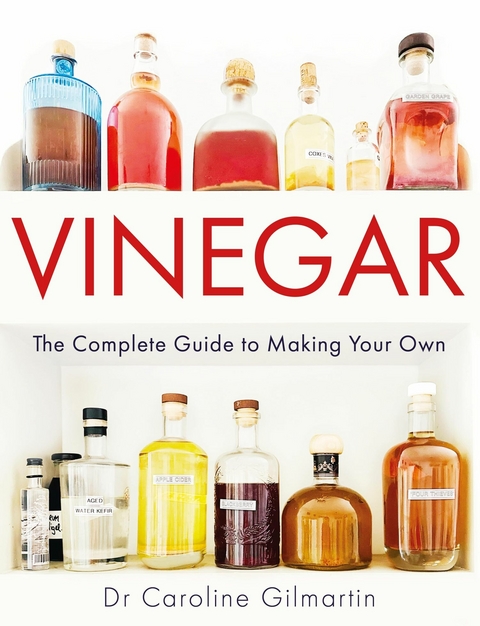

Vinegar (eBook)

176 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4367-9 (ISBN)

Dr CAROLINE GILMARTIN is a fermentation specialist with a background in microbial genetics and an interest in the relationships between fermentation, diet, and gut health. Having recently retired from full-time fermented food production, she is an advisory board member for the Fermenters Guild. Through her Bristol-based company Every Good Thing she sells cultures and teaches fermentation techniques.

CHAPTER 2

A POTTED VINEGAR HISTORY

It would be remiss of me to gloss over vinegar’s fascinating history, as the processes we will be using have developed over thousands of years – so here is a whistlestop tour. There are two tales here: first, how the relationship between yeasts and AAB arose; and then the human perspective – how vinegar became so integral to our lives that we completely take it for granted.

MICROBES AND VINEGAR

Vinegar microbes have a long history of symbiotic association; you can see this in action as a mother of vinegar forms on the surface of a freshly made batch. This is a type of biofilm formed by a mass of microbes growing together within a cellulose matrix, similar in principle to a kombucha SCOBY or kefir grains. These are fascinating manifestations; bacteria and yeasts themselves can’t be seen without a microscope, yet they can produce these tangible and very visible entities.

Prokaryotes, including anaerobic bacteria, developed about 3.5 billion years ago. The evolution of Cyanobacteria, which could photosynthesise and produce oxygen, led gradually to the presence of aerobic bacteria, such as AAB, around 3.1 billion years ago (according to a new genetic analysis of dozens of families of microbes).5

Symbiotic relationships exist in other fermented foods: kombucha, water kefir, milk kefir and mother of vinegar are all examples of biofilms.

More complex, single-cellular yeasts (eukaryotes) developed about 2.7 billion years ago through endosymbiosis, whereupon smaller microbes became incorporated into larger ones. After the appearance of fruiting bodies of plants, about 125 million years ago, yeasts developed the ability to rapidly convert simple sugars into ethanol. This gave them a selective advantage because ethanol is toxic to many microbes, but yeasts can tolerate quite high levels. Over time, yeast ethanol metabolism and AAB use of alcohol as an energy source became aligned. Today both AAB and yeasts are ubiquitous in nature, on and in plant surfaces, soil and air.

HUMANS AND VINEGAR

While much is known about the origins of alcohol production, it is harder to pinpoint exactly when vinegar ‘began’. At first people didn’t know how to stop wine from turning into vinegar, and in many instances there might not have been much difference between the two – it’s fair to say that ancient wines would have been rather challenging for our palates.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania discovered 9,000-year-old Neolithic jars at Jiahu (Henan province, China) in which were detected traces of the earliest known alcoholic beverage. It appears to have been a delicious sounding mixture of wild grapes, hawthorn berries, rice and honey. Remnants of early wine manufacture are also scattered throughout the Middle East, but it’s not clear who, if anyone, can claim the rights to the ‘invention’ of vinegar.

Alcohol traces were found in fragments of jars from the neolithic period. ADOBE STOCK

The earliest known wines: a delicious-sounding mixture of wild grapes, hawthorn berries, rice and honey.

Vinegar Over the Ages

The Babylonians

The first written record of vinegar has been identified as dating from Babylonian times. By 3000bc, Babylonian civilisation was well established, and the deciphering of cuneiform symbols inscribed upon clay tablets tells us that they were great innovators, with winemaking an important industry.

Although vines were grown, dates grew better, so date beer/wine was the mainstay. The Babylonians knew that vinegar was able to prevent the deterioration of foodstuffs, and it was extensively used in preservation (more so than as a seasoning). Preservation was an activity that occupied much of our forebears’ time, as the seasonality of produce meant that storage was of paramount importance. As soured date-beer vinegar was abundant, it was more economical than using salt (see page 129 to find out how to make your own date or raisin vinegar). As viticulture spread throughout the Mediterranean, so did the presence of vinegar.

The Romans

In Roman times, diluted vinegar known as ‘posca’ was the drink of slaves and soldiers. It was safer than drinking plain water as the effect of vinegar in terms of water purification was known, even if the agents of disease were not – and one supposes that it made for a sober workforce and army too!

An acetabulum was found at every Roman feast (Museum August Kestner, Hannover). MARCUS CYRON

It was common in Roman households to have a vinegar-containing dish called an acetabulum on the table at mealtimes. As we know, the Romans were great feasters, and between courses it was usual to dip bread into it and consume this as a palate cleanser. This is interesting, given what we have recently learned about the ability of vinegar to help regulate glucose levels (see page 156).

Lucius Columella, who lived during the first century, in his text De Re Rustica (Farming Topics), presents the very first written recipes for the use of vinegar both in the kitchen and as a medicine (see page 126 for Columella’s fig vinegar recipe, which you can try yourself).

Rather unfortunately for them, the Romans also developed sapa, a delicacy of sweetened, boiled grape syrup. This they prepared by boiling fermented grape must in lead pots. Acetic acid in the must reacted with the pots, causing high concentrations of lead acetate in the sapa, and consequently, lead poisoning among the aristocracy.

An example of cuneiform tablets that were deciphered to reveal the first written mention of vinegar – sadly not the exact ones. WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Romans even had a verb for the act of boiling down grape must into a syrup: defrutare. It is likely that this tradition of boiling must eventually developed into the production of balsamic vinegar (see page 138).

The Ancient Greeks

The ancient Greeks had their own, far more beneficial version of a vinegar beverage. Oxymels were comprised of water, vinegar, honey and herbs. The physician Hippocrates, also known as ‘the father of modern medicine’, prescribed oxymels as salves for wounds and sores, and to be imbibed for the treatment of respiratory diseases. The Greek scholar Theophrastus (371–287bc6) described how vinegar reacted with metals to make mineral pigments such as white lead and verdigris from copper, for artistic use.

A paintbox with mineral pigments; vinegar was reacted with metals to make them. DADEROT

Ancient Islamic Civilisation

By ad700, the use of vinegar in ancient Islamic civilisation was also well established. The prophet Mohammed said: ‘Allah has put blessings in vinegar, for truly it was the seasoning used by the prophets before me.’ Although alcohol is considered haram, or forbidden according to the laws of Islam, vinegar is halal, or permitted.

This put a different perspective upon its production, because while the alcoholic starting material, most likely date beer, would have been without value, the opposite was true of vinegar. A one-step process was used for production, whereby fruit juice was given optimal conditions to turn to vinegar via simultaneous development of alcohol and acetic acid. (See page 125 for how to set up all-in-one vinegars.)

Europe

By the end of the fourteenth century, vinegar was firmly on the map as a genuine industry, centred in Orléans, France. This had grown hand-in-hand with the development of the French wine industry: the aristocracy had developed a taste for the fine wines of the Bordeaux, Loire and Rhône regions, most of which were barrelled and then transferred to barges that travelled up the River Loire to Orléans, the nearest major river port to Paris, for distribution via local wine merchants.7

Boats transported wine barrels along the Loire to Orléans where they were checked before leaving for Paris – taxes were payable, and no one wanted to pay taxes for undrinkable wine. ALAIN DARLES

The range of vinegars available from Martin Pouret, the last traditional vinegar maker in Orléans. MARTIN POURET

Once unloaded, the wine would be inspected by a team of piquers-jureurs, or quality control inspectors. Anything failing to make the grade was sold to local vinegar and mustard makers: vinegar was in high demand as a food preservative. With Orléans as a hub for over-oxidised fine wines, these became the bases for similarly fine vinegar. The process used was to lie aerated barrels on their sides to age for several months; this became known as the ‘Orléans method’, and is still used today. Orléans vinegar maintained its reputation until the French Revolution, whereafter industrialisation, and the use of cheap distilled spirits and global competition, caused its demise. From 300 producers pre-Revolution, today just one of the original vinaigriers, Maison Martin Pouret, survives.

Across the pond in the UK, in 1845 there were 65 London-based vinegar makers, using products including raisins, beer, gin and wood as bases for vinegar production. These days, big names including Sarson’s, Aspall and Manor Vinegar produce much of the regular malt and distilled fare, although there has been an upsurge in the production of raw...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Gesunde Küche / Schlanke Küche |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Essen / Trinken ► Themenkochbücher | |

| Schlagworte | acetic acid • acetification • acidity • alcohol base • balsamic vinegar • Contamination • Creativity • Culture • Distillation • Fermenters Guild • fermenting • Flavour • homemade • Hydrometer • infused vinegar • Kombucha • malt vinegar • microbes • pH • pickling • preservatives • scrap vinegar • spirit vinegar • sulphites • Titration • Vessel • Vinegar • vinegar mother • wine vinegars • yeast |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4367-7 / 0719843677 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4367-9 / 9780719843679 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 36,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich