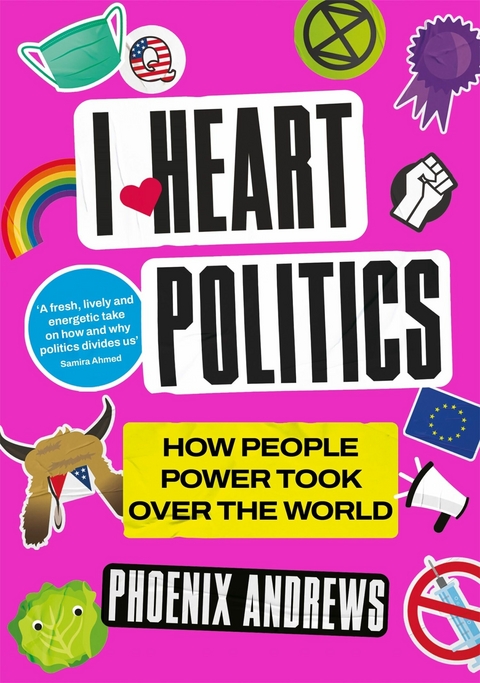

I Heart Politics (eBook)

288 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-423-9 (ISBN)

Phoenix Andrews is a journalist, writer, broadcaster and researcher. His expertise in politics, fandom, popular culture and digital culture has seen him published in The Times, Independent, Slate, Prospect, New Statesman and other publications, and interviewed by BBC World Service and Times Radio. He likes clothes too much, so much so that he started to make his own (badly).

Phoenix Andrews is a journalist, writer, broadcaster and researcher. His expertise in politics, fandom, popular culture and digital culture has seen him published in The Times, Independent, Slate, Prospect, New Statesman and other publications, and interviewed by BBC World Service and Times Radio. He likes clothes too much, so much so that he started to make his own (badly).

1

HISTORY

Fandom has always existed. Of course, it has changed over time. New technologies and the emergence of the ‘celebrity’ shaped the evolution of fandom, along with the media and politics, which have been intertwined for as long as they’ve existed. More people gained voting rights as access to information and campaigning abilities grew, at first through growing literacy and the printing press, later by broadcast media and the internet. From the populism of the ancient world to the memorabilia explosion of the twentieth century, history tells us a lot about politics fandom and how it became the phenomenon it is today.

The ancient world is where politics fandom began. Greek philosopher and historian Plutarch documented the Trump-like relationship between populist politician Clodius and his fans, whom he called ‘a rabble of the lewdest and most arrogant ruffians’. Clodius, while harassing the great Roman statesman Pompey (for planning to bring back his enemy, Cicero, from exile), stood in a prominent place and called out to the crowd:

‘Who is a licentious imperator?’

‘What man seeks for a man?’

‘Who scratches his head with one finger?’

And they, like a chorus trained in responsive song, as he shook his toga, would answer each question by shouting out ‘Pompey.’1

Much of the language of politics comes from the Greeks and Romans: ‘democracy’, ‘partisan’, ‘faction’. So too does the political myth. We never really know everything about a politician or political movement, and what we do know is heavily influenced by the stories they tell about themselves and those that are told about them. This kind of storytelling didn’t start with the modern media. Narrative and emotions drive voting patterns more than policy and principles, and likely have done since before someone scratched this message into a wall in Pompeii: ‘I ask that you elect Gaius Iulius Polybius as aedile. He bakes good bread.’2 Many people aren’t that interested in politics or its players in the time between elections, but political fans both keep political myths alive and even develop them.

Perhaps the most beloved figure in political history is Pericles, the great ancient Athenian orator and statesman, who has been cited as inspirational to politicians past and present. But why is he so admired, by Hitler and Boris Johnson alike? Perhaps because historians are fans, too – and they themselves have fans, who support their authority as experts. History is shaped by the people who write and share it. Their choices of what information to include in their writing and how they frame the facts persuade us, intentionally or not, to view politicians as heroes or villains.

In the case of Pericles, his reputation comes from ancient Greek historian Thucydides. Thucydides himself has modern-day fans and is still widely studied because he writes insightfully about politics, social behaviour and communication. He also rewrote accounts of historical figures to make them appear more noble and articulate. Pericles’ most famous speech is the Funeral Oration (given after a battle, not at an actual funeral), which Thucydides recounted from his own memory and that of others. It is likely not a verbatim transcript, but rather an attempt to capture a sense of Pericles’ ideas and ideals and an invitation to readers to compare the vision Pericles outlined in his speech with the reality of the period.

The following excerpt from the opening of the Funeral Oration shows that the speech was eloquent and admirable, and it made fans of many who love politics and democracy:

Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighbouring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favours the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.3

But how much of this writing is a true reflection of Pericles, and how much is myth created by a fanboy and excellent writer?

Beyond grand battles and noble speeches, things got messier when the general public started to become involved in politics. There were no elections in the Byzantine Empire, which was the continuation of the Roman Empire in eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Curiae, or city councils, usually only appointed the wealthy landowning elite. Ordinary people could only voice their opinions on social and political issues through shouting and booing at public events. Well-organized fan clubs (demes) that supported sports factions or teams (‘faction’ comes from factione, the name for a company of charioteers) were the main outlet for their enthusiasms and frustrations, acting like a mixture of football hooligan gangs and political parties. Sports and politics have long been linked, from chariot racing fans booing the emperor at the Hippodrome in Constantinople to Liverpool fans cheering the death of Margaret Thatcher. The name for a fan of a faction? Partisan, a word often used as a slur in modern politics for those seen as mindlessly tribal. The emperor and his officials looked out for signs of public unrest across the Byzantine Empire, which often flared up among the partisans at chariot races. Fans shouted their political demands between races. The imperial forces and guards in the city needed the co-operation of the factions to maintain law and order.

There were initially four major factions in chariot racing, named for the colours of charioteers’ uniforms. These were the Blues (Veneti), the Greens (Prasini), the Reds (Russati) and the Whites (Albati). Fans wore their faction’s colours. By the sixth century the only teams with any influence were the Blues and Greens, and that’s when things got spicy. The Nika Riots against Emperor Justinian took place in Constantinople during one week in ad 532.4 Nearly half of Constantinople was burned or destroyed, and tens of thousands of people were killed.

It began with a fight that broke out during a chariot racing event at the Hippodrome. The fight was between fans of the Blues and Greens. It ended badly, and seven partisans involved in the violence were found guilty of murder. However, one Green and one Blue fan escaped hanging because the scaffold holding the noose broke, and they sought sanctuary in a church. The crowd who were watching the hanging called upon the emperor to pardon the pair. But Emperor Justinian didn’t give in to their request and refused to respond to the demands, so a riot kicked off.

By the time there were only two races left of the season Justinian still refused to respond, and the factions united to oppose him. It didn’t matter who they supported; it mattered that they, as fans, won. Partisans stopped yelling ‘Blue!’ or ‘Green!’ and started chanting ‘Nika!’: the ‘Victory!’ chant. Justinian still wouldn’t respond to partisan demands at the Hippodrome, so they burned down the praetorium and the crowd freed the prisoners. The emperor tried to restart the games, but the partisans set fire to the Hippodrome itself and demanded three officials were fired. Justinian finally responded by dismissing the officials, but then he sent in troops to try to stop the partisans.

The partisans set alight more civic buildings; Justinian sent in more troops from the garrison. He eventually suppressed the riot. Much of the violence and unrest may have been avoided if Justinian (a fan of the Blues) had understood how far the partisans were prepared to go and if the public had more of a voice in local and imperial politics.

The next snapshot of history I want to explore involves a technological development that changed fandom and politics forever, so we will have to travel forwards about a thousand years. Charles Babbage, the mathematician credited with inventing the computer, reportedly said that ‘the modern world commences with the printing press’. With the printing press, literacy and learning became available to ordinary people. They also now had an affordable and widely available method to read and express political views: the pamphlet. These printed tracts were used to argue points of religious doctrine, report news and express political dissent. By the 1580s, during the Reformation period, pamphlets had begun to replace broadsheet ballads as the main means for communicating information to and influencing the views of the general public. The printing press also made it possible to be a fan nationally and internationally. Pamphlets were very much the social media of their time, with interpersonal complaints playing out as well as ideas spreading between their pages. Thus began what became known as the ‘pamphlet wars’.5 6

During this time, both Protestants and Catholics engaged in the pamphlet wars, which might be viewed as the first battle for the popular mind in Western history. Now that’s politics. People often draw a parallel between fandom and religious fervour, and associate popular political figures with a cult of personality. The Reformation saw what might be called the first battle for the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.4.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie | |

| Schlagworte | Boris Johnson • Brexit • Capitol Hill Riots • Demo • Democracy • Division • Donald Trump • Extinction Rebellion • Fandom • Fans • fbpe • i'm a celebrity • Jeremy Corbyn • lettuce • Liz Truss • March • Marie Le Conte • milifandom • Nigel Farage • Polarisation • Politics • Populism • Protest • Qanon • UK politics |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-423-6 / 1838954236 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-423-9 / 9781838954239 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich