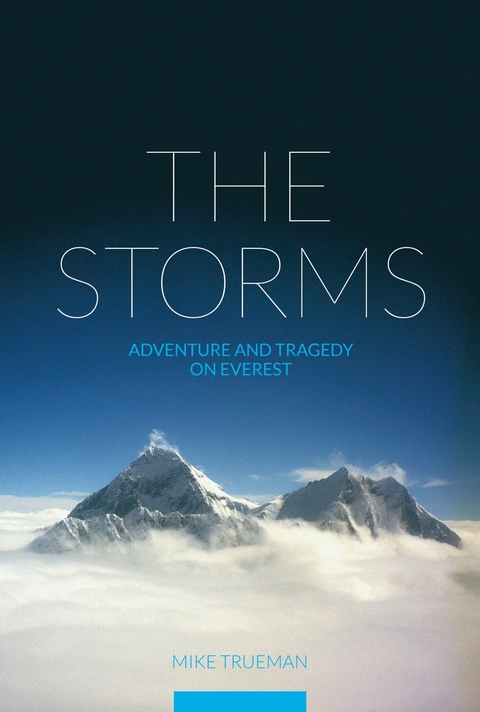

The Storms (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-898573-95-1 (ISBN)

– Chapter 2 –

Boy Soldier

I joined the British Army as a ‘boy soldier’ at the age of sixteen in 1968. Some thirty-nine years later I was head of a United Nations team tasked to remove ‘soldiers’ of a similar age from the ranks of the Maoist army at the end of the civil war in Nepal. While my friends at the grammar school I had just left were enjoying their final two years of education, I was part of a hard regime which was ‘beasted’ from before dawn until well after normal people would have gone to sleep.

Most of the instructors who guided us through those embryonic days of our military service were experienced soldiers, well-skilled in passing on their knowledge, but there were the exceptions. The last post-Second World War conscripts had left the British Army in 1963 and in 1968 the odd instructor still relied on harsh bullying from this era to guide their charges.

I have few fond memories of those exacting days, except for the times, every three months, when we were given the opportunity to take part in adventurous activities. I canoed, climbed and went on a parachute course, but it was my experience at the Army Outward Bound School that was to have the most long-term effect. In those days we were graded on the course and I was fortunate enough to be given a rarely awarded ‘A’ grade, which was to have an impact on my career. It certainly helped to counteract the report I received at the end of my time as a boy soldier, which to some extent reflected my response to an ogre of an instructor. At some stage during most weeks of my last term, I appeared for a disciplinary interview in front of my company commander, on a trumped-up charge made by a particular bully of an instructor.

I knew a lot about the weapons of the British Infantry when I became an ‘adult’ soldier in 1970, but I knew very little about life outside of the army. I was naïve and rightfully failed a selection process to become an army officer, and this led to disillusionment with my chosen career. It wasn’t, however, a case of giving a month’s notice. Having ‘signed on’ for a number of years, the only way to get out of the system – and even this took many months – was to purchase a discharge and the army made sure that this was a very expensive option.

I transferred to an air despatch unit at Thorney Island on the south coast of England. This was the start of four very happy years, during which I changed from a disillusioned teenager into an ambitious adult. The unit was tasked with delivering supplies and equipment by parachute to forces around the world, and also with providing support during civilian emergencies, such as the distribution of food during the famine which hit Nepal in 1973 – a task I sadly missed.

In the early 1970s Britain’s army was focused on operations in Northern Ireland, a necessary security role, but somewhat separated from the type of soldiering I dreamed of being involved in when I joined the army. The enemy could have been anyone who you passed on the streets of Belfast, a city hardly different from any other part of the United Kingdom. The extreme verbal abuse – which would have offended a sailor in Nelson’s navy from the mouths of children not old enough to go to school – through to elderly people older than my grandparents, was a sad reflection of the depth of hatred which existed in post-war twentieth century Britain. It would be years before I would experience a similar level of hatred in the war in the former Yugoslavia.

One of the tasks of 55 Air Despatch Squadron was to support Britain’s Special Forces, and in the early 1970s the opportunity to be attached to an SAS squadron during the war in Oman’s southern province of Dhofar was as emotionally exciting at one end of the spectrum as soldiering in Northern Ireland was emotionally depressing at the other end. I first went to Dhofar in 1971 when our crew of four was attached to G Squadron of the SAS. Our arrival was delayed because the enemy was firing at the airfield at Salalah, but we got down eventually after the guns defending the airfield located and destroyed the enemy.

This was Britain’s secret war, unpublicised by the government of the day, fought against the tribes of the Dhofar province who had been encouraged to rebel by a Maoist group, the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf. It was so secret that when two SAS soldiers were shot and evacuated to Sharjah, where they died, we were tasked to load the coffins, ‘camouflaged’ by a surrounding crate and fly with them to Bahrain, where I last saw them as they were trundled, like any other piece of cargo, on a forklift from the aircraft to the hangar.

I returned to Dhofar in 1973 attached to B Squadron 22 SAS. By this stage of the campaign the SAS, and the local forces they led, had established bases across the mountains bordering the coast of southern Oman. This part of the world suffers from the ‘Khareef’, a seasonal monsoon which starts in June and lasts for some weeks. This weather system causes the mountains to be covered in cloud down to ground level for much of the time, which prevents daily supply flights to the small bases in the mountains. For a large part of the time I was located at a base called White City, which was usually reached by an easy thirty-minute flight in normal weather. During the Khareef it took two long days to get there, first on a flight over the mountains into the desert, then in a convoy led by vehicles designed to detonate mines, and protected by guns and overflying jet aircraft and, lastly, as part of a heavily armed foot patrol through thick fog with the potential for ambush at any time.

Our position was commanded by Fred Marifono, one of several Fijians in the SAS, and a giant of a man in both body and personality. A year before, two of these Fijians, ‘Laba’ Labalaba and ‘Tak’ Takavesi had displayed great courage at the Battle of Mirbat when a large enemy force attacked the coastal town. Nine SAS soldiers were largely responsible for holding off an enemy force numbering hundreds until being reinforced by G Squadron who had just arrived in Oman to take over from B Squadron. At the height of the battle Laba had single-handedly loaded and fired a vintage World War Two artillery piece. After Laba was wounded Tak volunteered to move hundreds of metres to the gun to support his friend. Together they continued to fire the gun at point blank range, until Laba eventually received a fatal wound. Propped up against sandbags and having been shot through the shoulder and stomach, Tak continued to fire his rifle at the enemy. For his part in the action Tak was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and Laba was mentioned in despatches – many of his comrades believe this should have been a very well-deserved Victoria Cross.

A year to the day after the battle I was based at Mirbat, where I was responsible for the airfield operations. Having been soundly defeated a year before, the enemy didn’t reappear, but as the anniversary dawned I was struck by an emotionally charged visualisation of the great feat of arms which had taken place a year before on that July day in 1972.

I had decided to make the army my career, which was a significant change from my period of disillusionment some four years before, and I applied again to become an officer. While waiting to attend the Commissions Board I was posted as an instructor to the Joint Services Mountain Training Centre, which was based on the windswept west coast of Wales. It was partly a result of my performance at my Outward Bound course in 1969, and of my participation the year before in the annual joint British/Italian mountaineering exercise in the Italian Alps, that I was able to secure this job. Every year a group of British army climbers would spend two weeks in the mountains of Wales or Scotland undergoing a tough selection process to decide who would then go on to spend three weeks climbing in the Alps with the Italian Alpini (mountain regiment).

As a keen climber this was a fabulous opportunity to spend weeks at the army’s expense doing what I did most weekends at my own expense – it was a no-brainer. I had previously taken part as a relative Alpine novice in 1972, but in 1974 I was back as a climbing group leader. The Alpini were superb instructors and we were given their best to work with. Two of our instructors, Virginio Epis and Claudio Benedetti, were particularly note-worthy having become, in 1973, the thirty-fourth and thirty-fifth climbers to reach the summit of Everest, and it was this experience to climb with such outstanding mountaineers that moved my interest in climbing up another gear. It was also my first experience of just how fragile life in the mountains could be. I had led a steep but straightforward ascent on hard snow when the second climber, who I was belaying from above, slipped just short of my stance. I watched with horror as he fell down the slope, very concerned that I wouldn’t be able to stop him falling and even more concerned about what would then happen to me because I wasn’t overly confident about my belay. I soon had my concerns answered as my belay gave way and I rocketed out into space and then tumbled downwards before coming to an abrupt stop some twenty-five metres down the slope, overlooking a series of deep crevasses. The number three on the rope, who had been belaying from below, was fortunately a very experienced Alpini climbing instructor, whose strength and skill certainly saved us from serious injury, or worse.

Interestingly, there was a link between the 1973 and 1996 Everest seasons. In 1973 the Italians had used a Hercules aircraft to fly a helicopter into Kathmandu which they subsequently used to supply their expedition up to Camp 2 in the Western Cwm. During a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.5.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-898573-95-6 / 1898573956 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-898573-95-1 / 9781898573951 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich