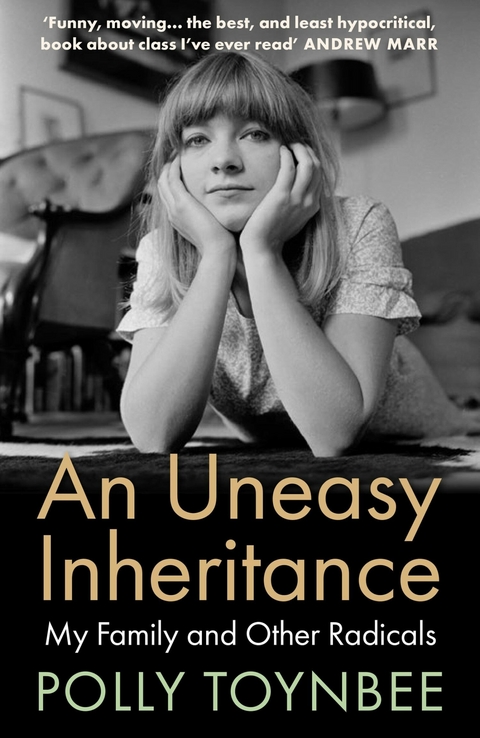

An Uneasy Inheritance (eBook)

448 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-836-7 (ISBN)

Polly Toynbee is a journalist, author and broadcaster. A Guardian columnist and broadcaster, she was formerly the BBC's social affairs editor. She has written for the Observer, the Independent and Radio Times and been an editor at the Washington Monthly. She has won numerous awards including a National Press Award and the Orwell Prize for Journalism.

Polly Toynbee is a journalist, author and broadcaster. A Guardian columnist and broadcaster, she was formerly the BBC's social affairs editor. She has written for the Observer, the Independent and Radio Times and been an editor at the Washington Monthly. She has won numerous awards including a National Press Award and the Orwell Prize for Journalism.

1

What Children Know

CHILDREN KNOW. THEY breathe it in early, for there’s no unknowing the difference between nannies, cleaners, below stairs people and the family upstairs. Children are the go-betweens, one foot in each world, and yet they know very well from the earliest age where they belong, where their destiny lies or, to put it crudely, who pays whom. From a young age their loyalties are torn, betrayal of both inevitable, colluding in complaints with gossip passing each way, upstairs and down. Every autobiography, every story about middle class childhood is riddled with guilt, complicity and awareness. Love that nanny, au pair, housekeeper or any paid employee – but never forever. Never equally. Tiny hands are steeped young in the essence of class and caste.

In their first view from the pushchair, they know as ineffably as they know about male and female how others compare, who fits, who’s the same, who’s different. No one need speak a word. Good liberal parents will strain every nerve to deny it’s there, to blank it out and protect their offspring from the awkward truth of their lucky lives, but the harder they pretend, the more a child sees and knows. In nursery school, in reception they see the Harry Potter sorting hat at work. They know. And all through school those fine gradations grow clearer, more precise, more consciously knowing, more shaming, more frightening. Good liberal parents teach their children to check their privilege – useful modern phrase – but it swells up like a bubo on the nose. There’s no hiding it.

Maureen

I can summon up the childhood shame at class embarrassments. Aged seven like me, Maureen, with her hair pinned sideways in a pink slide, lived in a pebble-dashed council house in the Lindsey Tye, the small row by the water tower. They lived at the other end of Lindsey, more hamlet than village, half a mile down the road from my father’s pink thatched cottage set in the flat prairie lands of Suffolk. I envied Maureen for what looked to me like a cheerful large family tumbling noisily in and out of their ever-open front door. They never asked me in, so I would hang about the door waiting for Maureen to come out and play.

I thought they were the Family from One End Street, the Ruggleses from Eve Garnett’s children’s book. In that classic 1930s story, Mr Ruggles was a dustman, Mrs Ruggles was a washerwoman, and Lily Rose their eldest looked out for their other six children, including the twins and baby William. It was a groundbreaking book at the time, seen as radical, these stories of everyday working class life, though it was read, I imagine, mostly by children like me envying the daily scrapes and the scraping up of pennies for an annual family treat.

Polly, aged seven

Maureen (whose name wasn’t Ruggles) and I played fairies in the corn fields, crept about scaring each other in St Peter’s churchyard next door, water-divined in the ditches with hazel switches, drew hopscotch squares on the road and threw five-stone pebbles on and off our knuckles. One day we had a cart, an old orange box set on pram wheels. Was it her brother’s? Where did we find it? I don’t think we made it ourselves. We took it in turns pulling along the rope harness and riding in the box, up and down the flat road outside her house, shouting Giddy-up and Goa-on, waving a stick as a mock whip. It was my turn, I was in the box and Maureen was yoked in as my horse, she heaving me along making neighing and whinnying noises while I whooped and thrashed the air with my stick. Suddenly, there came a loud yell, a bark of command. ‘Maureen! Get right back in the house, now! Right now!’ Her mother was standing in the doorway with the baby in her arms. ‘You, who do you think you are, your ladyship, getting my girl to pull you around! What makes you think she should pull you, eh? Off you go home and don’t you ever, never come back round here again!’ Maureen dropped the rope and scuttled back home. I thought she’d explain we were taking turns, but she was scared of her mother. I jumped out of the cart and ran all the way back to my father’s house in tears of indignation. Not fair, unfair! But something else in me knew very well that there was another unfairness that wasn’t about taking turns, that couldn’t be explained away. Somewhere deep inside, I knew it meant Maureen would never have the turns I had. And Maureen’s family knew it well enough. They were plainly nothing like the Ruggleses in the book, who were always cheerful, not overly bothered by their lowly place and not resentful of the better off. Nor were Maureen’s family like another book I loved, about Ameliaranne Stiggins and her five siblings. Of similar disposition to the Ruggleses, the Stigginses were ever grateful to the squire and his tea party for poor children.

Jackie

I was always looking for friends in the lonely weekends and holidays at Cob Cottage, where my sister and I, children of divorce, had our time parcelled out precisely between South Kensington and Suffolk, staying with my father and stepmother. Josephine was rarely companionable: when we were sent out to ‘play’ she always asked me which way I was going, and then walked off in the other direction. When she grew too tall for it, her knees knocking the handlebars, I was passed on her old purple Raleigh bike and I pedalled it all the way to Kersey, the chocolate box village with a steep hill that races down to a ford running across the road at its foot, a zoom and a splash well worth the bike ride.

Beside the ford was the Bell Inn and one day I met Jackie riding her bike in and out of the water too, slow pedalling around the minnows and the pebbles. I went back to play with her often and I looked up at her village school just up the hill with longing as she talked about their playground games there. But most of all I envied Jackie her home above the pub, where her father was landlord. Up the winding back stairs, into a small snug, she had things I wasn’t allowed – a big tin of Quality Street ever open to dip into, bottles of Vimto whenever we wanted and a knee-high pile of comics – Dandy, Beano, Girls’ Crystal, Bunty, School Friend, all the best.

‘Ask her here,’ my father and stepmother kept saying, ‘ask her to lunch,’ so I did, with fearful trepidation. But when I pedalled back to Kersey, she was surrounded by village friends. ‘Here she comes, Miss La-di-da!’ one shouted out at me. ‘Oh I say, I’m just going to check my Rolls-Royce is in the garage!’ mocked another. ‘Oy, posh-pants! Bet you think you’re better than us!’ a boy called out, with more of the same. I thought Jackie would stand up for me, but I was the outsider. And every time I opened my mouth, the noise that jumped out like a box of frogs only drew more mimicry.

When they had gone, I asked Jackie if she’d come to my house for lunch, and she said yes, but with a sort of shrugged diffidence. I was gripped by anxiety: she wouldn’t like our food, it wouldn’t be as good as hers. Nothing I had was as much fun, no sweets, no comics. Did she play board games? She’d be bored. I played country games, camping in the old hay wagon beside the allotment, but she wouldn’t reckon much to that. I lit fires and cooked up soups made of nettles and herbs, playing witches, but she’d think that was disgusting.

Here’s the damned subtlety of class: she had more stuff that children want, but I was posh. My father’s cottage didn’t even have electricity until a few years later, only paraffin lamps with mantels, pumped up and lit at dusk. Her clothes were smart, I only wore baggy jeans too short up the calf and a home-knitted jersey. My plaits were old-fashioned, she had a cool bob like Bunty. What of our cooking would she eat? I begged for sausages and mash, the only thing that seemed safe. And please no cabbage. The next day I stood by the window and waited and waited and waited, but she didn’t come. I cried. My father was perplexed. When I rode back to Kersey the following day I waited and waited by the ford until eventually when I saw her she was with the same group of friends, and she just said, ‘You’re not my type,’ and rode off with them. And that was that. I knew it was true, but not fair. Jackie Bull of the Bell and Maureen of Lindsey Tye, where are you now?

Joe the Milkman

If I couldn’t find friends in the half of my life and the long holidays I spent at Cob Cottage, I did find work, or an early fascination with it. Three mornings a week at exactly 5.45 a.m. Joe came by Cob Cottage on his milk truck and I, aged about nine, would be waiting for him at the gate, alarm set not to miss him. He was a whistler, but not much of a talker. ‘Jump up,’ he’d say and off I’d go with him for the morning, counting out the right bottles for each house in one village after another. I read out the notes tucked into the empties, sometimes orders for cream in glass bottles too, eggs, white sliced loaves, and money in a twist of paper to be noted down in his cash book, tucked into his aged leather pouch slung round his overalls on a strap.

This was the job I wanted when I grew up, real work, useful, practical, pounding up and down pathways, clinking bottles, wary of barking dogs. ‘You’re a useful lass,’ he’d say when the round was done and I glowed with more pride than if a teacher had given me a star and a red tick –...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | Integrated B&W images throughout |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Makrosoziologie | |

| Schlagworte | anti-fascist • Arnold Toynbee • Bertrand Russell • Boris Johnson • Castle Howard • champagne socialism • Class • class divide • Class in Britain • communism • hons and rebels • Jessica Mitford • Labour Party • Lady Glenconner • lady in waiting • Left-Wing • Nickel and Dimed • Oxford • Oxford University • philip toynbee • Socialism • Toynbee Hall |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-836-3 / 1838958363 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-836-7 / 9781838958367 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich