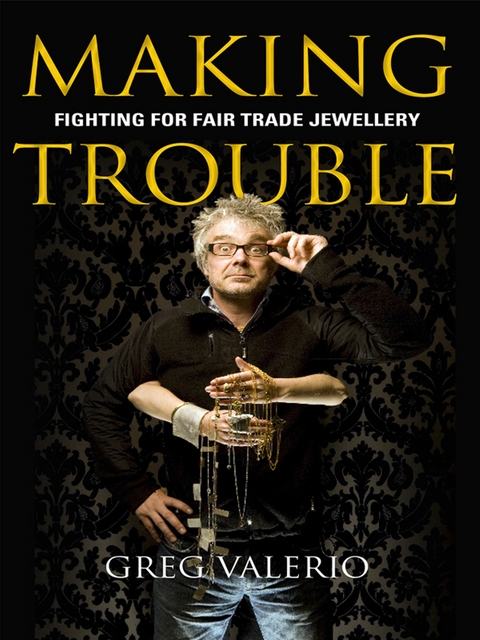

Making Trouble (eBook)

208 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-7459-5754-8 (ISBN)

Valerio, you're a natural born trouble-maker. Just make sure you make trouble for the right reasons. Expelled from secondary school with these words ringing in his ears, it took Greg Valerio a little while to find the right cause to devote his trouble-making skills to but eventually he found it. Fighting to apply fair trade standards to the jewellery business has brought him up against an industry riddled with problems. In the last fifteen years he has criss-crossed the globe, from the arctic circle of Greenland, alluvial diamond fields of Sierra Leone and equatorial gold rich rainforests of South America, in an effort to give the customer an ethically pure piece of jewellery, and to give the producers of that jewellery a fair wage and good working conditions. Along the way, he has exposed the jewellery industry's dirty secrets: pollution, child labour, criminality, exploitation, dangerous working practices and much more. And he has passionately argued his case in boardrooms, sumptuous hotels and with government officials from Antwerp to Cape Town, to say there is another way. Having been told it was impossible to have gold jewellery that could be certified as fairly traded from the mine to the shop, he achieved this in the UK. Founder of Cred Jewellery in 1996, he was awarded The Observer Ethical Award 2011 for Campaigner of the Year.

CHAPTER TWO

We met in November

And you kissed me so sweetly.

You cried as you told me

There was no bread to eat

So I brought you an ice cream

And watched your teeth scream

“Justice not Charity” became my slogan. Over the winter of 1993, I refocused the work under the name Christian Relief Education and Development, or CRED for short. My goal sharpened to engaging young people through both development education and campaigning, and also through holistic lifestyle changes. This seemed to me to be the only way I could move the work away from the delivery of intellectual knowledge, and root it in daily choices. For me, good campaigning meant three simple things: good education that leads to positive action, and then a change in lifestyle that cements campaigning into daily living.

This is where the fledgling Fairtrade movement proved so powerful; communicating fair trade principles to my audience became routine. All the young people I addressed were encouraged to lobby their schools to use Fairtrade products wherever possible. There is no doubt I upset a lot of dinner ladies and school accountants whose primary focus was cheap food, not Fairtrade.

The more I reflected on my trip to Tanzania, the more challenged I became about the structure one needed to deliver change. Our schools programme was legally defined under the charitable status of the local church. And its growing popularity meant we needed to expand it beyond our existing funding partner, Christian Aid. So I began to apply for financial support from Oxfam, Save the Children, and the European Union.

I found this often led to real challenges for some of the funding agencies, clearly confused by the idea of a local church delivering a socially empowering international justice message. They continually assumed we had an ulterior motive and really just wanted to convert people. The political correctness of some of the mainstream secular British development agencies at the time, I felt, was being used as a mask to avoid their own institutional discrimination. In most cases CRED would apply for a development education grant, could demonstrate a very high quality of delivery, yet fail to get funding on the grounds “We do not fund religious organizations”. It was very frustrating.

My local church had been fantastic in getting me launched, and they had incubated the entire development education programme, but the new distinctive message of justice for the poor began to create a certain amount of tension in the Pioneer network of churches that my local church belonged to. For some of its leadership, achieving a national evangelical revival was the most important thing, and justice for the poor was a secondary outcome to a national spiritual revival. I did not agree.

This came to a head when I was asked to write an article in the network’s magazine on “Where Justice Meets Revival”.

In my article, I explained that the question was framed incorrectly. It was more about how a view of revival fitted in with God’s commitment to the poor and the oppressed. I explained I was not an evangelical so a revival agenda was not my priority, and that the lifestyle of the church needed to reflect this commitment through campaigning, buying Fairtrade products, boycotting Nestlé, and giving away the church’s wealth in service of the poor. The then leader of that network denounced my approach by writing a critical letter (under a pseudonym) expressing his concerns that I would slip off into heresy if I abandoned evangelicalism. Pursuing justice was viewed as a sexy message by sections of the broader church, but not a core activity. I felt like I was caught between a rock and a hard place. I was too Christian for the secular boys, and too secular for elements of the Christian fraternal.

In November 1994 I travelled to Ethiopia, as I had been asked by a leader of a church in Derby to contribute to a youth conference. He wanted me to talk about my work with CRED and our human rights education. It proved to be an important watershed for me, and also marked the beginnings of my relationship with the jewellery trade. The country had impacted me hugely during the mid 1980s, and the opportunity to visit was too good to turn down. Going to Ethiopia gave me the chance to make good on my promise to visit Africa every year, and also meant I would witness urban poverty in one of the poorest cities in the world, Addis Ababa.

Arriving in Addis was an explosion of emotion, an assault on the senses, and a harrowing of my consciousness. As we travelled around the city over the ten days of our trip, I struggled to take in the sheer complexity of life. Huge swathes of the city lived in abject destitution with little or no hope. I was numbed by the mass of human suffering on a scale I could not absorb. Every road junction we stopped at, we would be engulfed by a rugby scrum of children begging for food, three or four deep at our window. Women would offer us their children to take home, and the disabled pleaded for help with eyes full of sheer desperation. How could this be? In Tanzania the rural poverty had been acute and disturbing, yet here in Addis, the sheer number of people in the city meant the immediate impact of their poverty was magnified a hundredfold.

There simply was not enough emotional depth in my life to deal with this level of human suffering. I was reminded of Stalin’s famous quote, “One death is a tragedy; one million is a statistic.” It is always easier to cope with the moral outrage and any sense of guilt if you can rationalize the enormity of the problem into a statistical set of numbers. I was well versed in the statistics via the United Nations Annual Development report, but numbers and statistics become irrelevant when faced with the spectre of death in the eyes of a malnourished child. Where was the hope? The Jesuit priest Jon Sobrino once said, “The highest authority on the planet is the authority of those who suffer, from which there is no appeal.” I now understood what he was talking about.

Having been invited to contribute to a Christian youth conference on the Justice of God, I was struggling to deliver my material in the face of such daily suffering. I felt like a fraud. But my salvation came in the shape of Meron and Sarai, two street girls who were asking for me by name. “How can this be? I do not know any street girls,” I wondered.

Naamen, our host and translator for the trip, knew both the girls and had told them that the team that I was a part of were in town. This at least explained how they were able to locate us, but I never did find out how they knew to ask for me by name. The girls began to tell me their story. Meron had been orphaned as a toddler. Both her parents had walked to Addis in 1985 during the famine and had died on the journey. Sarai’s mother had abandoned her and her father was dead. Both the girls had been living on the streets behind the Ethiopia Hotel since they could remember, and were prostitutes. I made an educated guess that both girls were around eleven or twelve. Older boys regularly raped them. Their lives were violent, abusive, and loveless. Here were two little lives that had been tragically impacted by the famine of the mid eighties, the living legacy of a lost generation.

We took them for an ice cream, as they said they had never tasted one. The coldness of ice cream on their teeth was painful for them, and we all wept with laughter at the way they spooned it into their mouth, spat it out, and waited for it to melt so they could drink the slush from their bowls.

Having listened to them, I became very concerned for their welfare and wanted to take them to a doctor so they could get a health check and HIV test. Nick Pettingale, the leader of our team, told me to visit a woman called Sister Jember Teferra who ran a project in the four poorest slums in Addis called the Integrated Holistic Approach Urban Development Project (IHA-UDP). I would later discover why it was called this – “So the government or individuals cannot corrupt our approach to poverty alleviation,” Jember informed me.

What she meant by this is that one of the biggest battles in any new organization is how to stop individuals – or in some cases, governments – from trying to take over a successful process and make it serve their own need for fame and fortune or a political agenda. Enshrining the approach to poverty alleviation in the name of the organization was one of Jember’s ways of preserving the integrity of what they were doing on the ground with the poor.

Sister Jember’s background explained even more. Everyone, including me, assumed she was a nun, because of her reputation as a campaigner and champion of the poor. In fact, her title of “Sister” referred to the nursing qualifications she had achieved on the wards of the National Health Service in the UK. Sister Jember was the niece of the emperor Haile Selassie, and had been educated in the UK in the 1950s and early sixties. After the military coup in 1974, the Dergue Regime had imprisoned her and her husband, and she had spent six years as a political prisoner. It was while in prison, as she tended to the needs of the dying and tortured prisoners, that she learned her approach to poverty alleviation.

I was profoundly moved by her story. Not only had she given up the privileges of her background, she had learned to forgive the regime that had imprisoned her and had emerged as a woman who would dedicate her life to the service...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.9.2013 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | Colour and b&w photographs |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Beruf / Finanzen / Recht / Wirtschaft ► Wirtschaft | |

| Technik ► Bergbau | |

| Wirtschaft ► Volkswirtschaftslehre ► Makroökonomie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7459-5754-4 / 0745957544 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7459-5754-8 / 9780745957548 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich