporting community, producing their own food, clothes, equipment, tools and weapons. The site was occupied from the fifth to the second or first century BC.

For some unknown reason, Castell Henllys was abandoned in the late Iron Age. The site may have been occupied in later centuries by Irish settlers, but it fell into obscurity and became overgrown until it was surveyed on a late-eighteenth-century estate map. In 1992, the site was bought by the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, which has since supported an extensive education programme and long-term experimental archaeology project.

In 2001, a group of seventeen volunteers (including three children) agreed to participate in a reality TV show, Surviving the Iron Age, in which cameras followed their attempts to live together at Castell Henllys for seven weeks. While the BBC dubbed the series ‘an experiment in living history’, one of the participants described the experience as ‘hell on earth’. Unfortunately, the filming took place during one of the wettest autumns since records began. The incessant rain made life very uncomfortable in the absence of a change of clothing and modern-day essentials such as toilet paper, deodorant and soap. Two of the children, aged 4 and 5, were withdrawn from the experiment by their mother after the youngest fell ill with food poisoning. Another participant withdrew after catching a bug.

Such experimental archaeology illustrates how surviving the Iron Age was no walk in the park. What became clear to the participants was that survival depended upon meeting the basic needs of shelter, food and water, but in ways that required a lot of collaboration, resilience and hard work. We take for granted turning a tap on to fill a kettle and fetching water from a nearby stream proved too much for the time travellers, who were frustrated by leaking buckets. This happened even though the producers provided a modern-day water tap. The daily grind of menial tasks took its toll within the group and friction soon developed. The humble wellington boot became a prized possession which they could not give up: it was a symbol of how far the twenty-first century had intervened in this living history project.

Water supply was a key factor in the location of hillforts. It is estimated that on the basis of the average person needing 2 litres of water a day to keep going, a hillfort of 100 people would require 44 gallons simply for drinking, let alone cooking. If animals were accommodated on site, then the water demands could be much higher. For these reasons, most hillforts were located near rivers or streams, although water may also have been obtained by catching rainwater, or from springs or wells.

Clegyr Boia hillfort (near St Davids), has two wells nearby: Ffynnon Dunawd and Ffynnon Llygaid. According to myth, the former is allegedly named after a young girl, Dunawd, who had her throat slit by her stepmother. The fountain sprang from where the blood was spilled. Ffynnon Llygaid, on the south side of Clegyr Boia, was reputed to clear eye problems.

For the Celts, the central hearth or fireplace was the basis for cooking food, boiling water, heating the roundhouse and the focal point around which they talked – interestingly, the Latin word ‘focus’ means fireplace. The Welsh word ‘aelwyd’ goes beyond hearth to convey the notion of family, or kinship, and home. The roundhouse image of cooking pots hanging from ceiling timbers over a central fire, with the family sharing stories, reinforces the social element of the hearth. The fire gave warmth while the rising smoke seeped through the thatched roof (rather than a distinct hole), keeping it dry and free from insects. The Roman historian Diodorus Siculus noted that the custom of the Celts was to sleep on wild animal skins on the ground ‘and to wallow among bed-fellows on either side’. Findings from Danesbury and other camps in the south of England suggest that larger roundhouses may also have accommodated various animals, including dogs and cats as pets or for pest control.

Radiocarbon dating shows that some of the Pembrokeshire hillforts are a few hundred years older than was once thought, and actually predate the Iron Age. Archaeologists have worked painstakingly in their reconstruction of the Castell Henllys roundhouses, but it is important to remember that these are modern representations. For example, the walls were painted with lime wash for the purpose of improving visibility for modern...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.7.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Sonstiges ► Geschenkbücher | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | caldey • coastal path • Fishguard • haverfordwest • little book of pembroke • little history of pembrokeshire • little pembrokeshire • Milford Haven • narbeth • Newport • neyland • pembroke dock • Pembrokeshire Coast National Park • pembrokeshire national park • preseli Hills • saundesfoot • Skomer • smallest city • St Davids • Tenby |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-391-X / 180399391X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-391-1 / 9781803993911 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich