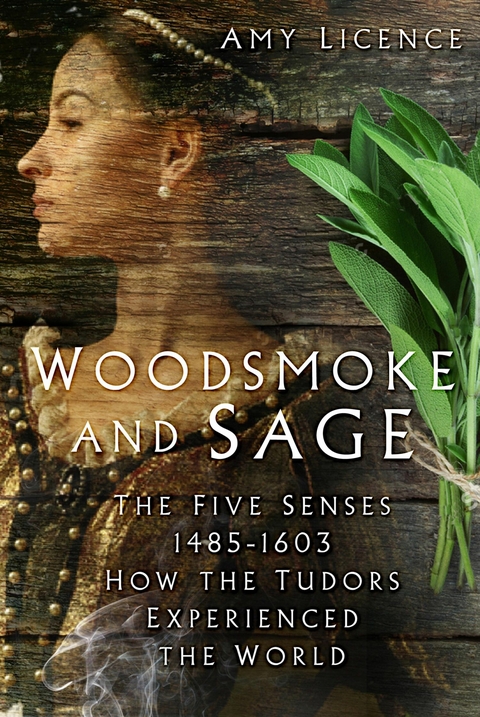

Woodsmoke and Sage (eBook)

384 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-9780-5 (ISBN)

Amy Licence is a bestselling historian of women's lives in the medieval and early modern period, from Queens to commoners. She is the author of Red Roses and The Lost Kings (both THP).

PEN AND BRUSH

THE AMBASSADORS

In 1533, the German artist Hans Holbein completed a new work, painted in oil and tempera, upon oak boards cut from English woods. In rich tones of green and red, black and gold, he portrayed two young men, both foreigners in London like himself. They were the 29-year-old Jean de Dinteville, ambassador of Francis I of France, and the 25-year-old Georges de Selve, soon to be Bishop of Lavaur, whose ages are inscribed upon the ambassador’s dagger and on the page end of the bishop’s book respectively. They gaze directly back at the viewer with a mixture of pride and patience, meeting our eyes at a time when the sitters of most court portraits, even members of the royal family, including the king and queen, are portrayed in demure semi-profile. These men are bold. They are cultured and fashionable. They have money. They want you to know it.

Dinteville, who commissioned the work, stands on the left, dressed in the most elegant outfit for an ambassador: a black velvet doublet and pink silk shirt, slashed with white at the chest and wrists. Over it, he wears a heavy coat with puffed sleeves, lined with lynx fur, and the fashionable round-toed shoes of the Tudor court. De Selve’s colouring is more modest, his long brown gown with fur lining covering a plain black garment and white collar beneath, more suitable to his religious calling. He wields his gloves in his right hand and wears the trademark soft, black Canterbury cap of Catholicism, with its square corners.

Together, these two young men have come to be known to history as The Ambassadors. For years, they hung in Dinteville’s chateau in the village of Polisy, about 125 miles south of Paris, but now they are seen daily by thousands of visitors to London’s National Gallery. And they offer the modern viewer a glimpse into the crucial theme of sight and perception in the Tudor world.

Dinteville and de Selve are the main dishes in a Tudor visual feast. As part of a carefully composed still life, they lean upon a two-shelved unit, over which is draped an expensive oriental tapestry, a status symbol more commonly found over tables than underfoot. Although the centres of the European tapestry market were in the Netherlands and Arras, this piece appears to have come from a more exotic Turkish location. Items on the top shelf represent man’s study of the heavens: a celestial globe painted with the constellations; a sundial and other astrological instruments used to measure time and space; a quadrant, a shepherd’s dial and a torquetum, which was a sort of prototype analogue computer.

The shelf below displays a collection of earthly pleasures: a terrestrial globe, a pair of flutes, lute, compass, a book of arithmetic and a Lutheran psalm book, representing the new religious influences that the Catholic de Selve continued to resist. Further subtle references are made to the Reformation through the prominence of the Latin word dividirt, or ‘let division be made’, and the broken lute string of ecclesiastical disharmony.

The top left-hand corner contains a crucifix, partially concealed behind the heavy green backdrop, and scholarly analysis of the various instruments indicates a date of 11 April, or Good Friday, 1533.1 The ensemble stands upon a polished marble floor, taken from the Cosmati design in the sanctuary at Westminster Abbey, of inlaid coloured stones in geometric shapes. One of the floor’s original inscriptions, created in the year 1268, stated that the ‘spherical globe here shows the archetypal macrocosm’ with the four elements of the world represented in the design, which were believed to also govern the human body, or world, in microcosm. The ambassadors want us to know they are standing at the cutting edge of technology, in a rapidly changing world.

But the picture’s ‘trick’ is hidden. To the casual observer, even one standing in awe before the work, the most famous detail of The Ambassadors might pass completely unnoticed. Nestled in the centre at the bottom, between the two men’s feet, sits an anamorphic skull, distorted in paint so that it leaps into perspective only when the viewer looks at the canvas from a certain angle. Visitors to the National Gallery are directed to a vantage spot marked on the floor, where the image suddenly jumps into life. This morbid shock was quite deliberate, and continues to surprise twenty-first-century observers, but it was somewhat unusual for Holbein, who is likely to have been acting on the instructions of the sitters.

Dinteville chose the term ‘memento mori’ as his personal motto, a reminder of human mortality, which was a frequent motif in medieval and Tudor culture. This theme is also represented in the brooch he wears upon his cap, featuring a grey skull on a gold surround. The skull on the floor symbolises the inevitability of death and the spiritual life, in contrast with the material and temporal luxuries on display. Its deceptive perspective reminds us that death is always present, waiting to claim us, even when we cannot see it, but the element of surprise is paradoxically playful and macabre.

More sinister, perhaps, is the implied limitation of human perception, a sobering and humbling observation despite all the science and learning displayed in the picture. Not even the sophisticated instruments of measurement, of which the ambassadors appear so proud, can predict the approach of death. Seen and unseen, the memento mori is, both of the picture and external to it, a trompe l’oeil whose very skill exposes the complex message of mortal strength and weakness. And yet, perhaps, it is the act of painting, art itself, or artifice, which has the final word. For while the two young men are dead and buried, claimed by the Grim Reaper almost five centuries ago, they still stand staring out at us today – colourful, larger than life, in the pink of health.

The Ambassadors also contains a number of contrasts: macrocosm and microcosm, heaven and earth, world and man. And thus, it helps establish a sense of scale in the Tudor aesthetic – the individual as a cog in the wheel of God’s plan. By surrounding Dinteville and de Selve with the accoutrements of Humanist and Reformation learning, the artist identifies them, by association, as being contextual with global exploration, science and the arts, social hierarchies and the unfolding crisis in the English Church. In commissioning the details of this work, the ambassadors have selected favoured objects as a cultural shorthand, a cherry-picked collage of their specific, Humanist world. Posing amid these symbols, they offer their carefully crafted identities, in microcosm, to the transformative process of paint. Their chosen moment is given a permanence by the artist’s brush, which had the ability to outlive old age, changing fortunes and death, so long as the work survived. The act of painting, and the physical existence of the work itself, gives them an empirical position within an aspirational social framework.

Holbein’s masterpiece was an intellectual exercise as well as an aesthetic one. The image is crammed full of visual clues for his cultured contemporaries to decode, a complex and detailed message that requires sufficient learning to unpack. It was designed to appeal to an elite, but its majestic impact would not have been lost on any strata of society, should they have had access to view it.

A parallel experience for those lower down the social scale, the majority of whom were illiterate, could have been the walls and windows of colourful pre-Reformation ecclesiastical art. Depicting saints and sinners, the performance of miracles and damnation in hell, these were plastered above their heads on an immense scale whenever they went to pray, reinforced by the deliberate contrast made of light and darkness, of flickering candles in the gloom.

The Tudors were a highly visual culture and the ‘look’ of things mattered to them. This was true right through the social spectrum, from the poor woman’s pleasure in receiving the bequest of a new gown in a friend’s will, to Elizabeth I’s cloak embroidered all over with eyes and ears, implying that she saw and heard everything. That large percentage of society who could not read were far from being visually illiterate.

The Tudor elite used heraldic devices, badges and liveries as indicative of their lands and lineage: animals and flowers, symbols that were instantly recognisable. However, a rise in mercantilism and an increased social mobility by meritocracy allowed the middle classes to adopt their own series of visual codes. Everything that could be seen, from the rings upon a finger to the shape of a shoe, were coded references to social hierarchy.

In such an aspirational culture, clothing increasingly replaced birth as the first indicator of personal identity, allowing for acts of sartorial stealth and deception like never before. The Tudor man or woman would attempt to wear and display the accoutrements of a higher social stratum, as a means to achieving it. Size and quantity mattered. Location mattered. Subject to strict hierarchies, you would judge, and be judged, by the material self you projected.

The Ambassadors offers a useful entry point to the complicated material culture of the sixteenth-century world. The deliberate way in which it was planned, composed and executed reveals the centrality of personal status to the Tudors. Holbein demonstrates this through his presentation of the complex identities of Dinteville and de Selve, in terms of clothing and appearance, posture and positioning, and the careful, deliberate...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.8.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | Edward VI • Elizabeth I • Henry VIII • Mary I • material culture • Senses • The Five Senses 1485-1603: How the Tudors Experienced the World • tudor culture • tudor drink • tudor food • Tudors • tudors, henry viii, edward vi, mary i, elizabeth i, material culture, tudor clothes, tudor food, tudor fashion, tudor perfume |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-9780-X / 075099780X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-9780-5 / 9780750997805 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 29,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich