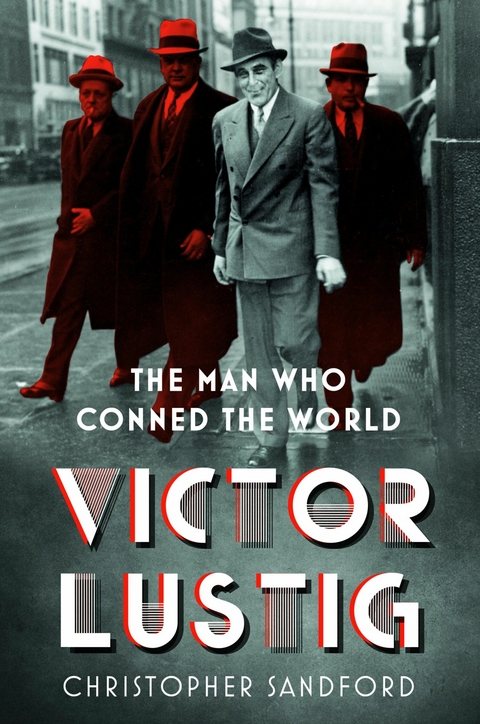

Victor Lustig (eBook)

320 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-9823-9 (ISBN)

That blemish aside, he was a man of athletic good looks, with a taste for larceny and foreign intrigue. He spoke six languages and went under nearly as many aliases in the course of a continent-hopping life that also saw him act as a double (or possibly triple) agent. Along the way, he found time to dupe an impressive variety of banks and hotels on both sides of the Atlantic; to escape from no fewer than three supposedly impregnable prisons; and to swindle Al Capone out of thousands of dollars, while living to tell the tale. Undoubtedly the greatest of his hoaxes was the sale, to a wealthy but gullible Parisian scrap-metal dealer, of the Eiffel Tower in 1925.

In a narrative that thrills like a crime caper, best-selling biographer Christopher Sandford draws on newly released documents to tell the whole story of the greatest conman of the twentieth century.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.7.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Al Capone • Alcatraz • austro-hungar • con artist • con-man • conman • Crime • Eiffel Tower • France • french archives nationales • Germany • Hoax • rumanian box • scam • The Man Who conned the World • Thriller • True Crime • Victor Lustig • Victor Lustig, The Man Who conned the World, thriller, al capone, eiffel tower, rumanian box, con-man, conman, con artist, austro-hungar, alcatraz, france, germany, french archives nationales, crime, true crime, world war • Victor Lustig, The Man Who Sold the World, thriller, al capone, eiffel tower, rumanian box, con-man, conman, con artist, austro-hungar, alcatraz, france, germany, french archives nationales, crime, true crime, world war • World War |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-9823-7 / 0750998237 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-9823-9 / 9780750998239 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich