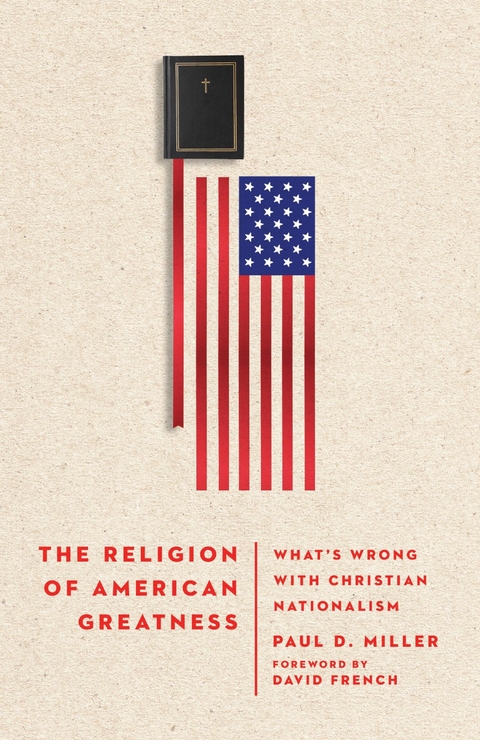

Religion of American Greatness (eBook)

304 Seiten

InterVarsity Press (Verlag)

978-1-5140-0027-4 (ISBN)

Paul D. Miller (PhD, Georgetown University) is Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service and co-chair of the Global Politics and Security concentration. He spent a decade in public service as director for Afghanistan and Pakistan on the National Security Council staff, an intelligence analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency, and a military intelligence officer in the US Army. Miller's writing has appeared in Foreign Affairs, The Dispatch, The Washington Post, Providence Magazine, Mere Orthodoxy, The Gospel Coalition, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. He is the author of Just War and Ordered Liberty.

ECPA Top Shelf Award WinnerLong before it featured dramatically in the 2016 presidential election, Christian nationalism had sunk deep roots in the United States. From America's beginning, Christians have often merged their religious faith with national identity. But what is Christian nationalism? How is it different from patriotism? Is it an honest quirk, or something more threatening?Paul D. Miller, a Christian scholar, political theorist, veteran, and former White House staffer, provides a detailed portrait of and case against Christian nationalism. Building on his practical expertise not only in the archives and classroom but also in public service, Miller unravels this ideology's historical importance, its key tenets, and its political, cultural, and spiritual implications. Miller shows what's at stake if we misunderstand the relationship between Christianity and the American nation. Christian nationalism the religion of American greatness is an illiberal political theory, at odds with the genius of the American experiment, and could prove devastating to both church and state. Christians must relearn how to love our country without idolizing it and seek a healthier Christian political witness that respects our constitutional ideals and a biblical vision of justice.

Paul D. Miller (PhD, Georgetown University) is Professor of the Practice of International Affairs at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service and co-chair of the Global Politics and Security concentration. He spent a decade in public service as director for Afghanistan and Pakistan on the National Security Council staff, an intelligence analyst for the Central Intelligence Agency, and a military intelligence officer in the US Army. Miller's writing has appeared in Foreign Affairs, The Dispatch, The Washington Post, Providence Magazine, Mere Orthodoxy, The Gospel Coalition, Foreign Policy, and elsewhere. He is the author of Just War and Ordered Liberty.

WHY NATIONALISM? WHY NOW?

The resurgence of nationalism in the twenty-first century is a response to decades of weakening national identities driven by globalization and tribalization. After the end of the Cold War, capitalism and democracy appeared to be the “final form of human government,” and their triumph was hailed as the “end of history,” as Francis Fukuyama argued.1 Dozens of countries in Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, Africa, and Latin America transitioned to some form of democratic and capitalist systems and joined the emerging global economic and trading regime. But that regime came with a price: every country that participated, including the United States, had to open itself up to foreign investment, multinational corporations, and the creative destruction—which sometimes felt more destructive than creative—of hypercompetitive global capitalism. These forces, seemingly unresponsive and unaccountable to any national governing authority, were unimpressed with local difference and cultural particularity. Globalization led to deindustrialization, the loss of manufacturing jobs, and the homogenizing and depressing sameness of “McWorld,” as Benjamin Barber termed the global monoculture that was everywhere and nowhere.2 Many consumers enjoyed lower prices and cheap goods, and hated everything else about McWorld, but also felt powerless to stop or reverse its impact on their communities because it was unresponsive even to their national governments. McWorld felt condescending, arrogant, bland, imperial, and soulless.

At the same time, national identity has been weakened from below by fragmentation, balkanization, and tribalization. The Cold War had forced virtually every nation in the world to pick a side, capitalist or communist, and participate in a decades-long ideological struggle that overrode differences in culture, identity, religion, and region. When the Cold War ended, subnational identities reemerged with a vengeance. Civil war erupted in Yugoslavia and Afghanistan along ethnic and religious lines; ethnic violence and civil unrest wracked Armenia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan; genocide tore Rwanda apart and sent chaos tumbling into the Democratic Republic of the Congo next door, which spent most of the 1990s as the center of a major international war that left some ten million dead. In the developed world, subnational identities led to calls for autonomy, decentralization, and even secession, from the Québécois of Canada, Catalonians of Spain, and Scots of Britain, to the Flemish and Walloons of Belgium and the “velvet divorce” of Czechs from Slovaks. Though it dates at least to the end of the Cold War, the rise of reactionary, atavistic subnational identities has accelerated in recent years in response to the apparent soullessness of global capitalism, the sclerosis of liberal democracy, and the 2008 financial crisis and recession. The Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing economic downturn seem to have accelerated these trends.

In the United States, American national identity has always been conceived somewhat differently than in the rest of the world, and thus its experience of globalization and fragmentation has also been different. In globalization, it could see its own image reflected dimly in the triumph of its ideals abroad, and the American foreign policy establishment largely supported the strengthening of international ties, the creation of new international organizations (such as the World Trade Organization in 1995), and the expansion of cooperative security (through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization). But America was not immune from the same forces of cultural homogenization and deindustrialization that afflicted the rest of the world, and so Americans too eventually grew disillusioned with globalization. Tribalization found traction because of America’s vastly greater pluralism, compared to Europe, and because academia gave it an official ideology in the form of multiculturalism and identity politics. Scholars and activists, mostly on the left, have increasingly argued that American identity is deeply, even irredeemably flawed because of its historical complicity with racism, slavery, and other historical crimes. Historically oppressed peoples, they argue, should cultivate an attachment to their own particular identities, advocate for the advancement of their group, and withhold loyalty to any shared sense of American identity, while scholars engage in ceaseless, unstinting critique of the American experiment.

This is the problem that nationalists want to solve. A substantial number of people—at least a plurality of Americans and a broadly similar number of Europeans—believe that their national identity is good, endangered, and worth fighting for. They feel that globalization has gone too far and tribalization is too dangerous. Nationalism is one of the main political and cultural responses to these trends, an effort to salvage and revive a meaningful sense of national identity between the global and the tribal. It is both an ideology for political action and a cultural movement seeking to revive lost (or imagined) senses of national identity and national solidarity. I sympathize with much of their critique of globalization and tribalization, and I agree that national identity can be good and healthy (see chap. 10). However, nationalists’ solutions are deeply flawed: nationalism turns out to be just another form of tribalization and just as corrosive of a healthy national identity as many of the trends they rightly decry.

LOVE OF COUNTRY

What is nationalism, and how does it differ from patriotism? Why would President Trump say that “we’re not supposed to use that word”? Is nationalism a good way of thinking about politics? Is there an alternative? In this book I argue that nationalism is generally a bad idea. Before I can make the argument, I need to define my terms—and here already we run into a problem. As I’ve developed this argument over the past several years, I’ve heard a common complaint: this is just a game of words that depends entirely on how we define nationalism. I’ve stacked the deck by defining nationalism in wholly negative terms, critics say, so that by the time I’m done simply defining the word, my argument that nationalism is bad is a foregone conclusion. In particular, many nationalists claim that nationalism simply means the love of country. I disagree: as I show later, the word carries a lot more meaning than that—and even nationalists who claim to mean nothing more than “love of country” often actually mean more because of how they define the country. But first I want to address the love of country, simply considered on its own terms, which I call patriotism. I agree that the love of country is usually good, but we still need to be on guard against some common temptations to ensure our love is rightly ordered.

Loyalty and affection for our home and our tribe is instinctive, universal, and essential for human life. C. S. Lewis praised the “love of home, of the place we grew up in . . . of all places fairly near these and fairly like them; love of old acquaintances, of familiar sights, sounds, and smells,” as well as “a love for the way of life,” for “the local dialect,” and more.3 Edmund Burke rightly taught that we ought to cultivate affection for our inner circles of associations as practice for the next-most outward circle: “To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections.”4 More recently, Nigel Biggar, an Anglican theologian, ethicist, priest, and scholar at Oxford University, argued that “it is justifiable to feel affection, loyalty, and gratitude toward a nation whose customs and institutions have inducted us into created forms of human flourishing.”5 We have all experienced that combination of pride, fellow feeling, and grandeur that comes from being a part of something larger than ourselves, something important, some part of history. We have a natural bent for this kind of team spirit, group loyalty, or tribalism: a prerational, atavistic loyalty—emotional and instinctual rather than cerebral and philosophical—to the people and places that feel familiar and in which we see ourselves reflected.

This kind of love for our country goes hand-in-hand with what is sometimes called a “civil religion,” a collection of traditions for collectively celebrating our patriotic attachment.6 Virtually all of us participate in some aspects of America’s civil religion—the collection of symbols, beliefs, and civic liturgies that tie Americans together and create a sense of shared experience, including the flag, the Pledge of Allegiance, the anthem, and the feast days (Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Thanksgiving), Juneteenth, the musical Hamilton, days of prayer, parades, national museums, historical sites and battlefields, national cemeteries, statues of national heroes, the commemoration of achievements or shared experiences, honoring the military and its achievements, speeches about national purpose, and celebrating folkways like clothing, music, food, and dance. These are the modern form of tribalism, adapted to the large, mass politics of contemporary states.7

Is tribalism good or bad? This is a complicated issue because, whether it is good or bad, it is inevitable. We cannot simply get rid of it; humans will always find a tribe to be part of and to root for. Human beings are not best understood as individuals found in a state of nature. Rather, we are...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.7.2022 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | David French |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Spezielle Soziologien | |

| Schlagworte | american nationalism • American religious history • Conservative • Constitution • Democracy • DEMOCRAT • Donald Trump • Identity politics • Liberal • Make America Great Again • Patriot • Political Ideology • Political Science • Republican • United States of America • us history |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5140-0027-X / 151400027X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5140-0027-4 / 9781514000274 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich