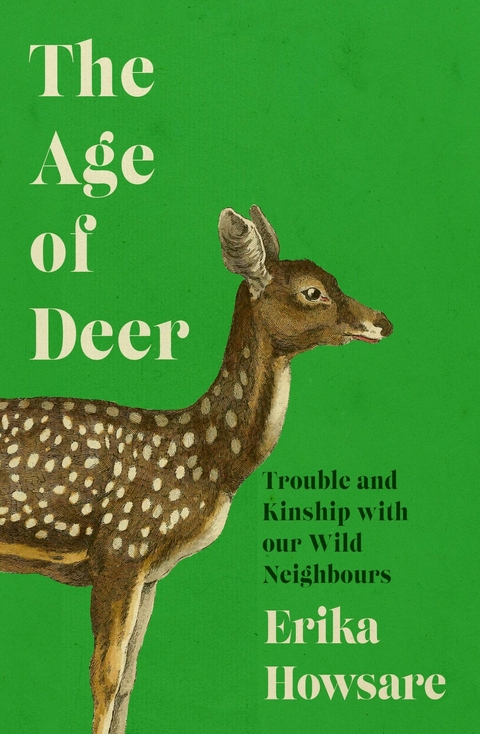

The Age of Deer (eBook)

208 Seiten

Icon Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78578-948-9 (ISBN)

Erika Howsare is a writer, journalist and teacher. Her essays, reviews and interviews have appeared in publications such as the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Rumpus, and she is the author of two collections of poetry, How is Travel a Folded Form? and FILL: A Collection (with Kate Schapira). She lives in the Blue Ridge in central Virginia.

Erika Howsare is a writer, journalist and teacher. Her essays, reviews and interviews have appeared in publications such as the Los Angeles Review of Books and The Rumpus, and she is the author of two collections of poetry, How is Travel a Folded Form? and FILL: A Collection (with Kate Schapira). She lives in the Blue Ridge in central Virginia.

CHAPTER 1

Dancing

IT WAS THE NIGHT OF WINTER SOLSTICE, AND HERE WERE all the trappings of a school play: music stands, metal risers, handmade banners. The battered stage was hung with garlands of evergreen. My family and I, among several hundred others, sat with our coats draped over the backs of our plastic chairs.

Two mothers whispered—“Oh, is that Evelyn?”—“Yes.” A baby coughed.

Christmas would barrel over us in just a few days, but there were no mangers or Magi here. This was the annual winter play presented by a small private school near my home. We’d come again that year to soak up its bohemian patchwork of song and chant: pagan Yule traditions, solstice rituals, and medieval Christmas overtones. Kids were dressed as aproned villagers, as avatars of the four elements, as Saint George and Father Christmas, and as Holly and Ivy, the beloved evergreen leaves of winter.

In the audience, I spotted a woman I know and nodded to her. She leaned against the wall, wearing deer antlers on her head and a long cloak of dark green, like a hemlock forest at dusk.

Some elements of the performance change from year to year, but the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance stays the same. Abbots Bromley is a village in the West Midlands of England, and the program hinted that the dance originated there nearly a thousand years ago. As the first notes of the tune cut through the murmur and movement of the audience and seven dancers entered in a stately single file, the Horn Dance did carry an unmistakable sense of antiquity. It had the feel of an artifact older than the red cross on Saint George’s breastplate. This dance felt almost prehistoric, and it was the antlers the kids held to their heads that made it so.

The music was a halting, minor-key tune played on recorder by a lone eighth grader at the corner of the stage. The antlered dancers wore plain tunics, the color of deerskin. The choreography was very simple: The dancers slowly crossed the stage, pausing to lift a foot behind them every few paces, the toe pointing backward just like a deer’s hoof when it strolls through grass. Some of the girls’ legs were nearly that slender.

A dignified melody, almost a dirge. The dancers formed two lines and approached each other, then retreated and bowed; the lines interlaced. In a diagonal across the stage, they arranged themselves by height and by antler size: the old obsession with status, manifested in bone.

In Abbots Bromley, the dance is one of a number of traditional European “hoodening rituals,” in which people once donned animal skins or heads, dancing or marching to ensure a successful hunt. As far back as the fourth century, Saint Augustine is said to have condemned these practices and called them “filthy,” both their antiquity and their pagan power seen as threats by the ascendant church.

Gradually, as the dancers and the tune looped around on themselves, the audience settled into a hypnotic hush. If a shabby auditorium in Virginia was not the Horn Dance’s native habitat, it carried power nonetheless, even when its vehicles were nervous middle-schoolers. That naked, shaky music felt to me like the struggle of any human, striving within a matrix—family, community—and these ritualized movements conveyed a common need for the good luck of sustenance.

Here in Virginia, the deer season was mostly behind us. Some people in the room had killed does or bucks that fall. Some would go home to venison backstrap in their freezers, venison stew in Crock-Pots on their counters, racks of antlers on their walls or porches. Some may have given meat to hungry neighbors. Surely there are households in this county where people pray to kill deer in the fall, so that throughout the winter they’ll have enough to eat.

When Europeans encountered Indigenous people on the edges of North America, they must have understood the importance of deer to the Native population. Such a connection was part of their own cultural foundation, too. Throughout much of what would come to be called the Old World, people had lived with and made use of deer for generations.

Across cultures, deer are frequent actors in stories and myths. But in truth, our intimate involvement with deer is older than any of these artifacts. We’ve been bound by mysterious ties since before any story we remember.

Deer keep company with some of the oldest human graves in the world. A tomb found in Qafzeh Cave—a rock shelter in the Yizrael Valley in Israel—contains the bones of at least twenty-seven people, which have rested on this rock ledge for nearly a hundred thousand years’ worth of days and nights. The people lie among hearths and various animal remains, including red and fallow deer. Archaeologists point to ornamentation with ocher and seashells as evidence that these were deliberate human burials.

The people at Qafzeh did another remarkable thing: They seem to have spent many years caring for a child with a terrible brain injury. After a blow to the head around age five, the child, known as Qafzeh 11, would likely have suffered “significant neurological and psychological disorders, including troubles in social communication,” yet lived until age twelve or thirteen. After death, he or she was laid supine into a pit, in a ceremonial burial that apparently indicates “a unique case of differential treatment”—extra honor, as it were, as though to make up for such a compromised existence. It’s a pair of deer antlers that signals this distinction. They’re held in the child’s folded hands, near the face.

Antlers keep company with other prehistoric remains, too, ornamenting hearths, or forming beds or roofs inside tombs.

We can only speculate on what such offerings meant at the time, but we do know that more recent mythologies cast deer as psychopomps: escorts to the afterlife, a part of nature that breaks off to soften nature’s deadly force. It’s a wish for someone to take care of us on the journey to the hereafter—to oversee us, forgive us, keep us company. Vikings, for example, believed that a deer with oaken antlers, called Eikthyrnir, wandered Valhalla and accompanied fallen heroes on the journey across the river to the land of the dead. The stag’s antlers dripped water into a spring that fed all the rivers of the world: a connection between deer, water, and renewal that infuses many myths.

I once saw a reference to deerskin burial shrouds, too. Certainly this idea exists in legends—like in the Chansons de Roland, when Charlemagne has the bodies of Roland and two other heroes prepared for burial: “The barons’ bodies they then take up and wind / Straitly in shrouds made of the roebuck’s hide.”

It’s a tantalizing idea, that people wrapped the dead in soft, warm skins as they laid them into the earth. Something about it is tremendously comforting.

There’s an old Siberian-Turkish story about a hunter who reconstructs the skeleton of a deer he’s just killed, substituting a piece of wood for the rib his arrow had broken. Later, he kills a different deer and discovers the wooden rib inside its body.

Hunters in both Eurasia and the Americas felt bound to treat their quarry as a respected interlocutor, a sort of dance partner in the ritual of survival. A deer was not just a target, but a conscious being who participated in the event of its own demise. Though its meat would transmute into human life, bones were the undestroyed basis by which deer life, in a larger sense, could continue. To carefully lay out a deer’s skeleton after cleaning and butchering its body was a gesture of honor and atonement. In turn, one became one’s prey. In some places, eating venison was thought to make one swift and wise; in others, it was said to breed timidity.

Some cultures propose a single, eternal figure who represents all deer: Awi Usdi is a white deer who oversees Cherokee hunters, making sure that each slaughtered deer is properly asked for forgiveness. If a hunter neglects the ritual, Awi Usdi will cripple that person with rheumatism.

Different groups made different rules for hunters. Some banned boastful talk; others made it taboo for hunters to cook or consume certain parts of a deer, like stomachs and tongues, or to hunt while one’s wife was pregnant. Before the hunt, hunters around the globe might dress in deerskins or make deer sounds. In North America, hunters purified themselves in steam or with special elixirs, called or sang out to their prey, and set off on the hunt carrying charms sewn into deerskin pouches: crystals, pigments, or the foot of a fawn.

Even the stags galloping across the walls of Paleolithic cave art sites have been understood this way—as an address to the animal other. In Europe’s most significant cave galleries, Lascaux, Chauvet, and Altamira, deer are one of the four most frequently depicted subjects.

We are still finding more ancient deer on the rocks. In 2003, archaeologists discovered more than twenty figures inside a cave called Church Hole, one of many caves in a limestone gorge in England named Creswell Crags. The images are the first Ice Age art identified in Britain; they are engraved, not painted, which helped them go unnoticed even during many decades of excavating the cave floor.

“We know that Neanderthals were here, fifty thousand years ago,” said the paleontologist Angharad Jones as we crossed a tiny bridge and followed a path into the gorge. To one side, a group of schoolkids were throwing spears at a rubber bison. Jones, tall and elegant in a trench coat, had already shown...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.1.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Naturführer | |

| Naturwissenschaften | |

| Technik | |

| Schlagworte | Annie Proulx • Benedict Macdonald • Charles Smith-Jones • Dave Goulson • Deer of the World • Guy Shrubsole • Helen Macdonald • H is for Hawk • JA Baker • landmarks • Lee Schofield • Nan Shepherd • Neil McIntyre • Otherlands • Robert Macfarlane • roger deakin • Steve Brusatte • The Goshawk • The Old Ways • The Peregrine • The Rise and Reign of the Mammals • Thomas Halliday • TH White • Underland |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78578-948-1 / 1785789481 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78578-948-9 / 9781785789489 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 840 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich