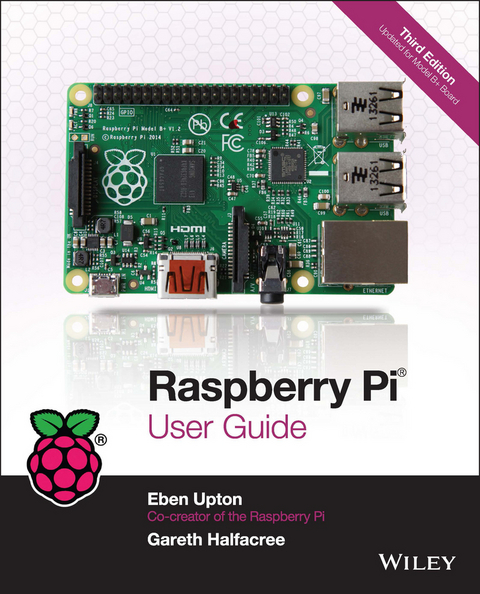

Raspberry Pi User Guide (eBook)

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-118-92167-8 (ISBN)

The “unofficial official” guide to the Raspberry Pi, complete with creator insight

Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rdEdition contains everything you need to know to get up and running with Raspberry Pi. This book is the go-to guide for Noobs who want to dive right in. This updated third edition covers the model B+ Raspberry Pi and its software, additional USB ports, and changes to the GPIO, including new information on Arduino and Minecraft on the Pi. You’ll find clear, step-by-step instruction for everything from software installation and configuration to customizing your Raspberry Pi with capability-expanding add-ons. Learn the basic Linux SysAdmin and flexible programming languages that allow you to make your Pi into whatever you want it to be.

The Raspberry Pi was created by the UK Non-profit Raspberry Pi Foundation to help get kids interested in programming. Affordable, portable, and utterly adorable, the Pi exceeded all expectations, introducing millions of people to programming since its creation. The Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rd Edition helps you and your Pi get acquainted, with clear instruction in easy to understand language.

- Install software, configure, and connect your Raspberry Pi to other devices

- Master basic Linux System Admin to better understand nomenclature and conventions

- Write basic productivity and multimedia programs in Scratch and Python

- Extend capabilities with add-ons like Gertboard, Arduino, and more

The Raspberry Pi has become a full-fledged phenomenon, popular with tinkerers, hackers, experimenters, and inventors. If you want to get started but aren’t sure where to begin, Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rd Edition contains everything you need.

The unofficial official guide to the Raspberry Pi, complete with creator insight Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rdEdition contains everything you need to know to get up and running with Raspberry Pi. This book is the go-to guide for Noobs who want to dive right in. This updated third edition covers the model B+ Raspberry Pi and its software, additional USB ports, and changes to the GPIO, including new information on Arduino and Minecraft on the Pi. You ll find clear, step-by-step instruction for everything from software installation and configuration to customizing your Raspberry Pi with capability-expanding add-ons. Learn the basic Linux SysAdmin and flexible programming languages that allow you to make your Pi into whatever you want it to be. The Raspberry Pi was created by the UK Non-profit Raspberry Pi Foundation to help get kids interested in programming. Affordable, portable, and utterly adorable, the Pi exceeded all expectations, introducing millions of people to programming since its creation. The Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rd Edition helps you and your Pi get acquainted, with clear instruction in easy to understand language. Install software, configure, and connect your Raspberry Pi to other devices Master basic Linux System Admin to better understand nomenclature and conventions Write basic productivity and multimedia programs in Scratch and Python Extend capabilities with add-ons like Gertboard, Arduino, and more The Raspberry Pi has become a full-fledged phenomenon, popular with tinkerers, hackers, experimenters, and inventors. If you want to get started but aren t sure where to begin, Raspberry Pi User Guide, 3rd Edition contains everything you need.

Eben Upton is a founder of the Raspberry Pi Foundation and serves as the CEO of Raspberry Pi (Trading), its commercial arm. In an earlier life he founded two mobile games companies and was Director of Studies for Computer Science at St John's College, Cambridge. He holds a BA, a PhD and an MBA from the University of Cambridge. Gareth Halfacree is a freelance technology journalist and the co-author of the Raspberry Pi User Guide alongside project co-founder Eben Upton. Gareth can often be seen reviewing, documenting or even contributing to projects, including GNU/Linux, LibreOffice, Fritzing and Arduino.

Introduction

“CHILDREN TODAY ARE digital natives”, said a man I got talking to at a fireworks party. “I don’t understand why you’re making this thing. My kids know more about setting up our PC than I do.”

I asked him if they could program, to which he replied: “Why would they want to? The computers do all the stuff they need for them already, don’t they? Isn’t that the point?”

As it happens, plenty of kids today aren’t digital natives. We have yet to meet any of these imagined wild digital children, swinging from ropes of twisted-pair cable and chanting war songs in nicely parsed Python. In the Raspberry Pi Foundation’s educational outreach work, we do meet a lot of kids whose entire interaction with technology is limited to closed platforms with graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that they use to play movies, do a spot of word-processed homework and play games. They can browse the web, upload pictures and video, and even design web pages. (They’re often better at setting the satellite TV box than Mum or Dad, too.) It’s a useful toolset, but it’s shockingly incomplete, and in a country where 20 percent of households still don’t have a computer in the home, even this toolset is not available to all children.

Despite the most fervent wishes of my new acquaintance at the fireworks party, computers don’t program themselves. We need an industry full of skilled engineers to keep technology moving forward, and we need young people to be taking those jobs to fill the pipeline as older engineers retire and leave the industry. But there’s much more to teaching a skill like programmatic thinking than breeding a new generation of coders and hardware hackers. Being able to structure your creative thoughts and tasks in complex, non-linear ways is a learned talent, and one that has huge benefits for everyone who acquires it, from historians to designers, lawyers and chemists.

Programming Is Fun!

It’s enormous, rewarding, creative fun. You can create gorgeous intricacies, as well as (much more gorgeous, in my opinion) clever, devastatingly quick and deceptively simple-looking routes through, under and over obstacles. You can make stuff that’ll have other people looking on jealously, and that’ll make you feel wonderfully smug all afternoon. In my day job, where I design the sort of silicon chips that we use in the Raspberry Pi as a processor and work on the low-level software that runs on them, I basically get paid to sit around all day playing. What could be better than equipping people to be able to spend a lifetime doing that?

It’s not even as if we’re coming from a position where children don’t want to get involved in the computer industry. A big kick up the backside came a few years ago, when we were moving quite slowly on the Raspberry Pi project. All the development work on Raspberry Pi was done in the spare evenings and weekends of the Foundation’s trustees and volunteers—we’re a charity, so the trustees aren’t paid by the Foundation, and we all have full-time jobs to pay the bills. This meant that, occasionally, motivation was hard to come by when all I wanted to do in the evening was slump in front of the Arrested Development boxed set with a glass of wine. One evening, when not slumping, I was talking to a neighbour’s nephew about the subjects he was taking for his General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE, the British system of public examinations taken in various subjects from the age of about 16), and I asked him what he wanted to do for a living later on.

“I want to write computer games”, he said.

“Awesome. What sort of computer do you have at home? I’ve got some programming books you might be interested in.”

“A Wii and an Xbox.”

On talking with him a bit more, it became clear that this perfectly smart kid had never done any real programming at all; that there wasn’t any machine that he could program in the house; and that his information and communication technology (ICT) classes—where he shared a computer and was taught about web page design, using spreadsheets and word processing—hadn’t really equipped him to use a computer even in the barest sense. But computer games were a passion for him (and there’s nothing peculiar about wanting to work on something you’re passionate about). So that was what he was hoping the GCSE subjects he’d chosen would enable him to do. He certainly had the artistic skills that the games industry looks for, and his maths and science marks weren’t bad. But his schooling had skirted around any programming—there were no Computing options on his syllabus, just more of the same ICT classes, with its emphasis on end users rather than programming. And his home interactions with computing meant that he stood a vanishingly small chance of acquiring the skills he needed in order to do what he really wanted to do with his life.

This is the sort of situation I want to see the back of, where potential and enthusiasm is squandered to no purpose. Now, obviously, I’m not monomaniacal enough to imagine that simply making the Raspberry Pi is enough to effect all the changes that are needed. But I do believe that it can act as a catalyst. We’re already seeing big changes in the UK schools’ curriculum, where Computing is arriving on the syllabus this year and ICT is being entirely reshaped, and we’ve seen a massive change in awareness of a gap in our educational and cultural provision for kids just in the short time since the Raspberry Pi was launched.

Too many of the computing devices a child will interact with daily are so locked down that they can’t be used creatively as a tool—even though computing is a creative subject. Try using your iPhone to act as the brains of a robot, or getting your PS3 to play a game you’ve written. Sure, you can program the home PC, but there are significant barriers in doing that which a lot of children don’t overcome: the need to download special software, and having the sort of parents who aren’t worried about you breaking something that they don’t know how to fix. And plenty of kids aren’t even aware that doing such a thing as programming the home PC is possible. They think of the PC as a machine with nice clicky icons that give you an easy way to do the things you need to do so you don’t need to think much. It comes in a sealed box, which Mum and Dad use to do the banking and which will cost lots of money to replace if something goes wrong!

The Raspberry Pi is cheap enough to buy with a few weeks’ pocket money, and you probably have all the equipment you need to make it work: a TV, an SD card that can come from an old camera, a mobile phone charger, a keyboard and a mouse. It’s not shared with the family; it belongs to the kid; and it’s small enough to put in a pocket and take to a friend’s house. If something goes wrong, it’s no big deal—you just swap out a new SD card and your Raspberry Pi is factory-new again. And all the tools, environments and learning materials that you need to get started on the long, smooth curve to learning how to program your Raspberry Pi are right there, waiting for you as soon as you turn it on.

A Bit of History

I started work on a tiny, affordable, bare-bones computer in 2006, when I was a Director of Studies in Computer Science at Cambridge University. I’d received a degree at the University Computer Lab as well as studying for a PhD while teaching there, and over that period, I’d noticed a distinct decline in the skillset of the young people who were applying to read Computer Science at the Lab. From a position in the mid-1990s, when 17-year-olds wanting to read Computer Science had come to the University with a grounding in several computer languages, knew a bit about hardware hacking, and often even worked in assembly language, we gradually found ourselves in a position where, by 2005, those kids were arriving having done some HTML—with a bit of PHP and Cascading Style Sheets if you were lucky. They were still fearsomely clever kids with lots of potential, but their experience with computers was entirely different from what we’d been seeing before.

The Computer Science course at Cambridge includes about 60 weeks of lecture and seminar time over three years. If you’re using the whole first year to bring students up to speed, it’s harder to get them to a position where they can start a PhD or go into industry over the next two years. The best undergraduates—the ones who performed the best at the end of their three-year course—were the ones who weren’t just programming when they’d been told to for their weekly assignment or for a class project. They were the ones who were programming in their spare time. So the initial idea behind the Raspberry Pi was a very parochial one with a very tight (and pretty unambitious) focus: I wanted to make a tool to get the small number of applicants to this small university course a kick start. My colleagues and I imagined we’d hand out these devices to schoolkids at open days, and if they came to Cambridge for an interview a few months later, we’d ask what they’d done with the free computer we’d given them. Those who had done something interesting...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.8.2014 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Informatik ► Weitere Themen ► Hardware |

| Schlagworte | beginner Linux • beginner programming • beginner Raspberry Pi • Computer Hardware • Computer Science • Eben Upton • Gareth Halfacree • Hardware • Informatik • learning Raspberry Pi • Mikrocomputer • Minecraft for Raspberry Pi • Raspberry Pi • Raspberry Pi add-ons • Raspberry Pi Arduino • Raspberry Pi Camera • Raspberry Pi configuration • Raspberry Pi Foundation • Raspberry Pi Gertboard • Raspberry Pi guidance • Raspberry Pi how to • Raspberry Pi instructions • raspberry pi manual • Raspberry Pi official guide • Raspberry Pi programming • Raspberry Pi software • Raspberry Pi tutorials • Raspberry Pi User Guide 3rd Edition |

| ISBN-10 | 1-118-92167-4 / 1118921674 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-118-92167-8 / 9781118921678 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,0 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich