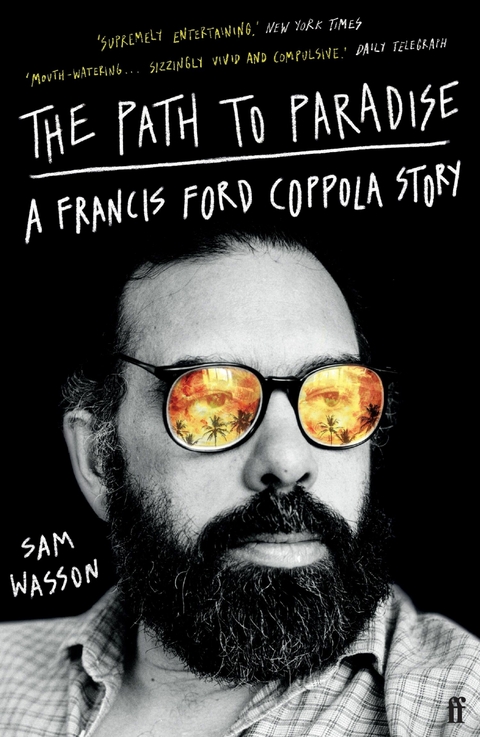

Path to Paradise (eBook)

384 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-37986-6 (ISBN)

Sam Wasson studied film at Wesleyan University and at the USC School of Cinematic Arts. He is the author of the bestseller Fifth Avenue, 5A.M.: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany's and the Dawn of the Modern Woman. He is also the author of the definitive biography of dancer-choreographer-filmmaker Bob Fosse. He currently teaches film at Emerson College in Los Angeles.

Say 'Coppola' and The Godfather immediately comes to mind. But Coppola isn't Corleone -- he's more than that. He's a visionary who predicted that digital cameras - no larger than one's hand - would allow anyone to make movies. And then set up a studio, Zeotrope, to make his dreams a reality. The book presents the highs and lows of both his personal and professional life, as Coppola sets out to transform the process of making movies. Sam Wasson masterly captures the larger-than-life figure of a man who pursued a vision of the world of movies and all the wonder of what that would be.

In this life, he has made and remade movies, won and lost Oscars, won and lost millions, fathered children and grandfathered grandchildren, a great-grandson, lost a son. He has built temples, bombed temples, grown grapes, grown a beard, stomped grapes, shaved his beard. He has written and discarded drafts, completed and then recut movies, fought the studios, battled the current of the times, won battles, lost battles, lost his mind. He has created a filmmaking empire, a hospitality empire, made hell, made paradise, lost paradise, and dreamed again.

“I am vicino-morte,”2 he said recently, turning from his current draft of Megalopolis. “Do you know what that means?”

“Morte … I know morte …”

“Vicino … it means ‘in the vicinity of’ …”

*

He keeps changing. They say you only live once. But most of us don’t live even once. Francis Ford Coppola has lived over and over again.

In the natural world we all know, he has been, like many of us will be, a child who became old and will die. But in his life as a filmmaker, he lives in new worlds of his own imagining, each a laboratory for his, and others’, re-creation. Beginning with his 1966 feature, aptly titled You’re a Big Boy Now, Francis Ford Coppola initiated a colossal, lifelong project of experimental self-creation few filmmakers can afford—emotionally, financially—and none but he has undertaken. Through the artistic and social ingenuity of his company Zoetrope—in Greek, “life revolution”—his living, dying, living production company and onetime studio, he has marshaled the stubbornly earthbound resources of filmmaking, business, technology, and the natural world to stage—and that’s what his Zoetrope laboratory is, a stage—literal worlds analogous to those of whatever characters he’s creating. As he famously said of Apocalypse Now, the paragon of Zoetrope-style filmmaking, he made a war to film war: “My technique for making film is to turn the filmmaking experience,3 as close as I can, into the experience of [whatever] fiction we’re dealing with.”

Creating the experience. The experience that re-creates the self. The re-created self that creates the work. These are the life revolutions of Zoetrope. They are what this book is about. How Francis Ford Coppola, leader, driving force of Zoetrope, sacrificed more than the normal man’s share to improve the world, the lives of the people in it, one filmmaking community at a time.

As no other filmmaker does, Coppola lives in his stories, changing them as they change him, riding round an unending loop of experience and creation, until either the production clock strikes midnight and the process must stop or, one hopes, he recognizes his new self in the mirror of the movie—for him,4 a documentary of his new internal landscape—and cries, “That’s it! I got it! Now that I know this part of myself, I know what the movie is!”

Sometimes, though, he never gets there. It never gets there.

And on a few occasions, he and the movie end up tragically far away.

But artistic perfection has never been integral to Coppola’s colossal experiment. Learning and growing have been. Living is. Dying is.

The adventure is.

*

August in Napa Valley. Lunchtime at Zoetrope, a world apart from the world. But not a dream.

Masa Tsuyuki was vigorously stirring a pan of leftover pasta, talking about the egg, the egg, the added egg, almost singing of its power to transform yesterday’s lunch into today’s delicious something …

Just outside, through the wide-open doors of the kitchen, two apprentices laded twenty feet of picnic table with plums and berries and summer salad and a cobbler someone brought from home. Gazing at the spread in disbelief, a studious-looking fellow paused at the top of the stairway leading down from the library. Wiping his eyeglasses, he volunteered to help, and was laughingly commanded, by Masa, to sit down and eat. He introduced himself to one of the apprentices—Dean Sherriff, artist, brought up to assist Coppola on the visual conceptualization for Megalopolis.

Megalopolis is the story—soon to be filmed—Coppola has been thinking about, quarreling with, adding to, altering, and rediscovering for forty years.

Forty years. The story keeps changing.

Coppola keeps changing. His work keeps changing. The Godfather he made in a classical style; Apocalypse Now opened him to the surreal; One from the Heart, he says, he made in a theatrical mode, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula he built, as an antiquarian, with the live effects of early cinema. But what was his style? With Megalopolis—sixty years after his first feature—Coppola would at last find out.

In preparation for the shoot, Masa, when he isn’t preparing lunch, is rewiring “the Silverfish,” Coppola’s forty-year-old bespoke mobile cinema unit. Anahid Nazarian, right-hand woman for forty years, is on the phone, ten to five, making sure everything they are going to need will be at the studio in Peachtree City, Georgia, before they need it. Now Anahid sits restfully, eyes closed against the sun. Behind her, a fireworks explosion of orange and gold lantana shoots up the stone wall of the Zoetrope library, once a carriage house. Perched on a garden box at Anahid’s feet, a butterfly alights on a zucchini blossom and then flies off.

“Ready!”5 Masa cries. “Everybody sit!”

Megalopolis is a story of a utopia, a story as visionary and uncompromising as its author; more expensive, more urgently personal than anything he has ever done; and for all these reasons and too many others, nearly impossible to get made. In the eighties, when Coppola, felled with debt after Zoetrope’s second apocalypse—the death of Zoetrope Studios in Los Angeles—was directing for money, he read the story of Catiline in Twelve Against the Gods, tales of great figures of history who, Coppola said, “went against the current of the times.” Catiline, Roman soldier and politician, had failed to remake ancient Rome. There was something there for Coppola. Something of himself. What if Catiline, Coppola asked himself, who history said was the loser, had in fact had a vision of the Republic that was actually better? Throughout the decades, he’d steal away with Megalopolis, a mistress, a dream, gathering research, news items, political cartoons, adding to his notebooks—in hotels and on airplanes and in his bungalow office in Napa—glimpses of an original story, shades of The Fountainhead and The Master Builder braced with history, philosophy, biography, literature, music, theater, science, architecture, half a lifetime’s worth of learning and imagination. But Coppola wasn’t just writing a story; he was creating a city, the city of the title, the perfect place. Refined by his own real-life experiments with Zoetrope, his utopia, Megalopolis would be characterized by ritual, celebration, and personal improvement, and driven by creativity; it had to be. Corporate and political interests, he had learned too well, were driven mainly by greed. And greed destroyed.

Over the years, Megalopolis grew characters, matured into a screenplay, tried to live as a radio drama and a novel, and for decades wandered like the Ancient Mariner, telling its story, looking for financing, or a star: De Niro, Paul Newman, Russell Crowe … The story of Coppola’s story became a fairy tale for film students, a punch line for agents … and in 2001, paid for with revenues from his winery, it almost became a movie. On location in New York City, Coppola shot thirty-six hours of second-unit material. But after September 11, he halted production. The world had changed suddenly,6 and he needed time to change with it.

He passed the script to Wendy Doniger, University of Chicago professor of comparative mythology (and years before, his first kiss). She introduced Coppola to the work of Mircea Eliade—specifically, his novel Youth Without Youth, the story of a scholar who is unable to complete his life’s work; then he is struck dead by lightning and rejuvenated to live and work again. Coppola, rejuvenated, made a movie from it. It was his first film in a decade. Thinking like a film student again, he kept making movies—Tetro in 2009; Twixt, 2011—modest in size and budget, fearing that Megalopolis, a metaphysical, DeMille-size epic, was and always would be a dream only, beyond his or anyone’s reach. Utopia, after all, means a place that doesn’t exist.

Then he decided to finance the picture himself, for around $100 million of his own money.

*

Coppola appeared at the picnic table. He was reading.

Around him, Zoetropers bustled into and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Medienwissenschaft | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-37986-9 / 0571379869 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-37986-6 / 9780571379866 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich