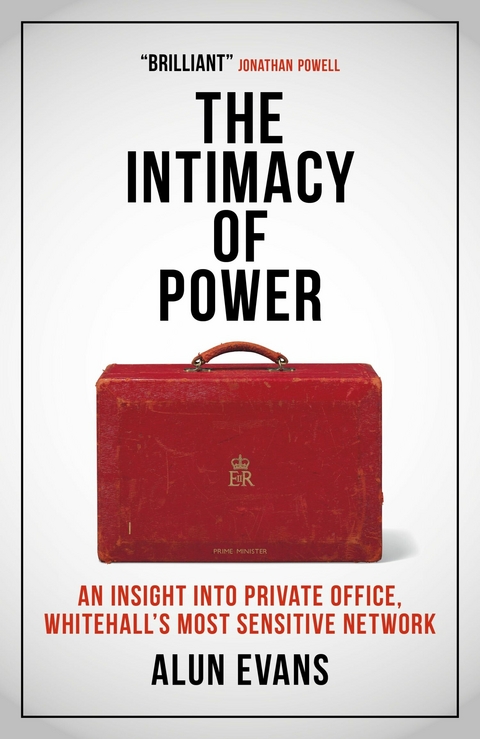

The Intimacy of Power: An insight into private office, Whitehall's most sensitive network (eBook)

432 Seiten

Biteback Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-78590-887-3 (ISBN)

Alun Evans is a political historian. For over thirty years, he was a UK civil servant. Between 1994 and 1998, he served as principal private secretary to three different Cabinet ministers. He subsequently worked at No. 10 for Prime Minister Tony Blair. His final government post was as head of the UK government office for Scotland at the time of the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence. From 2015 to 2019, he was chief executive of the British Academy, following which he completed his PhD on the history of private office. Since 2020, he has been a consultant on political strategy, devolution and communications. The Intimacy of Power is his first book.

Hi all,

After what has been an incredibly busy period, we thought it would be nice to make the most of this lovely weather and have some socially distanced drinks in the garden this evening.

Please join us from 6 p.m. and bring your own booze!

Martin.1

On 20 May 2020, at the height of the national lockdown – introduced by the Conservative government as part of its overall strategy for tackling the Covid pandemic – the above email was sent to all staff in No. 10, some 200 recipients, almost encouraging people to break the rules.

Many people might have assumed that the sender of this ‘Partygate’a email was the Prime Minister’s diary secretary, his office manager or even some kind of head butler in No. 10.

In fact, the author and sender of the email was Martin Reynolds,b the principal private secretary to Prime Minister Boris Johnson. Reynolds was then a senior diplomat of director general rank on secondment to No. 10. A graduate of Cambridge University, a former UK ambassador to Libya and a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George, he was the most senior civil servant in No. 10, and the private office which he headed represented a central plank of the machinery of UK government. Later, after the party had taken place with no journalists having picked up on this undoubtedly newsworthy story, Reynolds commented, ‘We seem to have got away with it.’2

Reynolds’s decision to take on the mundane task of issuing an invitation to drinks may have been an idiosyncratic one, but this action could easily have clouded the public’s perception of the role of the principal private secretary in No. 10. The work of the Prime Minister’s principal private secretary is not to be their social secretary but rather to manage the essential hub of support across the whole range of government activity, including advising on the appropriateness of events which the Prime Minister should attend. The job of the principal private secretary is also to run the equally prosaically titled ‘private office’.

But it is not at all surprising that the public at large do not understand the dated and often obscure language used in Westminster and Whitehall, which often appears to delight in obfuscation, especially where job titles are concerned. How can the person on the street be expected to understand the difference between a principal private secretary and a parliamentary private secretary (both of which are referred to as ‘PPS’), a permanent under-secretary of state or even a special adviser? What exactly do they each do? Certainly, some strange job titles exist elsewhere in many professions – deputy pro-vice-chancellor, suffragan bishop, house officer (in medicine), for example – but only Whitehall seems to revel and delight in obscurity, and the ministerial private office is a choice example.

Obscure language can be a barrier to understanding. What is private about the private office? And where is the office, if there is one – or is it virtual? If there is a principal private secretary, is there also a secondary or subordinate private secretary? Who appoints these people and how? How are they trained for the role and to whom are they accountable? Perhaps, most importantly, what do they actually do?

Private office is, in fact, an essential part of our system of constitutional democracy and the civil service that supports ministers, who are accountable to Parliament. It is the interface between the elected politicians, the permanent apparatus of government and the civil servants in the government departments of state. Yet, despite its importance, private office is little known or understood – and little considered – by the media and by most academic studies. This book aims to fill that gap and seeks to shed a light on private office, what it does and how it has changed throughout history.

How was it that, during Partygate, the most senior civil servant in No. 10, responsible for maintaining standards and the integrity of the office of the Prime Minister, ended up proposing a social event that would drive a coach and horses through the national guidance then applying to the activities of every citizen in the country? The 20 May party was not even a unique event. The subsequent report conducted by Sue Gray,c a senior civil servant in the Cabinet Office, identified sixteen such events that had taken place during the period of the Covid lockdown and that appeared to transgress the government’s own regulations. Why was the authority of private office apparently diluted to such an extent that there was no voice to question the legality, let alone the wisdom, of holding parties at the height of lockdown? Why was Reynolds – whose key responsibility was to advise the Prime Minister on issues of propriety and ethics – seemingly so lacking in fulfilling that duty?

The shortcomings in the leadership and management of the No. 10 private office in 2020 were, however, not so much a one-off aberration in standards but rather they reflected part of a longer-term trend. Indeed, some politicians have argued that the support functions for ministers are not fit for purpose and need to be less the preserve of the civil service. Some want a more muscular, or even a more politicised, private office. Such an approach inevitably risks bringing the civil service – an organisation founded on the principles of independence and non-party politicisation – into conflict with government. Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s principal private secretary – the head of his private office – appeared to be condoning, or even encouraging, rule-breaking. How had private office come to this?

This book explains what the ministerial private office is, what it does on a day-to-day basis and why it is so significant. Covering 200 years of political history, it highlights how the private office has played a prominent, if hidden, role in governance. It explores the vital role that some private secretaries have had at key events in British history, including how they interacted with ministers and political advisers. That great observer of the British constitution, Lord Hennessy, famously characterised the unseen elements that support the British political system as the ‘hidden wiring’ – by which he meant those structures, systems and people within, in particular, the civil service that collectively make the connections and ensure things happen smoothly, even though they themselves are usually invisible.3 If the civil service, as a whole, represents the totality of the ‘hidden wiring’ in Hennessy’s analysis, the private office represents the central junction box through which much political power and energy flows. Every minister, from the Prime Minister downwards, has a private office, whose job it is to ensure that business is transacted smoothly and efficiently, and yet usually out of sight of the media and the glare of publicity.

But, at times, the system has not always worked as seamlessly as it should. On occasion, the junction box has failed to make the right connections. This book traces the roots of the modern-day private office and its growth over the past two centuries, showing how it is now an established part of the hidden wiring and assessing the future of private office in the current political climate.

The title ‘private secretary’ and the functions of that role can be traced back some two centuries, although the term ‘private office’ is more recent. Originally, private secretaries were the officials attached to ministers and responsible for the conduct of managing ministerial business and ensuring the prompt receipt and despatch of ministerial business and correspondence. However, the modern-day private office plays a far more complex role than in the past. The role has, like that of ministers and Prime Ministers, expanded relentlessly. Today’s private secretary to an energetic minister may well assist in the process of policy-making, help facilitate cross-Whitehall organisation, liaise with the royal households, get involved in crisis management and help handle the media and communications, all on top of managing the day-to-day transactions of government. They (or a deputy) may find themselves on call for twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. A private secretary will accompany their minister to every official meeting.

Yet this role and the group of civil servants who work in private office have never been written about in detail. That is the gap which this book seeks to fill. Private secretaries are the characters who appear, sometimes only in passing, in biographies and memoirs; their roles have often been touched on but rarely in depth; and yet many ministers have testified as to how much they relied on them. Private secretaries have been, at times, some of the most powerful people in this country. Some have been colourful and controversial. Many have been brilliant minds and creative wordsmiths, well attuned to carrying out their political leaders’ wishes. Some have had close relationships with their ministers and have become immensely influential. In particular, those officials who have worked within the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | cabinet • Executive • Government • Politics |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78590-887-1 / 1785908871 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78590-887-3 / 9781785908873 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich