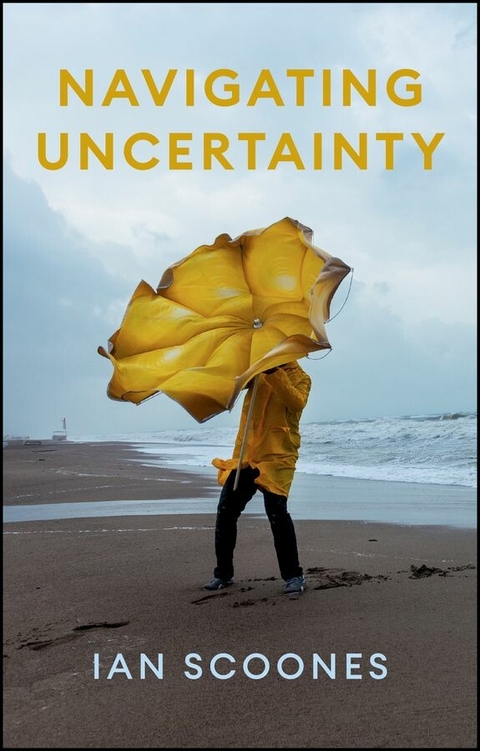

Navigating Uncertainty (eBook)

312 Seiten

Polity Press (Verlag)

978-1-5095-6009-7 (ISBN)

Drawing on experiences from across the world, the chapters in this book explore finance and banking, technology regulation, critical infrastructures, pandemics, natural disasters and climate change. Each chapter contrasts an approach centred on risk and control, where we assume we know about and can manage the future, with one that is more flexible, responding to uncertainty.

The book argues that we need to adjust our modernist, controlling view and to develop new approaches, including some reclaimed and adapted from previous times or different cultures. This requires a radical rethinking of policies, institutions and practices for successfully navigating uncertainties in an increasingly turbulent world.

Ian Scoones is a Professorial Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex.

Uncertainties are everywhere. Whether it s climate change, financial volatility, pandemic outbreaks or new technologies, we don t know what the future will hold. For many contemporary challenges, navigating uncertainty where we cannot predict what may happen is essential and, as the book explores, this is much more than just managing risk. But how is this done, and what can we learn from different contexts about responding to and living with uncertainty? Indeed, what might it mean to live from uncertainty?Drawing on experiences from across the world, the chapters in this book explore finance and banking, technology regulation, critical infrastructures, pandemics, natural disasters and climate change. Each chapter contrasts an approach centred on risk and control, where we assume we know about and can manage the future, with one that is more flexible, responding to uncertainty. The book argues that we need to adjust our modernist, controlling view and to develop new approaches, including some reclaimed and adapted from previous times or different cultures. This requires a radical rethinking of policies, institutions and practices for successfully navigating uncertainties in an increasingly turbulent world.

2

Finance: Real Markets as Complex Systems

It was the evening of Sunday, 14 September 2008, and employees of Lehman Brothers had heard about the imminent collapse of the investment bank. Over-exposed to sub-prime mortgage borrowing, its asset value had collapsed. Rumours spread that a Wall Street institution of over 150 years’ standing would be declared bankrupt the following day. Employees, some accompanied by family members, were in the smart metal-and-glass building in Manhattan collecting their personal belongings. The now famous images of bankers leaving the building clutching boxes, picture frames and pot plants are etched on our memories.

At the same time, in the Horn of Africa, pastoralist livestock brokers and traders, such as Mohamed Hassan from Moyale in northern Kenya, had long been involved in what, at face value, seems like a very different type of market. However, there are some important parallels. Livestock markets are cross-border, high volume and are subject to many uncertainties. Just like global financial markets, they are complex systems par excellence. In contrast to the deregulated markets that collapsed during the global financial crash, they are, however, much more embedded in local societies, governed by cultural norms and subject to continuous real-time negotiations, rather than relying on high-speed transactions and fancy algorithms. As we will see, this makes a big difference.

Lessons from the financial crash in 2007–8 are many, but an important theme described in this chapter is the importance of embedding financial and market networks in ways that allow for human interaction and effective reliability management in the face of market volatility. In order to respond to inevitable uncertainties in complex financial systems, heroic assumptions about the efficacy of models and regulatory hubris should be avoided. Moving beyond a positivist ‘economics of control’ promoted by a neoclassical vision of economics, there is instead a need to understand ‘real markets’, which are social, cultural and political, and thus the adaptive, improvised and practical ways that inevitable uncertainties can be navigated (De Alcantara 1992). The real markets of the pastoral rangelands offer some important lessons for thinking about complex financial markets everywhere, the chapter suggests, as we all must learn how to navigate the uncertainties generated by market volatility.

A complex, opaque and poorly regulated financial system

Through 2007 and 2008, the contagion of the financial crisis spread across the banking sector in the West, fuelled in particular by the sub-prime mortgage lending arrangements in the United States, where in the preceding years the value of unconventional, securitized mortgages was around US$1 trillion (Tooze 2018: 63). Banks collapsed, massive bailouts were offered and the knock-on consequences across economies were huge. Was this the beginning of the end of financialized capitalism or just a bump in the road? Was there a possibility of a last-minute rescue as with Bear Stearns bank only a few months before? We were living in a time of unprecedented financial uncertainty. Interviews with bankers on the streets of Manhattan and London the following day suggested few knew what was going on, but rumours were swirling. Asked by a news reporter what was happening in the building, one quipped ‘everyone’s using up credit on their canteen cards . . . We don’t know what’s going on.’1 The contagion that culminated in the crisis point was a long time in the making. It was the result of a long process of deregulation, from Margaret Thatcher’s ‘big bang’ in 1986 onwards. The consequence was a globalized financial system that was highly complex, opaque and poorly regulated (Tett 2009).

New financial instruments were devised to extract profit from the system from special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to credit default swaps (CDS), collateralized debt obligations (CDO), structural investment vehicles (SIVs), asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP), repo markets2 and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The bewildering array of acronyms and actors involved meant few understood the overall system and its dynamics. In individual banks and investment firms, people were trying to make money whichever way they could through a firm belief that they were able to manage risk and generate profit. The investment banks that later became household names – whether Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch or Morgan Stanley – perfected the art of managing the huge amounts of cash generated in the financial system through a range of derivative instruments, such as mortgage-backed securities. Here a bundle of mortgages or other debts is bought from banks and then traded, providing further funding for home buying as long as the underlying value of the asset is maintained.3 They are, in other words, ‘investments in investments, bets about bets’,4 which assume that the stock market behaves in predictable if random ways, without sudden, surprise ‘black swan’ events (Taleb 2007). This was a big error.

In the United States, the emergence of the sub-prime mortgage market fuelled a boom in home ownership and mortgage debt, backed by triple-A ratings as if these were assets literally as safe as houses. This in turn attracted more investors looking for safe assets in a volatile economy, trying to offset risks. Insurance companies entered the scene offering cover against highly risky assets, while some firms bought and sold financial products, such as mortgage-based securities, with no real assets behind them. Balance sheets were stacked with dodgy products, absorbing huge pools of cash on the money markets. The ‘shadow banking’ system was confusing and headed for disaster – a house of cards ready to collapse (Eggert 2008; Tooze 2018).

Yet few saw this coming. Confident statements were frequently offered by the leading lights of the global financial system. In May 2006, Ben Bernanke, recently appointed as chair of the Federal Reserve, highlighted the virtues of ‘financial innovation and improved risk management’, including ‘securitization, improved hedging instruments and strategies, more liquid markets, greater risk-based pricing, and the data collection and management systems needed to implement such innovations’. He argued that ‘these developments, on net, have provided significant benefits . . . Lenders and investors are better able to measure and manage risk; and, because of the dispersion of financial risks to those more willing and able to bear them, the economy and financial system are more resilient.’5 Similarly, in 2002, Alan Greenspan, Bernanke’s predecessor as Federal Reserve chair, commented approvingly of derivatives: ‘These increasingly complex financial instruments have been especial contributors . . . to the development of a far more flexible, efficient and resilient financial system.’6

When Raghuram Rajan – then chief economist at the International Monetary Fund and later governor of the Reserve Bank of India – presented a paper with a more sceptical and cautious tone at the celebration of Greenspan’s illustrious career at Jackson Hole in the summer of 2005, his comments were rejected out of hand (Tooze 2018: 67). His paper asked a simple question: ‘Has financial development made the world riskier?’ Exploring the growth of new financial instruments, he argued that the incentives for risk taking had increased within the financial system, potentially with dangerous consequences. It was a good question to pose, but the response was dismissed as backward looking and misguided. In retrospect the arrogant, hubristic complacency of the financial elite is extraordinary, but when you are overly confident that a risk-based regulatory system is firmly in place, uncertainties have the nasty habit of creeping up behind you and catching you by surprise, as they did only a few years later.

Models and mayhem

By the 2000s, financial systems were truly globalized. Everything and everyone was connected in a complex web. As the economic historian Adam Tooze explains in his celebrated book Crashed, understanding global finance was no longer a matter of looking simply at national accounts but the complex interconnection of large firms’ balance sheets linked across the world. Trade in increasingly complex financial products was occurring continuously, with billions of dollars being exchanged and transferred globally. The arrival of high-speed internet had made such transactions almost instantaneous, and the old-fashioned style of traders and brokers exchanging across the floor, over the phone or in a bar after work had long gone. Rapid, impersonal trades were the standard, guided by complex algorithms and carried out on computers connected internationally. CEOs, central banks and governments had little clue how everything worked, yet mistakenly trusted the system and the light-touch regulation while enjoying the profits.

At the centre of this complex web were mathematical models generating operational algorithms that were used to manage such interactions. In the period leading up to the crash, the now notorious Black–Scholes–Merton equation dominated the way financial interactions were understood, and a massive derivatives market based on options trading was created (MacKenzie and Spears 2014).7 As the mathematician Ian Stewart (2012) explains: ‘The Black–Scholes equation changed the world...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.7.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeine Soziologie |

| Schlagworte | Banking • Books about technology • climate change • critical infrastructures • Finance • future studies • governance of risk • known unknowns • natural disasters • pandemic management • Public Policy • Risk Management • Science Policy • Social Policy • Technology Policy • technology regulation • Uncertainty • unknown unknowns |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-6009-2 / 1509560092 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-6009-7 / 9781509560097 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 428 KB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich