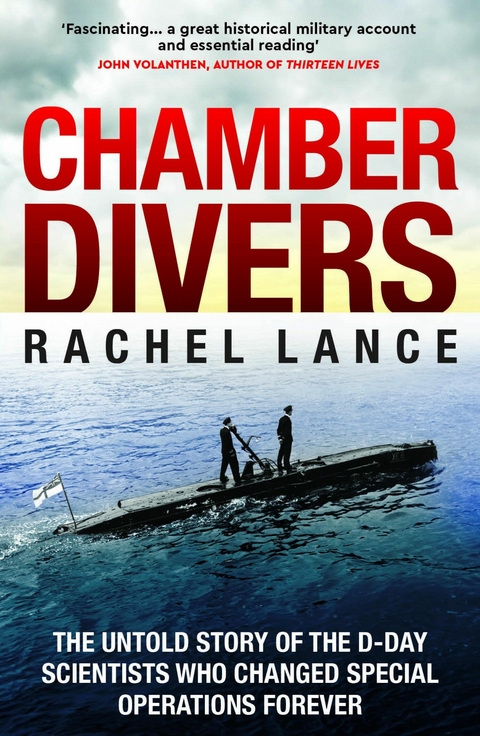

Chamber Divers (eBook)

448 Seiten

Bedford Square Publishers (Verlag)

978-1-83501-069-3 (ISBN)

Rachel Lance is an author and PhD biomedical engineer, specialising in trauma and survival in extreme environments. She began her career building underwater breathing systems for the US Navy, followed by researching problems of undersea physiology as faculty at Duke University. She now splits her time between scientific research and writing. A native of suburban Detroit, Michigan, Dr. Lance lives with her two pushy rescue mutts in Durham, North Carolina, where she enjoys scuba diving, baking, and properly designed O-ring seals.

'Fascinating...a great historical military account and essential reading' John Volanthen, author of Thirteen Lives. The untold story of the D-Day scientists who changed special operations forever. On the beaches of Normandy, two summers before D-Day, the Allies attempted an all but forgotten landing. Of the nearly seven thousand Allied troops sent ashore, only a few hundred survived the terrible massacre, and the reason for the debacle was a lack of reconnaissance. The shore turned out to be impassable to tanks. The Nazis had hidden obstacles in unexpected places. The fortifications were more numerous and deadly than imagined. The Allies knew they needed to take the fight to Hitler on the European mainland to end the war, but they could not afford to be unprepared again. A small group of eccentric researchers, experimenting on themselves from inside pressure tanks in the middle of the London air raids, explored the deadly science needed to enable the critical reconnaissance vessels and underwater breathing apparatuses that would enable the Allies' dramatic, history-making success during the next major beach landing: D-Day.

Rachel Lance is an author and PhD biomedical engineer, specialising in trauma and survival in extreme environments. She began her career building underwater breathing systems for the US Navy, followed by researching problems of undersea physiology as faculty at Duke University. She now splits her time between scientific research and writing. A native of suburban Detroit, Michigan, Dr. Lance lives with her two pushy rescue mutts in Durham, North Carolina, where she enjoys scuba diving, baking, and properly designed O-ring seals.

PROLOGUE

“A Piece of Cake”

DIEPPE, FRANCE

AUGUST 19, 1942

657 DAYS UNTIL D-DAY

The operation started with a simple cup of stew. By 0400, everyone had finished their hot, hearty breakfasts and begun to prep grenades. Thousands of warriors dressed in muted greens swayed with the rolling gray decks of the ships of the convoy beneath the meager light of the stars. Closer to the coast, the large ships split apart. The troops would attack at six separate locations.

Once nearer their location, British officer Captain Patrick Anthony Porteous helped his soldiers into position in the small, flat-bottomed boats that would take them the rest of the way. The propellers churned into motion. They headed for the chalky cliffs forming the dark skyline, a slight breeze from the stern nudging them landward.

The destination for Porteous’s group was a sloping, pebbly shore code-named “Orange Beach II,” located inside a curving hook of land in the northeast of Normandy, France. Their target cliffs tapered down to the west of the small resort town of Dieppe, and the other landing beaches—code-named “Yellow,” “Red,” “White,” “Green,” and “Blue”—lay to their left, in the east.

Porteous and his soldiers had watched tracer rounds briefly track across the skies during an unplanned encounter with armed trawlers during the Channel crossing, but the continued welcoming blink of a lighthouse onshore indicated that the scuffle had not triggered any alarms among the Germans. It was lucky because, for this group, that lighthouse was the primary means for navigation. They had limited maps, and no other visible beacons.

The Orange Beach party was divided into Groups I and II, and their joint objective sounded simple: silence the big guns in a reinforced artillery battery high on the cliff. If the battery was left intact, the German troops inside could lob mortar after gigantic, explosive mortar at the other five Allied beach locations, including the main landing sites. Group I would shimmy up a rain-carved gully in the cliff face and distract the enemy from the front. Group II would land to the west and sneak around behind. Porteous and his thirty soldiers, who formed half of F Troop of the British Number 4 Commando, had been designated part of Group II.

Captain Porteous had no idea what the true mission of the entire raid was. But like most soldiers, he knew that his role was not to reason why. His role was to destroy his assigned battery.

Group I landed without enemy opposition, guided in by the lighthouse. They used handheld tubes of explosives called Bangalore torpedoes to create a passageway up the cliff, blasting apart the thick nests of barbed wire that stuffed the narrow slot. A recent downpour had washed away the layer of dirt hiding most of the land mines, and under the moonless sky the soldiers picked their way over the safer patches of soil.

Group II was not as fortunate. As soon as Porteous and his commandos touched ground, the enemy opened fire. Machine guns tore through the night. Lightning-like bolts from tracer rounds showed that most bullets went above the commandos’ heads, but still they dashed across the pebbly shoreline.

To be trapped on an exposed, featureless beach was death. The longer the soldiers lingered without cover, the longer the Germans had to aim. The warriors of Number 4 Commando unfurled coils of chicken wire over the barbed wire blocking their exit from the beach, ran across these makeshift bridges, and dove down the steep drop on the far side. Somewhat protected in a small fold in the ground, they took a moment to regroup before proceeding inland.

No more than twenty of the two hundred in their party had fallen on the beach, fewer than predicted. A medic volunteered to stay behind, but the rest had strict orders: leave the dead and injured. Get off the beach, regardless of casualties, “regardless of anything.” They moved inland.

Group I’s gunfire from the front distracted the soldiers in the battery as hoped, while F Troop and the rest of Group II wound their way around, single file, silent, through a small passage in the hefty barbed wire guarding the back of the concrete monstrosity. Porteous and his troops lobbed explosives inside, killing the German soldiers and silencing their guns. Porteous was shot twice, once through the hand and once in the thigh, but he survived, as did most of Number 4. Their mission was a success.

However, theirs would be the only victory the Allies could claim that day in 1942. By the time Number 4 and their freshly taken German prisoners evacuated from the base of the cliff at 0815, with the wounded Captain Porteous in tow, they were faced with new horror. Thick layers of smoke obscured their view, but the raging thunder of machine guns and mortars at the other landing locations forced a brutal realization. Their compatriots were caught in the worst hell imaginable. Everyone else was stuck on their beaches.

Every snowball begins first as a harmless flake, a diminutive nucleus of crystallized water that, given a downhill nudge, quickly accumulates power. At Dieppe, one nudge was a case of mistaken identity.

In the dark, Gunboat 315 looked an awful lot like Gunboat 316. And by the time the Royal Regiment of Canada, headed for landing site Blue Beach, recognized the error and realigned behind the correct vessel, they were sixteen minutes behind schedule. The Royal Air Force had dropped a thick layer of smoke to obscure the aim of any Germans who happened to be awake, but by the time the tardy Royal Regiment arrived, the punctual smoke had begun to clear.

Aerial planning photographs taken months earlier had revealed the batteries gracing the tops of the cliffs, but the top-down views hadn’t hinted at the surprises in their vertical faces. The Royal Regiment landed on Blue amid the parting smoke and looked up to a nasty revelation. The shelling that had started on time at the other beaches had roused the Germans, and the Germans were not only awake; they had dug into the very cliffs themselves, creating machine-gun-filled nests burrowed into the sides of the steep white walls. They unleashed a furious thunderstorm of metal onto the Allies below.

The few Royals who survived the initial mad dash across the impossibly broad shore hunkered into small shapes, curled helpless against a meager seawall, hoping that the ships offshore and pilots in the air could take aim at the machine guns and mortars mowing them down. But it was hopeless. The officers on the ships couldn’t see through their own protective smoke screen. The pilots in the air, who were not equipped with rockets, struggled to hit the tiny targets dug into the cliff face with guns. Those down on the beach couldn’t fire upward and around corners into the machine-gun grottoes. Bullets and grenades peppered their sky.

Not a single soldier made it off Blue Beach. Almost half of the five hundred in the charge died. The unit had a casualty rate of 97 percent. But, since the Royal Regiment never got off the beach, they also never accomplished their goal: destroy the battery at the top of their cliff.

Other batteries in front of the main landing approach resisted Allied attack, too. In order to get to the town, the rest of the troops would have to run south across broad, open, unprotected beaches Red and White, with active guns crisscrossing their path. The deaths of the warriors at Blue, and the intact battery above them, were a snowball, and they triggered a crossfire avalanche. About a thousand of the Allied landing troops were British, but more than four-fifths of the 6,086 total were Canadians, with only about fifty Americans. What happened next is considered one of the most horrifying disasters in Canadian military history.

The inexperienced Canadian troops headed for Red and White were convinced that tanks alone would provide the power needed to break through the German defenses. Everyone would jump out of the ships together—the engineers with their packs full of explosives, the soldiers on foot, and the fearsome new tanks nicknamed “Churchills.” The soldiers would face down the guns while engineers blasted paths through the barriers blocking the exits from the beach; then the Churchill tanks would proceed smoothly and easily through those paths into the town. Their commander, General John Hamilton “Ham” Roberts, had even promised in his prelaunch pep talk that it would be “a piece of cake.”

An aerial photograph of the cliffs above Blue Beach, taken a few years after the raid. The gun caves are still visible in addition to the batteries along the top. (NARA photograph)

With this plan fixed in his mind, Dutch-born noncommissioned officer Laurens Pals of the 2nd Canadian, on board an impressive tank-carrying ship, confidently prepared to land on beaches Red and White. He did not know that the flanking batteries remained intact.

The barrage was instant, and staggering. The tanks had been waterproofed with a thin material, but their carrying vessels were not bulletproof. Both got riddled with projectiles. The vessels began to sink; the tanks began to swamp. Some coasted to land too crippled to function; others burbled to the bottom of the sea, drowning the people inside.

The process to unload the tanks was slow. The...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | alex kershaw • allied special operations • amphibious assault strategies • ben macintyre • british wartime • D-Day scientists • decompression sickness studies • evolution of diving equipment • Helen Fry • helen spurway • Historical account • hyperbaric chamber experiments • J. B. S Haldane biography • Key Historical Dates • military diving evolution • military science innovations • Military Technology • naval reconnaissance mission • Non-fiction • normandy invasion preparation • operation mincemeat • secret wartime experiments • The Longest Winter • underwater warfare • Untold story • War Stories • World War II |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83501-069-5 / 1835010695 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83501-069-3 / 9781835010693 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich