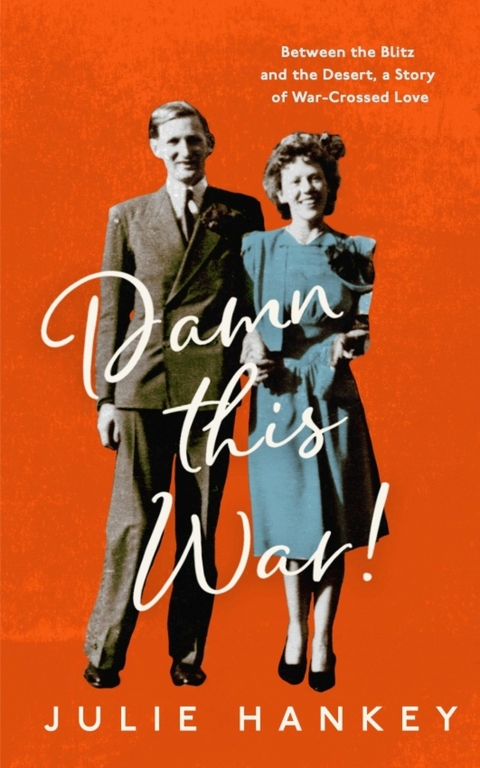

Damn This War! (eBook)

304 Seiten

Icon Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-83773-037-7 (ISBN)

With Damn This War!, Julie Hankey completes a trio of family histories based on a large cache of letters and photographs reaching back several generations. The first of these was A Passion for Egypt, a biography of her archaeologist grandfather who worked in Egypt before the 1914-18 war. Out of that grew Kisses & Ink, largely about the Victorian and Edwardian women in the family. Damn This War! tightens the focus onto the author's parents and brings the story up to the end of Second World War and its aftermath.

Julie Hankey is the author of A Passion for Egypt and Kisses and Ink, books that draw on private letters and wider research to bring the past to life.

Chapter 2

‘Damn this war’

In Birmingham, Tony was heartsick – though he was also in luck. The Friends’ Ambulance Unit was set up in the grounds of a mock-Tudor mansion belonging to a Birmingham Quaker family – the Cadburys, philanthropic cocoa and chocolate magnates. As it happened, a godfather of his knew the Cadburys and had written to say Tony was coming. So when the lady of the house, Dame Elizabeth Cadbury, invited the camp commandant to lunch, Tony was included in the party: ‘rather an honour’, he told Zippa, ‘as everyone here seems to worship her.’

She really is perfect, a pile of white hair, thin, erect, with an ebony stick … She has a hand in everything and rules them all. Lunch was good, a great patriarchal table, adoring middle-aged nieces, their husbands and children. She informed me there were 37 grandchildren and four great-grandchildren.

After that, he was invited to tea by one of the sons, the current managing director of the factory, and had a lovely time at that house too – ‘bristling with every possible luxury’, including a proper bath which they offered him, with bath salts. Tony made friends with his host’s children, two boys of twelve and thirteen, ‘so natural and friendly’, and ‘two sweet little girls, 7 and 3’. The five of them got on famously and Tony was asked to come again the following Sunday.

Now he was back in his hut, lying on his bunk bed, and had decided to cut both supper and prayers so as to use the quiet of his dormitory to write Zippa a long letter. A good fire was roaring in the stove (it was early January) and the few other men around him were also writing. He wanted her to know not only that he loved her, but how he loved her, and all the things she meant to him – her ‘gaiety and courage’, her ‘perfect taste’, and her ‘sense of rightness in things and the proportion of things’: ‘I do really get a feeling of strength and help from you … You are something of which I am absolutely and utterly certain, and I know so surely that you could never be different.’

But then comes this: ‘I don’t think I have ever before in my life had any person except Mummy I suppose, in some ways, from whom I got help. I have been very fond of people and felt that I cared for them and would do a great deal for them, but never that they could really help me.’ He sounds very young – as indeed he was, still only 21. But Zippa might have paused a moment over his remark about ‘Mummy’. Was Tony really looking for a mother, another, better mother? Tony’s ‘I suppose, in some ways’ is rather grudging. Much more fun to have Zippa, with all her gaiety and strength. In fact, Tony himself might have been a little uncomfortable – putting Zippa and his mother into the same sentence. For he quickly goes on to hope that she, in turn, will let him help her:

Darling do let me, because it is never really any good if it is one sided … I am so frightened sometimes of your self reliant side … you make me so happy and I rely on you so much and care so terribly terribly that it should be alright and that I should be able to do and be the things you want.

What exactly he thought she wanted him to do and be, let alone what he himself wanted to do and be, is left hanging. The truth was, he had no idea. The war had claimed him before he had experienced anything much beyond university. All through the war years he would wonder what he was good at. He had no particular wish (or so he said) for much more than a ‘sufficiency’ of money – just ‘an opportunity to have some little influence on things for good rather than ill’. At different times he thought he might be a journalist (like his father), or a teacher, a farmer maybe (like Veronica?), a businessman (not often), something in politics. Thinking perhaps of Zippa and Alured and the people they knew, he once warned her that he didn’t think he was an artist of any kind.

In one of Elizabeth Bowen’s novels, set in London during the war, there is a character, Roderick, a young soldier of about Tony’s age. He too has little idea of what else he might do: ‘since he was seventeen,’ she says, ‘war had laid a negative finger on alternatives; he had expected, neutrally, to become a soldier; he was a soldier now … Everybody was undergoing the same thing.’1 Something like that had been at work in Tony. He once told Zippa that he had known there would be war ‘ever since I was about 15’ – since 1933, that is, and Hitler’s rise to power. That conviction had been at the root of his pacifism. He had always been sure, he said, that the next war would have ‘no rules, no limits, that there would be mass bombing’. Events, of course, were to bear him out. When, much later on, in mid-August 1943, Zippa wrote of her dismay at the bombing of Italy,* he replied with a weary shrug: ‘What will you?’ he asked. What did she expect? ‘It was all implicit in ’39, and that was why I was a pacifist.’

That generation was acquainted with war. The First World War was there, just behind them, over their shoulders. If they didn’t remember it directly as small children, they knew it from their parents, their teachers, their older contemporaries. Alured was old enough to have memories of newly maimed men – soldiers he had seen at close quarters in a nursing home run by a great-aunt. Such men remained scarred. In 1928, a decade after the end of that war, when he was 21, he saw something that he put in a letter to his grandmother Mimi. He was on a walking tour in northern England, staying in hostels and sharing washrooms. In one of these, a man

showed me a gash down his whole back and thigh from a shell during the war, that had blown all the flesh away, and had battered his head against a tree so that his scalp was skinned and hung over one ear. You could see the great weals round his head – and his arm, which was such a funny shape and had a dent in the middle like a bite out of it, had been cut in two; and a skilful doctor had fixed it together, and had patched and sewn him up into shape out of a muddle covering several square yards of ground. It was amazing. His whole battalion had been wiped out, and he was the only survivor of the lot.

The odd thing about this description is not so much the horror (though there is that) as the cool curiosity of it – as though it were an interesting and rather extreme example of something he and Mimi both knew about. Whether Alured told his sisters, who would have been thirteen, fourteen and fifteen at the time, I don’t know. But a few years later, with Hitler’s rise and with the Balkans, Greece and Spain all engulfed in revolution and civil war, they began to get the horrors themselves. Veronica’s diary tells of the ‘dreadful dreams about war’ that she and Zippa were having as early as 1934. In 1935, she talks of gas masks and trenches and hideous death:

When I think to myself of any one member of my family dying, and I see all through the night, visions of them lying in many twisted and contorted positions, my mind is hollow and full of knocks and my heart swells so it goes right up into my head … It must be the same with everyone.

In 1938, with Hitler’s coup and the Anschluss and the Jewish persecutions, the thing crept closer still. It was on the doorstep. Veronica listened to the refugees she came to know and especially to her friend Israel, until she wanted, she said, to ‘weep with him for the Jews in Austria’.

What distinguished Tony from Elizabeth Bowen’s young Roderick, was that he wasn’t neutral about being a soldier. Soldiering, in his view, put a block on real life. It was an interruption, a hiatus. Life proper, whatever that was, could start only on the far side of it. ‘Damn this war Darling,’ he once wrote, ‘I do so want to get on and start living.’

That was in 1942, but the feeling was already there in his first months in Birmingham. Almost from the beginning, he felt restless and impatient. It was something they both felt, Zippa too – ‘restless as the Devil’, she told Alured, ‘I have the feeling of no time to be lost’. Tony told her about the things they had to do at the camp, about orderly duties, a route march, night ops and all the ‘boy scoutery’* of training generally. He wrote about a revue they were getting up and a dance he was going to: ‘all very well’ he said, ‘but damn silly and I don’t want to be in Birmingham. I want to be in London, do some work, marry you at once and not waste silly time.’

The worst of it – though it was odd to say so – was that nothing much seemed to be happening. People put up their blackout curtains, but no bombs dropped. The guardian dragons swung in the sky, but no planes flew over. Men joined up, but there were no active fronts. Evacuated children were even trickling back. For a moment Tony thought there was a chance for diplomacy. In March 1940, he wrote to his father in India:

I wish we would take some diplomatic initiative and be more precise about the kind of world we want to create. I wish we would mention a few sacrifices we would be prepared to make … we might remove the suspicion that still exists everywhere that all we want is a return to the British Imperialism of 1912.

He hated the smugness and hypocrisy, as he saw it, of the press and politicians. He winced at the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 9.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Schlagworte | A nurse's war • Blitz • daniel finkelstein • Eileen Alexander • harry leslie smith • heartache on the homefront • Hitler • Lara Fiegel • Letters from the Suitcase a wartime love story • Love Among the ruins • Love in the Blitz • mum and dad • Second World War • Stalin • The Lovecharm of bombs • wartime romance |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83773-037-7 / 1837730377 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83773-037-7 / 9781837730377 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 635 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich