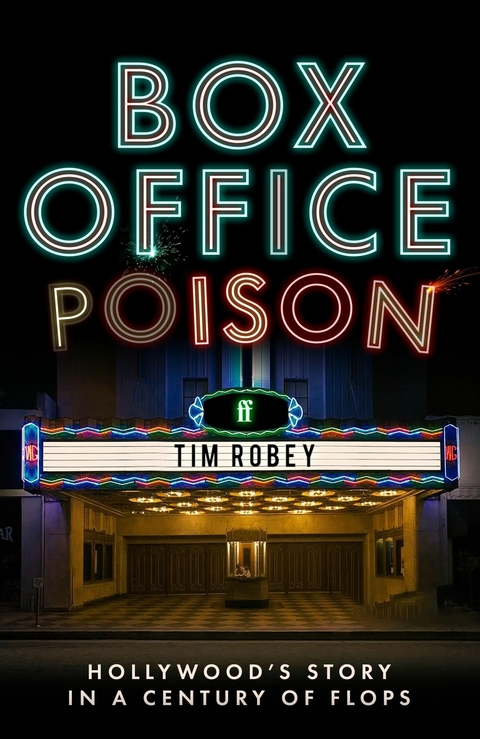

Box Office Poison (eBook)

244 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-38122-7 (ISBN)

Since 2000, Tim Robey has reviewed films, written features and conducted interviews for the Daily Telegraph's arts pages. He appears regularly on Radio 4's Front Row and Monocle FM Radio, contributed to R4's now-defunct Film Programme, and appeared as a sofa guest on BBC Film 2015-2017. He gave Cats zero stars, but has now seen it four times. His favourite film is Terrence Malick's The Thin Red Line (1998).

Histories of studio film-making have a habit of skimming over the disasters – those moments of doomed expenditure that pull the curtain back on what the culture was thinking. As in: what the hell were they thinking?

Failure fascinates, though, for all the reasons that sure-fire success is a drag. Merely log the highest-grossing films of a given decade, the Best Picture winners, and so forth, and you’re telling only a flattering fraction of the Hollywood story. You could also argue that the only genuinely interesting financial successes, in the world of cinema, are the ones no one saw coming.

James Cameron’s Titanic (1997) was widely tipped to be a fiasco, and left every box office record in its wake. The Blair Witch Project (1999) was made for peanuts by a bunch of film students no one had ever heard of. Those are extreme cases – arguably the two most extreme – of beating the odds. The vast majority of hits, in an industry notoriously averse to betting on anything other than proven certainties, fall into neither category.

Films that flop exorbitantly are the flipside to that norm, and thereby reveal a lot. Before their downfall, they were often dreamed up erroneously as sure things, by some backstage calculus derived from everything box office is meant to teach us – in terms of popular taste, demographic reach, star power, genre favouritism.

Harshly exposing the flaws in that business model, the saga of an archetypal flop has everything. Escalating budgets. Clashing egos. Acts of God. It’s far more compelling to read the story of an out-of-control Gigli (2003) than a machine-tooled megahit like Avengers: Infinity War (2018). This isn’t just because the prospect of a blockbuster crashing and burning attracts our instincts for rubbernecking, but because flops themselves can be such durably interesting artefacts.

They’re the medium’s weirdos, outcasts, misfits, freaks. They can be reappropriated after the event as camp treats; they can linger, Ozymandias-like, as monuments to studio hubris, hobbled and crumbling; or they can electrify decades later for reasons of genuine artistry, as misunderstood, radical, ahead of their time.

All of these categories will be explored here, case by case. In nearly a quarter-century (yikes) of reviewing professionally, I’ve had to deal in print with all manner of eye-watering abominations – some of these among the more recent debacles that have made the cut. But there’s a century of cinema to turn over, and I’m fascinated by what the bygone era can tell us with its turkeys.

The silent age, when film-makers were testing the boundaries of what this fledgling medium could achieve, saw the first monumental battles between art and commerce waged on screen, with directors, studios and stars hacking at each other in the fray. I’ve chosen two examples here that lost a fortune, and are among the most fascinating films of their day, not just for everything that went wrong, but for the creative ambition that survives in both pictures as we now have them.

Several other films in this book are near masterpieces. Their stark financial failure will be tackled, but so will their risky flexes and unorthodox brilliance. Each was deeply costly to the careers of those film-makers, who were sent to directors’ jail for having soaraway visions no one managed to sell. The least they deserve is retrospective appreciation for what they got on screen, however painfully unrewarded it went at the time.

Another subset of what’s included are what we might opt to call ‘disasterpieces’ – films with wild, commercially fatal problems but a peculiar integrity. There are some uniquely messy enterprises we can Preface behold with the benefit of hindsight and not really imagine, or even want, fixed. There’s an aura to such behemoths I’ve always found alluring: they might have defeated their makers, but somehow they live on, not least as test cases for how not to spend a studio’s millions.

The chosen films are a jumbled, motley crew – but that’s kind of the idea. Without knowing it, they all say something about the circumstances that saw them produced. And while plenty of them should be fed to the wolves head first, others can be held up as magnificent. Quality’s meant to be all over the map.

Instead, two main criteria govern what’s in. The production on each film has to have been epic or crackers, a comedy of errors, or in some way freshly entertaining to recount. (A few old warhorses are discussed only in passing, simply because they’ve been flogged to death.) On top of that, their commercial fortunes need to have been genuinely atrocious. Nothing here broke even, or nearly did. Nothing that was savagely panned by critics but crawled home with a modest profit (John Boorman’s berserk Exorcist II (1977), for instance) counts as enough of a bomb.

Waterworld (1995) needs a mention. It’s an instructive case of an at-the-time infamous bellyflop that actually wasn’t one, despite being a summer blockbuster released amid damning media coverage of hubris and overspend. It’s also not terrible, and that’s what saved it, differentiating it from Kevin Costner’s subsequent post-apocalyptic clunker, The Postman (1997). Waterworld cost Universal around $175m, an unprecedented sum at the time, but recouped $264.2m at the global box office. With the added expense of prints and marketing, this still left it marginally in the red; a few years later, thanks to ancillary revenues from home entertainment, it would have crossed the line.

*

It’s hard to say exactly when mainstream reporting began weighing in so avidly, and more often correctly, to predict flops. Industry bibles such as Variety have been totting up grosses and sussing out budgets since day one. Somewhere along the line, this tipped over into weekly sport across America’s breakfast tables.

News pages started trumpeting the victory laps of Star Wars (1977) at the same time as flaunting, with often gleeful Schadenfreude, the ballooning costs and seemingly ruinous delays of Apocalypse Now (1979) – or ‘Apocalypse Later’, as it was snarkily dubbed while production in the Philippines ran on and on. Francis Ford Coppola – like Cameron after him on the similarly bad-press-plagued Titanic – was vindicated by his film’s wild success.

But this last laugh didn’t last long, as he would find out on his very next film, the incredibly costly One from the Heart (1981) – a case of the budget being reviewed and the film itself disappearing in a trice. Then came The Cotton Club (1984), a chaotic mess of a production in which he and producer Robert Evans were at constant loggerheads. This double whammy torpedoed Coppola’s stature for years as a big-budget film-maker, illustrating what reputational damage multiple flops can wreak.

Some bad press is insurmountable. During the Montana shoot on Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), an undercover journalist called Les Gapay went so far as to sneak on set as an extra, to confirm rumours of the absolute madness unfolding.1 When the film came out, scraping together the grosses of any studio executive’s worst nightmares, Cimino’s film became a byword for Hollywood’s most wasteful tendencies, and a convenient rebuke to the overblown importance of the auteur – a film to which studios could point forever more to justify playing it safe.

From then on, any film with a hefty price tag suddenly had a target on its back. Failures couldn’t avoid being publicised, even smirkily given Preface trophies. The Golden Raspberry Awards were inaugurated in 1981 – that rather juvenile institution purporting, as a kind of anti-Oscars, to celebrate the worst of everything Hollywood has to offer.

Duly nominated for Worst Picture in 1988, Elaine May’s uncertain comedy Ishtar (1987), pairing Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman as talentless lounge singers, had been bedevilled by media attention crowing that it was a wildly overpriced vanity project. Ditto Hudson Hawk (1991), the lead-footed Bruce Willis caper that won big, but only at the Razzies.

Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990) had already been dubbed ‘Kevin’s Gate’, and could easily have gone the same way, but proved everyone wrong, not only winning seven Oscars but making an extraordinary fortune for a three-hour-long, levity-free frontier western. But the nickname lingered, soon attaching itself to Waterworld instead – or ‘Fishtar’, if you prefer.

Studios now have a convenient burial plot for their most embarrassing product, which can be swiftly sold off to streaming services and thereby submerged with minimal public exposure. Such companies have no obligation to reveal stats on how many people are watching, say, Joe Wright’s The Woman in the Window (2021), a shambolic $40m thriller funded by Fox, originally to be released by Disney, delayed by Covid, and then dumped, three years after it was made, on Netflix.

Streaming berths...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Medienwissenschaft | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-38122-7 / 0571381227 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-38122-7 / 9780571381227 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich