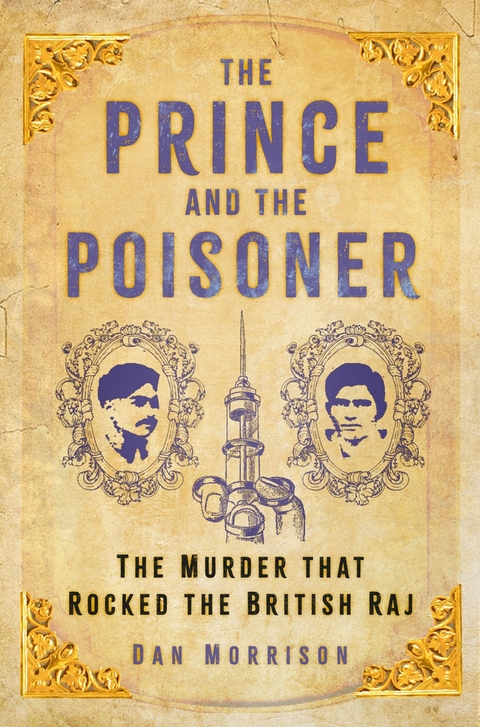

The Prince and the Poisoner (eBook)

240 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-605-9 (ISBN)

DAN MORRISON is a regular contributor to The New York Times, Guardian, BBC News and the San Francisco Chronicle. He is the author of The Black Nile (Viking US, 2010), an account of his voyage from Lake Victoria to Rosetta, through Uganda, Sudan and Egypt. Having lived in India for five years, he currently splits his time between his native Brooklyn, Ireland and Chennai.

2

These Jealous Impulses

As the family gathered in the shadow of their carriage, Amarendra described a collision with a short, muscular stranger, ‘not a gentleman’, wearing traditional homespun cotton, who’d barrelled into his right side, ricocheted away, and vanished among the thrust of travellers.

Amarendra’s beige shirtsleeve was wet with an oily substance the colour of clarified butter; he rolled it up and the party gathered to stare at a damp spot on his upper right shoulder marked by a solitary pinprick. His niece, Anima Devi, stood on her toes and scanned the crowd in a futile search for the assailant. Rani Surjabati felt a chill and leaned on the piled baggage for support. She had experienced the deaths of her husband, her brother-in-law, sisters-in-law, and an adopted daughter. She stared at her young ward, full of foreboding.

As the women boarded the train, Amarendra’s cousin, Kamala Prosad Pandey, insisted he remain in Calcutta and have his blood tested, and for a moment Amarendra appeared to waver. Then his dada, his elder brother, pushed through the crowd, seized the affected arm and, peering at the strange wound, rubbed the oily red dot with his bare thumb and laughed. Benoyendra accused them of ‘making a mountain out of a molehill’. He bore down on Amarendra ‘and, in a way,’ Kamala recalled, ‘forced him into the compartment.’

‘That is nothing,’ Benoyendra said, manoeuvring Amar to his seat. ‘Go home.’ The cousin protested, but Benoy cut him off: Amarendra had but one elder brother, and even as an adult he was duty-bound to obey. Everyone knew this, lived this. Kamala backed off. Even in extraordinary conditions, the old ways prevailed. With characteristic obedience, Amarendra stayed on the train, ceremonially touching his brother’s feet before Benoy departed.

It was his final capitulation. There the boy sat, miserable. Surjabati lay stretched out on the bench opposite. His sister Banabala produced a bottle of iodine and daubed at the wound. Amarendra asked for a knife to cut away the affected flesh, but no one was carrying a blade. They rattled on.

As the locomotive bore north to the comforts of home, Amarendra’s body was already in the opening engagements of a losing battle with a killer that had once consumed half of Europe and that had been scything its way across India for more than two decades. The virulent germs the strange assailant had driven into his arm began to multiply, releasing endotoxins that would in the coming days cause at first scores, and then hundreds of tiny blood clots to form silently throughout Amarendra’s body. Their blood supply being choked off by these clots, Amar’s organs faced a slow death. With his body’s coagulants depleted, and colonies of pathogens growing exponentially, blood from Amarendra’s damaged tissue would soon begin seeping into his lungs.

Back home in Pakur, an uncle chastised Amar for having ever left Calcutta, with its world-class doctors, and begged him to return before he became ill with whatever had been stabbed into him.

With a resignation that can be heard, mournful as a bell, from that century to this, Amarendra replied: ‘My brother is determined to take my life. What precaution can I take?’

***

The Pandeys were wealthy zamindars: local gentry who had ruled over a poor area of subsidence rice farmers, black stone mines, and timber-rich forests since the days of the sixteenth-century Mughal emperor Akbar the Great. Over the course of more than 400 years, the clan had wrung every anna it could from the largely illiterate population of a realm bigger than modern New York City. In 1929, the Raja of Pakur, Protapendra Chandra Pandey, died and left the estate to his two sons, the half-brothers Benoyendra, 27, and Amarendra, 16. From a promontory on the third-floor verandah of the tallest building for miles, Benoyendra and Amarendra could gaze in any direction, over paddy, woodland and hamlet, satisfied that, by law, custom, and divine right, nearly all they surveyed was theirs.

Behind the walls of their whitewashed ancestral palace – a castle-like bastion built to withstand an indigenous peasant uprising – Rani Surjabati Devi raised them as her own. Despite an outward appearance of solidarity, the brothers’ relationship was defined by rivalry and resentment, and by Benoyendra’s need to assert himself as their father’s one true heir. Benoy would battle first for maternal love, and later for money and power.

As the son of a zamindar, Benoyendra had enjoyed a luxurious childhood, raised in a palace, attended by servants, with nannies and tutors to keep him company and assure his proper upbringing. His education would include lessons in English, Bengali, horsemanship, and shooting. Benoy’s mother had died when he was just 3 years old, and Surjabati moved into the Gokulpur Palace to care for him and his younger sister Kananbala, serving as a rock of love and continuity. She stayed on after their father remarried and, when the raja’s second wife died after childbirth, she took on Benoyendra’s half-sister Banabala and the newborn Amarendra, who would never know his birth mother. As the boys grew to adulthood, Surjabati remained a pivotal figure in the household – they called her ‘Mom’ and ‘Mama’.

It would have been natural for Benoyendra to feel some small resentment of the new baby. In a culture where sons were prized well above daughters, Amarendra’s arrival represented a dilution of Benoy’s supremacy, despite his unassailable position as the eldest male. But when Amarendra’s mother died of complications from childbirth, Benoyendra suffered a more severe blow, as Surjabati swept in to care for the motherless newborn and his toddler sister. The tiny boy was hers from almost his first moment; in an instant, Surjabati’s love for Amarendra eclipsed her motherly bond with Benoy. He never forgot it.

Twice robbed of maternal affection, Benoyendra responded to this emotional dethronement with a lifelong resentment of his aunt and the pretender Amarendra. He would evolve into a grandiose figure, rebelling against the careful and rigorous social mores of his community, using money as a weapon against his closest family, and finally turning to violence to excise this narcissistic injury. Sigmund Freud was referring to relations between sisters when he wrote, ‘We rarely form a correct idea of the strength of these jealous impulses, of the tenacity with which they persist and of the magnitude of their influence on later development,’1 but he could just as well have been observing Benoyendra’s festering animus for his younger brother. Despite his father’s favour and his primacy as the future raja, Benoyendra saw himself as the odd boy out, and now saddled with a co-heir whose well-being he would one day be responsible for.

Compared with most Indians of that era, the Pandeys were unimaginably wealthy. Even by international standards they were rich, with an estate producing income worth a princely £20,000 a year at a time when English farm workers were taking home a little more than a pound a week,2 and most Indian incomes amounted to mere pocket lint in London and New York. The family’s privilege was tethered to the land, and to the time-bound mores of the rural nobility. Long before the forces of Robert Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daulah at Plassey, before Job Charnok set up the malarial Ganges River post that would become Calcutta (now Kolkata), the forested hills and fertile valleys surrounding Pakur, 174 miles upstream in a region known as the Santhal Parganas, had already been under the rule of ‘outsiders’ for centuries.

The Pakur Raj dynasty descended from north Indian imperialists, a clan of Kanyakubja Brahmins born on the plains near Lucknow who arrived in the late 1500s to tame the rough lands and peoples found near the eastern margins of the Mughal Empire. They would rule over the region’s tillers and indigenous hill people in the name of Akbar the Great.

Their leader was one Sulakshan Tewary, who had seen his ancestral properties in the north turn lifeless from an ‘all-pervading pestilence’.3 Rich, unclaimed lands, however, were available in the east for a freebooter brave or desperate enough to pull up stakes. Tewary secured a land grant, or jagir, from the emperor for a wild, unconquered place neither had ever seen. As a zamindar, with the powers of a small monarch, Tewari would fold this virgin territory into the Mughal embrace and convert its thousands of peasants into Akbar’s loyal, rent-paying subjects.

Tewary and his followers made a rutted journey halfway across the subcontinent to fulfil this manifest destiny. The train of newcomers made a slow advance through dense jungle dotted with villages and hamlets, until finally it reached a stretch where India’s vast, green flatlands gave way to hill country and the great Ganges delta, a place of swaying sal trees, Bengal tigers, and small farms raising rice and pulses. This was now home.

Akbar’s writ notwithstanding, the local farmers and strongmen, led by a skilled archer named Satyajit Roy, chose to resist the Persian and Awadhi-speaking invaders. The sons of the soil drew first blood but ‘were soon pacified and agreed to pay rents out of which the due amount of imperial tribute was remitted to Delhi’.4 A new dynasty was born. Tewary restored his finances off the backs of his new subjects, while they adjusted to the novelty of having an emperor to support. The new...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.3.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror ► Krimi / Thriller | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1933 • amarenda pandey • British India • British Raj • Calcutta • calcutta railway • Churchill • e henry le brocq • Gandhi • indian true crime • jazz age india • kolkata • Murder Medicine the Movies and a Crime that Rocked the British Raj • Nehru • the black nile • the devil on the white city • The Patient Assassin • thirties • true crime india |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-605-6 / 1803996056 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-605-9 / 9781803996059 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich