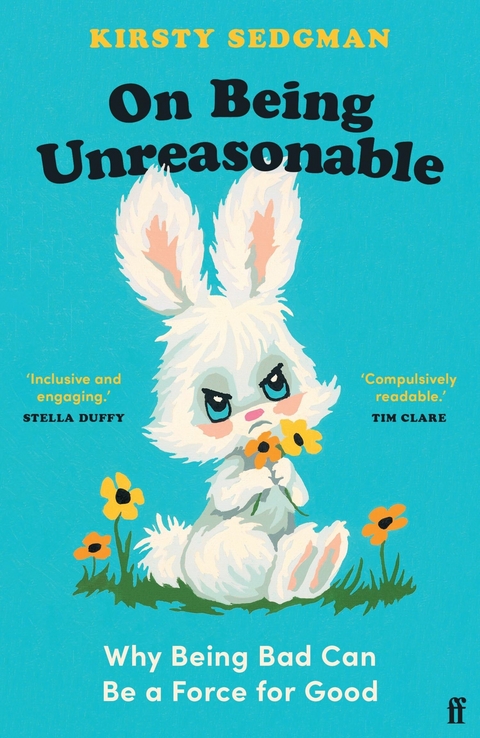

On Being Unreasonable (eBook)

288 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

9780571366873 (ISBN)

Kirsty Sedgman is a cultural studies expert who specialises in audience experience and human behaviour. She has spent her career studying how we construct and maintain our competing value systems, working out how people can live side by side in the same world yet come to understand it in such totally different ways. Currently based at the University of Bristol, she has spoken about her research around the world, and has seen her work featured in outlets like BBC Front Row, the Times Literary Supplement, the Guardian, and the New York Times.

Manners, order and respect... these are all ideals we subscribe to. In opposed positions, we ought to be able to 'agree to disagree'. Today's world is built from structures of standards and reason, but it is imperative to ask who constructed these norms, and why. We are more divided than ever before-along lines of race, gender, class, disability-and it's time to question who benefits the most. What if our propensity to measure human behaviour against rules and reason is actually more problematic than it might seem?Kirsty Sedgman shows how power dynamics and the social biases involved have resulted in a wide acceptance of what people should and shouldn't do, but they create discriminatory realities and amount to a societal facade that is dangerous for genuine social progress. From taking the knee to breastfeeding in public, from neighbourhood vigilantism to the Colston Four-and exploring ideas around ethics, justice, society, and equality along the way-Sedgman explores notions of civility throughout history up to now. On Being Unreasonable mounts a vital and spirited defence of why and how being unreasonable can help improve the world. It examines and parses the pros and cons of our rules around reason, but leaves us with the rousing question: What if behaving unreasonably at times might be the best way to bring about meaningful change that is long overdue?

In December 2014 I was sitting on a bench in the jewellery room of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, sweating profusely. My entire upper half, from the top of my head down to my waist, was entirely covered by my thick woollen coat, like a kind of rubbish invisibility cloak. Inside I was struggling to cram my nipple into the mouth of my three-month-old baby, Monty, and achieve what the midwives called ‘a good latch’.

I’d chosen that space in the museum because a) it was dark, b) there was something padded to sit on, and c) I was desperate. Monty’s cries had revved up fast – from gentle grumbling to lawnmower to XF-84H Thunderscreech* – and people were starting to tut. Around us, a swarm of posh older visitors were busy feigning interest in the jewels sparkling in their cases while muttering to each other about the woman hiding under a coat in the middle of the room, and what is she doing and should we call security?

I don’t know how many of you have ever breastfed a baby, but it is brutal. Pre-children, this is how I thought it worked:

- Cradle baby in arm

- With other arm, veil maternal bosom in modest cotton cloth

- Pop nipple out and point towards baby

- Breastfeeding achieved!

In reality, in my experience it usually went more like this:

- Clutching baby, peel nursing bra slowly down—

- Oh god, turns out bra was the only thing holding milk in! Milk now shooting everywhere!

- Clutching nipple in one hand and baby’s neck in the other, carefullllllly bring them together …

- Quickasaflash, ram nipple into baby’s mouth at precise forty-five-degree upward angle so enough breast tissue gets over his hard palate before he clamps dow—

- OW! NOT FAST ENOUGH! HE’S CHOMPED THE TIP! OW OW OW!

- Gritting teeth, retreat (to sound of vacuum sucking and skin ripping) then try again …

- After a few goes, finally get position exactly right – then sit through toe-curling pain, absolutely rigid and still for fifteen to thirty minutes so latch doesn’t slip and leave nipple white, cracked, and bleeding

- Repeat steps 1–7 with Boob Number 2.

I didn’t realise it at the time but at that precise moment, just a few miles down the road, forty other women were standing outside Claridge’s hotel feeding their own infants. No woollen modesty-blankets for them – just a bunch of signs saying things like ‘That’s what breasts are for, stupid’ and ‘In future I’ll be taking my breast at the Ritz!’

This ‘Storm in a D-Cup’ was part of a nurse-in protest organised by breastfeeding campaigners. It had been prompted by an incident a few days earlier, in which a woman tweeted a photo of herself covered in a starched white tablecloth after Claridge’s staff asked her to cover up her feeding baby. Her tweet about feeling ‘humiliated’ by Claridge’s request made front-page news after Nigel Farage – that bastion of balanced opinion – said in a radio interview that surely ‘it isn’t difficult to breastfeed a baby in a way that’s not openly ostentatious’.

Thankfully I didn’t read about all this until after I’d got home from London, our first real outing from rural mid-Wales since Monty’s birth. Until then I’d only ever breastfed at home,† and the whole experience nearly terrified me into never going out in public again. Watching the debates unfurl online, I saw hundreds of my fellow Britons frothing at the mouth over the possibility that they too might one day have to share a restaurant with ‘space-hopper udders’ and expressing disgust at all those women unceremoniously plonking their breasts on the table left, right, and centre. Um, I know they’re often called ‘jugs’, but I think you’re getting a little confused …

Peel aside the inflammatory vitriol, though, and underneath there’s rather a seductive idea. All we want is for people to be reasonable. In the online comments I noticed this exact word showing up again and again. Claridge’s baby-concealment actions were very reasonable, actually, when you consider that many people may potentially be embarrassed by the sight of a feeding child. It was unreasonable for the mother to take it for granted that everyone would find it acceptable. As most reasonable-thinking people know, breastfeeding can be done discreetly. Farage’s statement, too, was totally reasonable – he was only calling for compromise and accommodation on both sides.

For any breastfeeding parents facing a similar dilemma, then, the answer is surely simple. It’s just about showing consideration for other people, who might feel uncomfortable at seeing a smidgen of side-boob, a whisper of décolletage.‡ It’s an obvious case of common decency, manners, and respect. Just act reasonably, folks! Why is that so hard?

That, as it turns out, is a very good question.

*

According to the dictionary, being a reasonable person means ‘having the faculty of reason’, which in turn means ‘possessing sound judgment’.1 This is a meaning that solidified in English around the 1300s, with the word resonable derived from the Old French raisonable, which in turn comes from the Latin rationabilis: from ratus, the past participle of reri, which means ‘to reckon, think’. When applied to objects rather than people, ‘reasonable’ today can also refer to things that are moderate, fair, or inexpensive: i.e. not extreme or excessive. This information comes from my favourite etymology website, which also tells me that the sense began to shift in Middle English. Initially meaning ‘resulting from good judgment’, and then ‘not exceeding the bounds of common sense’, around the 1500s ‘reasonableness’ came to mean ‘fairly tolerably’: to act, in other words, in a way that a fair-minded person would be able to tolerate.2

Moral philosophers have been commanding us in one form or another to just act reasonably for the past few millennia. Whether it’s Confucius in ancient China, or Aristotle in ancient Greece, or the Age of Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Europe, oceans of ink have been spilled debating which beliefs and behaviours are within reason and which are beyond the bounds of tolerance. This long history can help us understand what’s happening again today.

From Bolsonaro in Brazil to Putin in Russia, Trump in the USA to Alexander de Pfeffel (Boris) Johnson in the UK: right-wing politicians around the world have spent the past few years working harder than ever to encourage visible divisions over hot-button topics. Climate change and immigration, gun laws and gay rights, pro-choice vs pro-life: any public arena for debate has become a kind of Rorschach test for moral judgment. These divisions are playing out especially fiercely within the online realm. Just a quick scroll down my Twitter feed and – yep – there’s a cavalcade of police officers charging on horseback towards protesters. But are they deliberately inciting violence at a peaceful protest, or heroically defending democracy from a vicious mob? There’s a family of asylum seekers capsized in the ocean, feared drowned alongside their one-year-old child – but what some leap to decry as a human-rights travesty resulting from the wanton destruction of their country by our own, others call the inevitable consequence of an illegal invasion. There’s a respected professor campaigning for schoolbooks to teach children the full horrors of slavery – but are they cynically twisting the past to incite divisions, or simply trying to paint the unvarnished picture of a history which until now has been suppressed?

In the wake of rising populism and virulent misinformation, facing a world that seems to be slipping further and further out of our grasp, we’re desperately scrambling to re-establish the boundaries of civic morality on either side of the political divide. No wonder calls to ‘just be reasonable’ are growing louder and louder. But rather than learning to stand on the same moral ground, what we’re seeing is a widening sense of antagonism. All this talk is driving us further apart than we’ve ever been before.

I study audiences for a living, which means that I spend my days immersed in talk. More precisely: how do people talk about the things they see, read, and hear? Whether it’s a play by Bertolt Brecht or a political phenomenon such as the Brexit referendum, I’m endlessly fascinated by how people can watch the same event unfolding but come to understand it in such totally contradictory ways. You’ll see throughout this book that I’m spending a lot of time dwelling on the kinds of words people use when they talk about others: whether that’s via comments about a newspaper article, or arguments on Twitter, or the things people...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.2.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Schlagworte | coward • Dr Elizabeth Cripps • Fun Palaces • Shon Faye • stella duffy • The Transgender Issue • Tim Clare |

| ISBN-13 | 9780571366873 / 9780571366873 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich