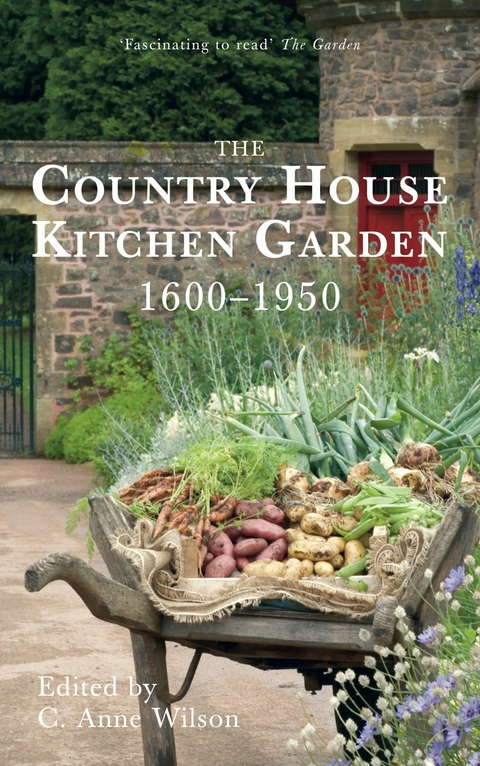

The Country House Kitchen Garden 1600-1950 (eBook)

192 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-5904-9 (ISBN)

INTRODUCTION

C. ANNE WILSON

This book is about the vital contribution from the garden to the provisioning of the country house during earlier centuries. The service buildings of the country houses of Britain have attracted a good deal of attention in recent years. In some of the former laundries, dairies, bakehouses and brewhouses enough of the original layout and equipment has survived to enable them to be restored with a fair degree of accuracy. However, the same cannot be said of that other great service area, the kitchen garden. The walls may still stand, and some of the greenhouses and frames may still exist, if only in a dilapidated state. But the arrangement of beds and borders disappeared completely once it ceased to be an economic proposition to manage the gardens according to earlier practices.

In former times such gardens supplied a large household with fruit and vegetables throughout the year. Now that household has shrunk. Country house families are smaller, and the previous array of domestic servants has dwindled to just a few helpers. Furthermore, the expense of the upkeep of the house itself has become such a burden that few owners would wish to maintain in addition the numerous heated glasshouses of the Victorian era, or to meet the wages bill for staff to grow exotic fruit and vegetables there year round. Nor is there any reason to do so, when the same exotics are widely available from greengrocers and supermarkets at a fraction of the cost of raising them in the British climate.

Though the former patterns of cultivation have disappeared, we can still gain a very good idea of how the beds and borders looked and how they functioned from the gardening manuals published from the later sixteenth century onwards in response to a keen demand from country house owners. Through these books we can trace gradually changing fashions in kitchen gardening. Visual evidence exists too, from several periods, in the form of engravings of individual gardens made as a record for the families who owned them.

Garden planning has been a popular activity in Britain for a long time. At first the gardeners tended to follow the practices of the Dutch and the French. But the many innovations introduced through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries meant that Britain’s kitchen gardens attained standards of excellence unsurpassed anywhere in continental Europe.

The kitchen garden at all periods was surrounded by walls, fences or hedges. These were useful in keeping out thieves – both animal and human. But an additional advantage was that they created a sheltered area with its own microclimate where vegetables and fruit trees could flourish.

The main walled kitchen garden eventually became very large, containing anything from 1 to 4 acres of ground. But even in the seventeenth century, when the kitchen garden was first separated from the ‘best’ or ornamental garden, many people also had smaller subsidiary gardens constructed for particular crops of a more permanent kind.

Artichoke gardens were much in favour in the seventeenth century. ‘Plant Artichocks in the new of the moone about our Ladie day in Lent [March 25]’, ran the instructions copied into Lady Elinor Fettiplace’s notebook in 1604, ‘& cut them close to the ground, & at winter open the earth about the root, & lay some dung therein, & in frostie weather cover the root over with dung.’1 Artichoke gardens were useful not only as a source of artichokes, much esteemed in the country house cuisine of the period, but also because they provided further wall space against which fruit trees could be raised. Separate walled nut gardens were sometimes created too, to provide protection for such trees as walnuts, almonds and sweet chestnuts.

In the main kitchen garden traditional vegetables were grown; but landowners were also eager to raise recently introduced varieties, such as cauliflowers, first grown in England shortly before 1600, and broccoli, which arrived in the later seventeenth century. In the orchard were planted some of the numerous apple, pear and plum varieties, often fairly local in origin, which came into fashion and went out again over the years.

Exotic fruits were raised in the country house garden throughout the period 1600–1950. In the seventeenth century oranges were grown in tubs, and were initially overwintered in sheds; but soon they were being accommodated in specially constructed greenhouses (so called because they held evergreens; myrtles as well as oranges and lemons were overwintered there) and orangeries. In the eighteenth century pineapples became the fashionable exotic fruit. Grown on hotbeds and under glass, the fully ripened pineapples crowned the display of fruits for dessert set out upon epergnes on the country house dining table.

Bananas were tried too, but proved less suitable for hothouse cultivation. The Revd J. Ismay visited greenhouses or ‘stoves’ (so called because heated by stoves) at Gawthorpe Hall at Harewood in Yorkshire on 13 May 1767, and reported that ‘The Banana was order’d by Mr Lascelles to be thrown out as too cumbersome and luxuriant for ye place’. But the head gardener showed the visitor ‘fruit-bearing Passiflora [passionflower]; it produced Fruit ye last year in high Perfection, the Pulp is eaten with Sugar and Venegar, it is more delicious than a Mellon, and has a much finer Relish’. He also saw sugar cane, figs and eggplants [aubergines]; and ‘ripe Alpine strawberries, Kidney Beans (ripe all winter), Grapes nearly ripe, Cucumbers, Oranges, Figs and Peaches as large as Crabs [i.e. crabapples: these were the young unripe peaches]’.2 Here we have a glimpse of some of the wide range of fruits and vegetables raised under glass to supply country house families in the later eighteenth century. Within a few years the Lascelles family were to leave Gawthorpe for their splendid new home, Harewood House, where in due course a large walled kitchen garden was constructed for them in a sheltered position close to the lake and more than a quarter of a mile from the house.

By that time the kitchen gardens of many country houses were being relocated far from their earlier position behind the house or next door to the flower garden. Sites were chosen, where possible, with a warm south-sloping aspect to encourage early ripening of the produce. Ideally the longer walls ran east to west, giving plenty of south-facing wall space for fruit trees. But the other walls could be used to advantage for later-ripening varieties, thus extending the season through which fresh cherries, apples, plums and pears could be eaten. Even the more tender fruits such as apricots and peaches could be enjoyed over a longer period by choosing south-facing walls for early varieties and west-facing walls for later ones. But eventually the season for enjoying fresh fruit and delicate vegetables was extended almost indefinitely by the development of the elaborate system of heated greenhouses maintained in the kitchen gardens of Victorian times.

Changes in gardening practice over three centuries were accompanied by changes in taste among those who ate the produce, leading to new fashions in cuisine. In the seventeenth century nearly all cooked dishes of fruit or vegetables were still heavily spiced, a legacy from the cookery of the upper ranks of society during the later Middle Ages. Surplus produce was preserved at home for the lean winter months, by drying, pickling and, in the case of fruit, increasingly by the use of sugar to create preserves and syrups. Many aromatic plants and flowers were cultivated in quantity to be the ingredients of home-made distilled waters, potions and salves. The lady of the house learned the medical lore which enabled her to prepare and use them to treat the ailments of family members, household servants and neighbours. But by the nineteenth century herbal medicine was on the wane; and the labour-intensive home distilling of herbs, flowers, seeds and roots to extract their virtue was dying out. Fruit and vegetable cookery was taking on a more modern look, while fresh hothouse fruits and tender vegetables were becoming available to the country house family through most of the year.

How far was the kitchen garden an economic success? Its produce fed the family, the indoor servants, and to some extent the outdoor workers (though they were also supported by their own gardens attached to their estate cottages). Although garden work is labour-intensive, wages were low, and when extra hands were needed at certain times of year for jobs such as weeding and the picking of bush fruit, women were employed – often the wives of estate workers – at a still lower wage. Other products of the estate could be used to increase the fertility of the garden: dung from the stables, fresh loam from the fields, leaf mould from the woods and from there also firewood to heat the greenhouses (eventually replaced by coal in Victorian times). Surplus produce was sold, the profit either going back to the family or to the head gardener according to the arrangements made by individual landowners.

On the debit side was the cost of seeds, when they were purchased rather than collected from the previous crop, and of new plants and fruit trees, including exotics. At the beginning of our period the expenses of the kitchen garden were probably counterbalanced by the overall benefits received from it. Towards the end, while parts of the garden remained cost-effective, the maintenance of several heated greenhouses, with three or four ‘indoor’ garden staff working full-time to tend the exotic fruit and other plants inside, must have been quite an expensive luxury. The country house family was repaid by being able to enjoy, and offer to guests, southern...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.3.2010 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Garten |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | 1600 • 1950 • Country House • country house, kitchens, kitchen, country houses, grow your own, produce, fresh produce, households, fruit, vegetables, digging, sowing, garden, walled garden, sustainable, lifestyle, natural medicines, medicine, medicines, remedies, gardening, seed catalogues, 1600, 1950 • Country Houses • digging • Fresh produce • Fruit • Garden • Gardening • grow your own • Households • Kitchen • kitchens • lifestyle • Medicine • Medicines • natural medicines • Produce • remedies • seed catalogues • Sowing • Sustainable • vegetables • WALLED GARDEN |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-5904-5 / 0750959045 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-5904-9 / 9780750959049 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 361 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich