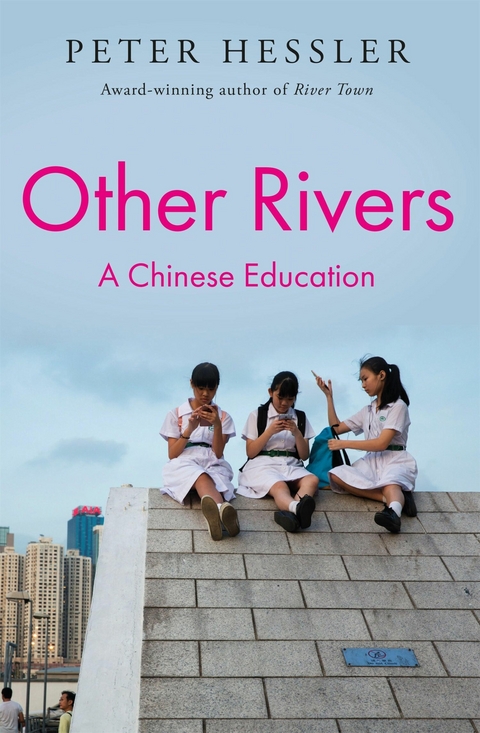

Other Rivers (eBook)

464 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-80546-287-3 (ISBN)

Peter Hessler is a staff writer at the New Yorker, where he served as Beijing correspondent from 2000-2007 and Cairo correspondent from 2011-2016. He is also a contributing writer for National Geographic. He is the author of River Town, which won the Kiriyama Book Prize, Oracle Bones, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, Country Driving, and Strange Stones. He won the 2008 National Magazine Award for excellence in reporting, and he was named a MacArthur fellow in 2011.

'Memorable... One of [China's] most astute and sensitive foreign observers' Financial Times'Compassionate... full of warmth' GuardianMore than twenty years after teaching English to China's first boom generation at a small college in Sichuan Province, Peter Hessler returned to teach the next generation. At the same time, Hessler's twin daughters became the only Westerners in a student body of about two thousand in their local primary school. Through reconnecting with his previous students now in their forties - members of China's "e;Reform generation"e; - and teaching his current undergraduates, Hessler is able to tell an intimately unique story about China's incredible transformation over the past quarter-century. In the late 1990s, almost all of Hessler's students were the first of their families to enrol in higher education, sons and daughters of subsistence farmers who could offer little guidance as their children entered a brand-new world. By 2019, when Hessler arrived at Sichuan University, he found a very different China and a new kind of student - an only child whose schooling was the object of intense focus from a much more ambitious and sophisticated cohort of parents. Hessler's new students have a sense of irony about the regime but mostly navigate its restrictions with equanimity, and embrace the astonishing new opportunities China's boom affords. But the pressures of this system of extreme 'meritocracy' at scale can be gruesome, even for much younger children, including his own daughters, who give him a first-hand view of raising a child in China. In Peter Hessler's hands, China's education system is the perfect vehicle for examining what's happened to the country, where it's going, and what we can learn from it. At a time when relations between the UK and China fracture, Other Rivers is a tremendous, indeed an essential gift, a work of enormous human empathy that rejects cheap stereotypes and shows us China from the inside out and the bottom up, using as a measuring stick this most universally relatable set of experiences. As both a window onto China and a distant mirror onto our own education system, Other Rivers is a classic, a book of tremendous value and compelling human interest.

Peter Hessler is a staff writer at the New Yorker, where he served as Beijing correspondent from 2000-2007 and Cairo correspondent from 2011-2016. He is also a contributing writer for National Geographic. He is the author of River Town, which won the Kiriyama Book Prize, Oracle Bones, which was a finalist for the National Book Award, Country Driving, and Strange Stones. He won the 2008 National Magazine Award for excellence in reporting, and he was named a MacArthur fellow in 2011.

CHAPTER ONE

Rejection

September 2019

THE VERY LAST THING THAT ANY TEACHER WANTS TO DO—AND the very first thing that I did at Sichuan University, even before I set foot on campus—is to inform students that they cannot take a class. Of course, some would say that rejection is a normal experience for young Chinese. From the start of elementary school, through a constant series of examinations, rankings, and cutoffs, children are trained to handle failure and disappointment. At a place like Sichuan University, it’s simply a matter of numbers: eighty-one million in the province, sixteen million in the city, seventy thousand at the university. Thirty spots in my classroom. The course title was Introduction to Journalism and Nonfiction, and I had chosen those words because, in addition to being simple and direct, they did not promise too much. Given China’s current political climate, I wasn’t sure what would be possible in such a class.

Some applicants considered the same issue. During the first semester that I taught, a literature major picked out one of the words in the title—nonfiction—and gave an introduction of her own:

In China, you will see a lot of things, but [often] you can’t say them. If you post something sensitive on social platforms, it will be deleted. . . . In many events, Non-Fiction description has disappeared. Although I am a student of literature, I don’t know how to express facts in words now.

Two years ago, on November 18th, 2017, a fire broke out in Beijing, killing 19 people. After the fire, the Beijing Municipal Government began a 40-day urban low-end population clean-up operation. At the same time, the “low-end population clean-up” became a forbidden word in China, and all Chinese media were not allowed to report it. I have not written an article related to this event, and it will always exist only in my memory.

As a student of Chinese literature, I have a hard time writing what I want to write because I am afraid what I write will probably be deleted.

Applicants handled this issue in different ways. I requested a writing sample in English, and most students sent papers that they had researched for other courses. Some titles suggested that the topics had been chosen because, by virtue of distance or obscurity, they were unlikely to be controversial: “Neoliberal Institutionalism in the Resolution of Yom Kippur War,” “The Motive of Life Writing for Aboriginal Women Writers in Australia.” Other students took the opposite approach, finding subjects close to home but following the government line; one applicant’s essay was titled “The Necessity of Internet Censorship.” There was also safety in ideology. A student from the College of Literature and Journalism submitted a Marxist interpretation of Madame Bovary. (“Capitalism has cleaned up the establishment of the old French society, and to some extent deconstructed various resistances that limit economic and social development.”) Another student abandoned every traditional subject—politics, business, culture, literature—and instead produced, in prose that was vaguely biblical, a five-hundred-word description of a pretty girl he had seen on campus:

She was a garden—her shoots are orchards of pomegranates, henna, saffron, calamus and cinnamon, frankincense and myrrh. She was a fountain in the garden—she was all the streams flowing from Lebanon, limpid and emerald, pacific and shimmering. . . .

My first impressions were literary: I saw the words before I met the students. Their English tended to be slightly formal, but it wasn’t stiff; there were moments of emotion and exuberance. Sometimes they made a comment that pushed against the establishment. (“I am still under eighteen years old now, living in an ivory tower isolated from the world outside. I’m expecting to change it.”) All of them were undergraduates, and for the most part they had been born around the turn of the millennium. They had been middle school students in 2012, when Xi Jinping had risen to become China’s leader. Since then, Xi had consolidated power to a degree not seen since the days of Mao Zedong, and in 2018, the constitution was changed to abolish term limits. These college students were members of the first generation to come of age in a system in which Xi could be leader for life.

The last time I had arrived in Sichuan as a teacher was in 1996, when Deng Xiaoping was still alive. While reading applications, I imagined how it would feel to return to the classroom, and I copied sentences that caught my eye:

Only when a nation knows its own history and recognizes its own culture can it gain identity.

Just as Sartre said, men are condemned to be free. We are left with too many choices to struggle with, yet little guidance.

Actually, all of us are like screws in a big machine, small but indispensable. Only when everyone works hard will our country have a brighter future.

The range of topics made it virtually impossible to compare applications, but I did my best. I had to limit the enrollment to thirty, which was already too many for an intensive writing course. After selecting the students, I sent a note to everybody else, inviting them to apply again the following semester. But one rejected girl showed up on the first day of class. She sat near the front, which may have been why I didn’t notice; I assumed that anybody trying to sneak in would position herself near the last row. At the end of the second week, when she sent a long email, I still had no idea who she was or what she looked like.

Dear teacher,

My name is Serena, an English major at Sichuan University, and I am writing in hope of your permission for me to attend, as an auditor, your Wednesday night class.

I failed to be selected. I have been in the class since the first week, and I sensed and figured my presence permissible.

I want to write. As Virginia Woolf thought, only life written is real life. I wish to be a skilled observer to present life or idealized images on paper, like resurrection or “in eternal lines to time thou growest.” . . . I started to appreciate writers’ diction not as a natural flow of expression but careful strategies and efforts, I began to put myself in the writers’ shoes, and set out to sharpen my ear as a way to hear the sound of writing—consonance or dissonance, jazz, chord, and finally symphony.

Perhaps I am being paranoid and no one will drag me out. If you can’t give me permission, I’ll still come to class in disguise until I am forced to leave.

Happy Mid-autumn Festival!

Thank you for your time.

Yours cordially,

Serena

I composed an email, explaining that I couldn’t accept auditors. But I hesitated before pressing “send.” I read Serena’s note once more, and then I erased my message. I wrote:

The college is concerned about auditing students, because the course needs to focus on those who are enrolled. But I much appreciate your enthusiasm, and I want to ask if you are willing to take the class as a full student, doing all of the coursework.

I was violating my own rules, but I sent the email anyway. It took her exactly three minutes to respond.

When I told other China specialists that I planned to return to Sichuan as a teacher, and that my wife, Leslie, and I hoped to enroll our daughters in a public school, some people responded: Why would you go back there now? Under Xi Jinping, there had been a steady tightening of the nation’s public life, and a number of activists and dissidents had been arrested. In Hong Kong, the Communist Party was reducing the former British colony’s already limited political freedoms. On the other side of the country, in the far western region of Xinjiang, the government was carrying out a policy of forced internment camps for more than a million Uighurs and other Muslim minorities. And all of this was happening against the backdrop of the Trump administration’s trade war against the People’s Republic.

It was different from the last time I had moved to Sichuan. In 1996, I knew virtually nothing about China, and almost all basic terms of my job were decided by somebody else. The Peace Corps sent me and another young volunteer, Adam Meier, to Fuling, a remote city at the juncture of the Yangtze and the Wu Rivers, in a region that would someday be partially flooded by the Three Gorges Dam. At the local teachers college, officials provided us with apartments, and they told us which classes to teach. I had no input on course titles or textbooks. The notion of selecting a class from student applications would have been unthinkable. Every course I taught was mandatory, and usually there were forty or fifty kids packed in the classroom. Most of my students had been born in 1974 or 1975, during the waning years of the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong’s reign.

In 1996, only one out of every twelve young Chinese was able to enter any kind of tertiary educational institution. Most of my Fuling students had been the first from their extended families to attend college, and in many cases their parents were illiterate. They typically had grown up on farms, which was true for the vast majority of Chinese. In 1974, the year many of my senior students were born, China’s population was 83 percent rural. By the mid-1990s, that percentage was falling fast, and my students were part of this change. During the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Schlagworte | angela hui • Anna Funder • Barbara Demick • Beryl Gilroy • black teacher • brothers sun • China • Cultural revolution • educated • Education • Geopolitics • Great Leap Forward • Hong Kong • jing tsu • Kate Clanchy • kingdom of characters • Meritocracy • New Cold War • nothing to envy • red memory • reform generation • Sichuan • Stasiland • Taiwan • Take away • tania branigan • tara westover • Teaching • technological revolution • Uighur • University |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80546-287-3 / 1805462873 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80546-287-3 / 9781805462873 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich