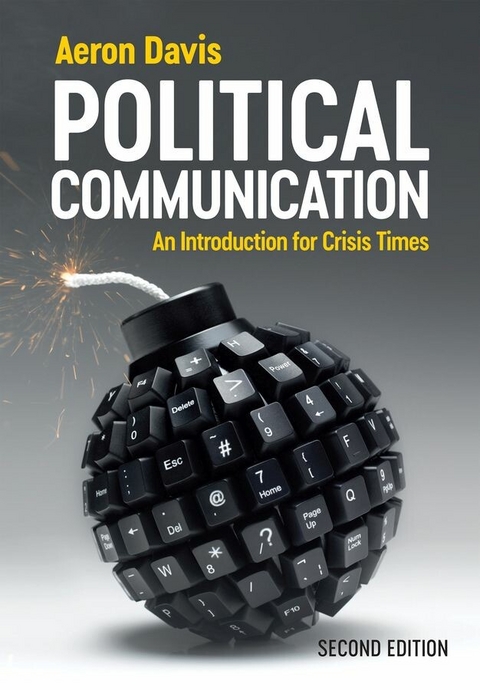

Political Communication (eBook)

228 Seiten

Polity Press (Verlag)

978-1-5095-5706-6 (ISBN)

This second edition of Political Communication bridges old and new to map the political and cultural shifts and analyse what they mean for our ageing democracies. With new sections and revisions to all chapters, the book continues both to introduce and challenge the established literature. It revisits key questions such as: Why are polarized electorates no longer prepared to support established political parties? Why are large parts of the legacy media either dying or dismissed as 'fake news'? And why do some democratic leaders look more like dictators? In this fully updated edition, there is greater focus on digital developments, and it is enriched with new global comparisons and useful ancillary material.

Political Communication: An Introduction for Crisis Times will appeal to advanced students and scholars of political communication, as well as anyone trying to understand the precarious state of today's media and political landscape.

Aeron Davis is Professor of Political Communication at Victoria University of Wellington.

We are living in a period of great uncertainty. The rise of extreme populists, economic shocks and rising international tensions is not only causing turmoil but is also a sign that many long-predicted tipping points in media and politics have now been reached. Such changes have worrying implications for democracies everywhere.This second edition of Political Communication bridges old and new to map the political and cultural shifts and analyse what they mean for our ageing democracies. With new sections and revisions to all chapters, the book continues both to introduce and challenge the established literature. It revisits key questions such as: Why are polarized electorates no longer prepared to support established political parties? Why are large parts of the legacy media either dying or dismissed as 'fake news'? And why do some democratic leaders look more like dictators? In this fully updated edition, there is greater focus on digital developments, and it is enriched with new global comparisons and useful ancillary material.Political Communication: An Introduction for Crisis Times will appeal to advanced students and scholars of political communication, as well as anyone trying to understand the precarious state of today's media and political landscape.

Aeron Davis is Professor of Political Communication at Victoria University of Wellington.

Foreword to the Second Edition and Acknowledgements

Part I: Introductory Frameworks

1. Introducing Political Communication in Crisis Times

2. Evaluating Democratic Politics and Communication

3. Digital Media and Political Communication

Part II: Institutional Politics and Legacy News Media

4. Political Parties and Elections

5. Political Reporting and the Future of (Fake) News

6. Media-Source Relations, Mediatization and Populist Turn in News and Politics

Part III: Citizens and Organised Interests Beyond the Political Centre

7. Citizens, Media Effects and Public Participation

8. Civil Society, Powerful Interests and the Policy Process

9. Interest Groups, Social Movements and Campaigning for Equality and the Environment

10. Globalisation, the State and International Political Communication

11. Conclusions: Post-Truth, Post-Public Sphere and Post-Democracy

Bibliography

Index

'In a time characterized by numerous simultaneous crises, transformative changes and democratic backsliding, this well-written and highly insightful book can be recommended to anyone interested in contemporary political communication and the fate of democracy.'

Jesper Strömbäck, University of Gothenburg

'Political Communication arrives at a time of rapid change and deepening crisis in democratic societies. It provides an engaging, magisterial and rigorous assessment of the impact of recent transformations - ranging from the rise of authoritarian populist leaders to the Covid-19 pandemic. The book is a must-read for anyone who wants to make sense of political communication in unprecedented times.'

Karin Wahl-Jorgensen, Cardiff University

2

Evaluating Democratic Politics and Communication

What does it mean for democracy when its champion – ‘the leader of the free world’ – loses its democratic heart? This is what seemed to be signalled when, on 6 January 2022, a large mob of Trump supporters broke into the Capitol Building and ran amok. For many critics, the world’s most powerful nation has displayed all manner of democratic failings over the years. But this was something else. Donald Trump and his advisors were attempting to use their power to overturn a free and fair election, if not through legal means, then by force.

In some ways, the erosion of democracy in the US is not such a surprise. It is currently classed as a ‘flawed democracy’ by the Economist Intelligence Unit (2021), behind much poorer, smaller and newer democracies like Chile and Costa Rica. But it does make us wonder how exactly does one evaluate what makes for a ‘good’ democracy and a ‘healthy’ political communication system? On what basis are countries like Norway, New Zealand and Taiwan regarded as exemplary models, while others, like Brazil, India and Singapore, are considered quite ‘flawed’?

Understanding what norms, ideals, institutions and practices make for a strong, stable democracy is important for a few reasons. For one, we need a framework for evaluating what we have. Second, a set of markers aids us in making judgements about whether and to what degree our democracy is in crisis. Third, such discussions help identify the range of alternatives on offer, enabling debates about what changes might be adopted in future.

This chapter attempts to do this with a presentation of three related literatures and discussions. The first of these returns to first principles by outlining the basic philosophy and ideals of democracy as they relate specifically to media and communication. In particular, the focus is on general notions of Liberty, Equality and Society. The second literature is that which has built upon Jürgen Habermas’s historical account of the public sphere, its associated ideals and varied modern equivalents. The third area is comparative systems work in politics and communication, a line of research that has expanded considerably in the last two decades.

Although these literatures are distinct, they share a set of norms, values and tensions, each of which sits at the heart of both old and new debates about democracy and communication. These move through abstract notions of what makes for ‘good’ democracy to discussions of systems and institutions, to more concrete evaluations of what Nancy Fraser (1997) calls ‘actually existing democracies’.

Public Communication Ideals and Representative Democracy

Democracy’s History and Philosophy

Democracy developed historically in opposition to more autocratic forms of rule. The concept of democracy came from the ancient Greeks and literally means ‘the rule of the citizen body’. Athenian democracy was practised in some city-states as an alternative to tyrannical rule. That said, participation still excluded the majority, and forms of democracy were limited and usually short-lived.

Similar oppositions to tyranny developed later in Europe’s early modern period. Rule was directed by the ‘divine right of kings’, aided by the nobility and Church. This became increasingly challenged by parliaments, civil wars and the emerging bourgeoisie. A common set of liberal ideals, involving the participation, rights and responsibilities of individuals and the citizen body, was developed in philosophical treatises. Direct confrontations with English monarchs such as James II in 1689, the US overthrow of British rule in 1776, and the French Revolution of 1789, all produced new declarations and bills of rights. Each of these contributed to transforming ideals into codified constitutions, law and democratic institutions. In turn, such elements were frequently adopted by emerging democracies through the twentieth century as well as in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They are still central, even as their interpretation has become more contested and their application ever more complicated (see Ball and Dagger, 2004; Held, 2006, for an overview).

The larger role of public communication in relation to such democratic ideals was often omitted, or a secondary consideration. Little was set down much beyond the insistence on freedom of speech and of the press, as contained in the US First Amendment. But, for some key thinkers in earlier centuries (e.g., Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill, Jeremy Bentham), it was an important element to which they paid attention in their writing. They themselves benefited from the rise of mass printing and the dissemination of new ideas through political pamphlets and newspapers. Accordingly, they looked to print media as an important component of new, more democratic polities (see Keane’s overview, 1991).

Some of their twentieth-century counterparts (e.g., Walter Lippmann, John Dewey, Jürgen Habermas) pondered the importance of public communication too and added broadcast media into the mix. Current day thinkers wrestle with the additional mediums of the internet, social media and mobile communication. Clearly, whatever the predominant modes of public communication, it is essential for a number of core operating features of democracy. The ways that a state establishes legitimate public authority, how citizens become informed about issues and electoral candidates, how those in charge are held accountable, and how individuals get a wider hearing for their concerns, all require widely shared, reliable and accessible forms of communication. Accordingly, a set of normative ‘ideal’ media and public communication functions in democracies has emerged (see Keane, 1991; Norris, 2000; Curran, 2002, for discussions).

Democracy’s Core Ideals

What are these core ideals and how do they apply to public communication in democracies? Three core concepts come up in virtually every treatise or declaration of rights: Liberty, Equality and some sense of binding nationhood. They are most simply summed up in the motto of the 1789 French Revolution, enshrined in the constitutions of later French Republics, as ‘Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité’. To put it a little simply, Liberty, Equality and Fraternity/Sorority (or a sense of nationhood) are the equivalent of democracy’s primary colours.

All three concepts have varied interpretations and applications in democratic theory. Liberty initially referred to physical freedom of the individual (contested in past eras of colonialism and slavery), and also to the need to be free from the coercion of monarchs and all-powerful states. But it also came to be interpreted as freedom to participate politically, and freedom of action and opinion. Equality put all individuals on the same standing, declaring everyone was born equal, and therefore should have equal rights to free speech, religious affiliation, property and so on. But what else should be included here is debatable. Health, education, minimal levels of shelter and food are all considered vital to guarantee ‘equality of opportunity’ in some nations but not others. And, of course, all societies produce multiple inequalities to varying degrees.

Sororities/Fraternities (not the kind in US colleges) of necessity demarcate who is to be included, be it on the national, regional or other level. Those ‘citizens’ who are, make up the general will, contribute to the public good, and have obligations as well as rights. Pretty much every form of democratic citizen body, from the past to now, has had its exclusions denoted by a combination of gender, race, property, religion, wealth, official citizenship, legal freedom, age and so on. But this sense of society and inclusion is also connected to a set of cultural norms and values and a notion of national identity.

In relation to public communication, these core ideals are typically interpreted in the following ways. Under liberty, the media has a role to play to support individual liberties and freedom of speech by keeping governments and their leaders in check, holding them up to public scrutiny and exposing abuses of power. Thus, mainstream news media take on a ‘watch-dog role’ and have been regarded as the ‘fourth estate’ (government, parliament and judiciary making up the first three). Equality translates to equal access to information and to expression of opinion. As democracies advance, so many argue that the maximum amount of citizens possible may be informed about and be able to intervene in debates that affect them. A healthy democracy contains a plurality of opinions from different peoples, parties, organizations and institutions. In relation to sorority or nationhood, there is the general sense of public media, culture and communication pulling all citizens together. Political and media systems provide the shared communicative architecture that holds democratic, consensual nation states together. They offer shared platforms for information circulation, deliberation and debate, allowing national participation.

These basic ideals are fairly easy to agree on. Historically and in the present, democracies are concerned with balancing the elements of liberty, equality and nationhood. It is rare to find a politician or newspaper editor in democracies arguing outright against any of them. Even more extreme right-wing populists and radical...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Aeron Davis • Communication • Communication & Media Studies • Communication Studies • Democracy • Kommunikation i. d. Politik • Kommunikationswissenschaft • Kommunikation u. Medienforschung • Mass media • media • Media Studies • Medienforschung • political communication • Politics • Propaganda • Public Communication • Social Media |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-5706-7 / 1509557067 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-5706-6 / 9781509557066 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich