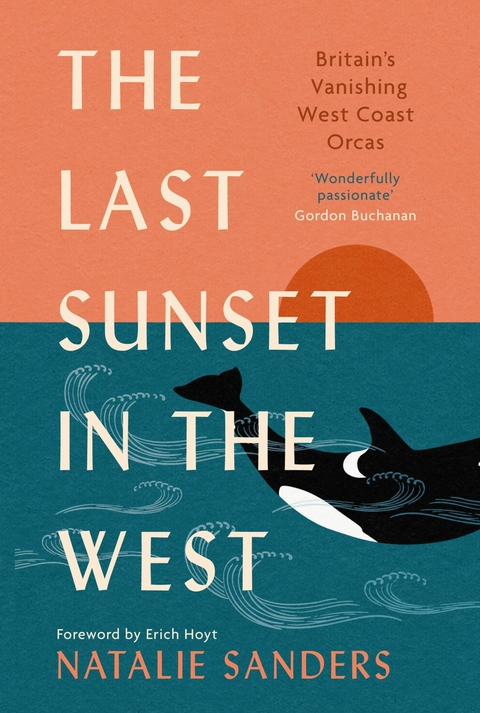

The Last Sunset in the West (eBook)

320 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-1-78885-721-5 (ISBN)

Having completed her PhD in marine biology, Natalie Sanders now works as a marine consultant and has collaborated with the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust and charities in British Columbia, Canada. She lives in south-west England with her husband and two children.

Having completed her PhD in marine biology, Natalie Sanders now works as a marine consultant and has collaborated with the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust and charities in British Columbia, Canada. She lives in south-west England with her husband and two children.

Introduction

THE ORCA IS THE OCEAN’S APEX PREDATOR and most sentient inhabitant, an animal that has since time immemorial fascinated, scared, intrigued and inspired humankind. It has been given many names, but the most common are orca and killer whale. As the largest member of the dolphin family, orcas are not actually whales at all, but it is commonplace to refer to them as such. Regional names are also used such as the Gaelic mada-chuain, which is how they are known in the Hebrides.

‘Blackfish’ and ‘kakawin’ are commonly used in the Pacific Northwest by local and indigenous cultures. While researchers, who love and respect them, most commonly use ‘killer whale’, this is increasingly viewed as pejorative and there is a public desire to move away from it. The term ‘killer whale’ came from Spanish sailors who saw them hunting larger whales in groups. They called them asesina ballenas, meaning ‘whale killers’ but, somewhere along the line, noun and adjective were switched to become ‘killer whale’.

Their scientific, Latin, name is Orcinus orca, where Orcinus translates as ‘The kingdom of the dead’ and orca as ‘a kind of whale’, which conjures up unfortunate images of them as deadly ferocious, heartless creatures who kill for pleasure. Having spent many years learning about them, observing them in the wild and analysing countless hours of drone footage, there is no denying their hunting prowess, but they are so much more complex. I have found them to be compassionate, altruistic, intelligent, playful and capable of an emotional depth that rivals our own. Therefore, in this book, I refer to them simply as orcas. Who are we to judge them on the basis of their hunting techniques when we, as humans, are capable of so much worse?

Orcas are found all over the world, in every single ocean, some fifty thousand individuals who range from the tropics to the poles, but it is the frigid, fertile waters of the northern and southern hemisphere’s high latitudes that they are particularly fond of. Some populations spend their entire lives offshore, while some roam huge stretches of coastline in search of their prey and others prefer to stick to the same location throughout their lives.

The British Isles are blessed with a truly spectacular abundance of marine life. In spring and summer, the seas are rich with plankton blooms that support a huge number of fish, including sharks, and marine mammals such as seals, dolphins and even large whales like minke, humpback and the occasional sperm whale. It is not well known for its populations of orcas, but we are lucky enough to experience plenty of sightings every year.

An increasing number of sightings occur around Orkney and Shetland, in the north and occasionally on the east coasts of Scotland too. These are predominantly of a community known as the Northern Isles Community. Your best bet for seeing orcas is in July or November in Shetland, but there is a chance you could see them in any other month. We also get our ‘Viking visitors’ or migratory orcas from Iceland, who are predominantly fish eaters but, every summer, some come over to feast on seal pups. About 30 or so individuals are known to split their time between Iceland and Shetland and Orkney, depending on what food they are eating. This represents only a very small fraction of the Icelandic population, and it isn’t really known why only a handful make the journey. You are only likely to see them for a couple of months in the summer.

However, there is a small group of orcas present in the British Isles and Ireland who are referred to as our only resident pod and they can be seen throughout the year, predominantly on the rugged and wet west coast of Scotland, in the Hebrides.

Some argue that the Northern Isles Community should now be considered semi-resident or even resident in UK waters, but it is the West Coast Community that has long been considered our only resident pod. Sometimes seen in Ireland, Wales and even England, it is the Hebrides that is their main home.

For those who do not know, the Hebrides is a long archipelago of Atlantic islands off the west coast of Scotland that formed some 525 million years ago in the Precambrian period. This landscape was formed by the ice ages and the great cycles of thaw and freeze. Evidence of its long history is all around, from rocks and boulders which have become polished and smooth through the ebb and flow of tides over millennia to the more recent 4,000-year-old peat bogs that cover much of the landscape. Split into two main groups, the Inner and Outer Hebrides are separated by the Minch in the north and the Sea of the Hebrides in the south. Seventy-nine islands comprise the Inner Hebrides, thirty-five of which are inhabited, including the Isles of Mull, Jura, Skye and Rum. The Outer Hebrides, while separated by only a small sea, seem to be a world away, with their own distinctive language, culture and deeply held religious views. They consist of some fifty substantial islands, with many smaller islands jotted among them. In the inhabited islands of the Outer Hebrides, or Na h-Eileanan an Iar, Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken even after centuries of decline.

Although the Hebrides lie fairly far north at Latitude 57, the same latitude as parts of Sweden, Russia, Alaska and Quebec, they experience a relatively mild climate thanks to the Gulf Stream. Some of the best beaches in the world can be found here, with crystal-clear blue waters, golden sandy beaches and beautiful sand dunes. Just behind the sand dunes, the fringes of the coastline are covered by machair, the Gaelic word for the low-lying fertile land that is a characteristic habitat of the Outer Hebrides. If you were to see a picture of the Isle of Harris on a sunny day you could easily mistake it for the Caribbean – an illusion that would quickly end the moment you dipped your toe into the cold waters.

The population of orcas that call the Hebrides home are known as the West Coast Community (WCC). This group has been delighting scientists and whale enthusiasts for years, but we still know remarkably little about them. They spend their days milling around the sparsely populated Inner and Outer Hebridean Islands, in an area of outstanding natural beauty but also where there is some of the harshest weather in the British Isles. These are, at best, only eight members left – four males and four females. Not long ago there were ten, and stories abound of more along with calves back in the 1980s, but no one really knows if the group was once more prolific. Since 2016, only two of the males have been sighted, raising concerns that they may be the only two remaining.

Tracking them down is no easy feat, making their lives something of a mystery. What we do know is largely down to citizen science where members of the public, from diehard orca fans to lucky ferry passengers who chance upon a sighting submit details and photographs to the Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust (HWDT), a small but effective charity located in Tobermory on the Isle of Mull. Since their establishment in 1994, they have been collecting sightings, gathering information and running research expeditions to learn about the marine life of the Hebrides – not just orcas, but fifteen other species and counting. They have generated the largest coherent dataset of its kind in the UK, evidence which has been used to establish new marine protected areas, guide fisheries in adopting safer fishing practices, run educational programmes across the Hebrides and help understand the specific challenges marine life faces in this most beautiful place.

They promote mindful engagement with nature and have created the Hebridean Whale Trail, which includes over thirty sites across the west coast and Hebrides where you can watch whales and dolphins from land with little to no impact on marine life. At each site volunteers engage with and educate visitors, and sightings are added to their Whale Track app. It is their work and local connections that have made HWDT the success that it is.

From citizen-science sightings like these, and research expedition data, we can piece together where the West Coast Community is seen, who they are seen with, where they have been travelling to and from, how old its members might be and more besides. It is thanks to the people who help with sightings that we know as much as we do.

The West Coast Community has been hitting the headlines in recent years, grabbing the attention of the world. They have been featured on The One Show on the BBC, in countless national and local newspapers and even the US Smithsonian. Sadly, the orcas’ turn in the media spotlight in 2016 arrived with the heartbreaking discovery of one of their number stranded on a beach after getting entangled in fishing gear. Losing this individual brought the population one step closer to extinction and, with that, their plight became of interest around the world.

My journey to writing this book began in 2014 when I travelled to the Hebrides to join a research expedition on the Silurian, the research vessel belonging to the HWDT. Built in 1981 in Seattle, she is a 61ft Skoochum one ketch, meaning she has two masts for the sails, although her motor is used more often than not to keep her speed and direction constant. She has had quite a life, having been impounded for smuggling cocaine from Colombia into Florida.

Redeeming her from this criminal past, she was used by the BBC in filming the landmark series The Blue Planet. The ‘first ever comprehensive series on the natural history of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie |

| Naturwissenschaften | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Aquarius • British Wildlife • Bull Orca • climate change • climate crisis • conservation • cop26 • cop29 • Extinction crisis • fully revised • John Coe • killer whales • Marine Biology • marine line • Maritime History • Natural History • nature and animals • nature conservation • Nature writing • North Sea Animals • Ocean Life • Orcas • sandstone • updated edition • Up to date information • Vancouver Island • West Coast Orca • Whales |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-721-6 / 1788857216 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-721-5 / 9781788857215 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich