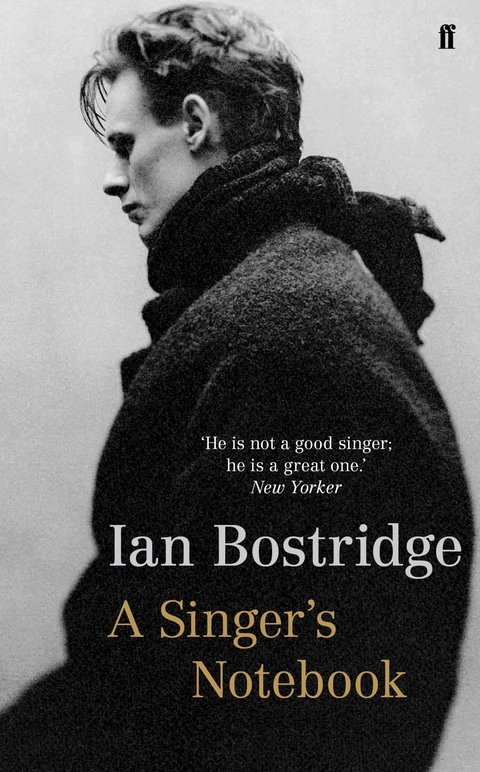

Singer's Notebook (eBook)

272 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-25467-5 (ISBN)

Ian Bostridge is universally recognised as one of the greatest Lieder interpreters of today. He has made numerous award-winning recordings of opera and song, and gives recitals regularly throughout Europe, North America and the Far East to outstanding critical acclaim. On stage, he was the original Caliban in Thomas Adès's The Tempest, and he played Gustav von Aschenbach in the landmark 2007 production of Death in Venice directed by Deborah Warner. In 1999 he gave the premiere of Hans Werner Henze's song cycle, Sechs Gesänge aus dem Arabischen, which was specially written for him, and which was subsequently recorded. He read Modern History at Oxford and received a D.Phil in 1990 on the significance of witchcraft in English public life from 1650 to 1750. His books include Witchcraft and its Transformations c.1650 to c.1750 (1997), A Singer's Notebook (2011) and Schubert's Winter Journey (2015). He is Humanitas Professor of Music at Oxford, and a regular contributor to the Guardian and the TLS. He is married to the writer and critic Lucasta Miller, and they live in London with their two children., Ian Bostridge is universally recognised as one of the greatest Lieder interpreters of today. He has made numerous award-winning recordings of opera and song, and gives recitals regularly throughout Europe, North America and the Far East to outstanding critical acclaim. His books include A Singer's Notebook (Faber, 2011) and the award winning Schubert's Winter Journey (Faber, 2016). He was Humanitas Professor of Music at Oxford 2014/15 and has been a regular contributor to newspapers and journals in the UK and US including the Financial Times and the New York Review of Books.

Ian Bostridge is one of the outstanding singers of our time, celebrated for the quality of his voice but also for the exceptional intelligence he brings to bear on the interpretation of the repertoire of the past and present alike. Yet his early career was that of a professional historian, and A Singer's Notebook takes a look at the multifaceted world of classical music through the eyes of someone whose career as a singer has followed a unique trajectory. Consisting of short essays and reviews written since 1997, some in diary form, it ranges widely over issues serious (music and transcendence) and not so serious (the singer's battles with phlegm), while inevitably discussing many of the composers with whom Bostridge has become identified, such as Benjamin Britten, Henze, Janacek, Weill, Wolf, and Schubert, composer of the Winterreise with which Bostridge has become so associated. Ultimately it returns to the theme of his earlier work on seventeenth century witchcraft - what place can there be for the ineffable in a world defined by an iron cage of rationality?Including a foreword by the eminent sociologist, Richard Sennett, A Singer's Notebook is an intriguing glimpse into the mind and motivation of one of Britain's best loved musicians.

Born in London, Ian Bostridge is universally recognised as one of the greatest Lieder interpreters of today. He has made numerous award-winning recordings of Lieder and gives recitals regularly throughout Europe, North America and the Far East to outstanding critical acclaim. He read Modern History at Oxford and received a D.Phil in 1990 on the significance of witchcraft in English public life from 1650 to 1750. His book Witchcraft and its Transformations 1650-1750 was published in 1997.

I started writing a column for the new monthly magazine Standpoint in 2008, really as a sort of discipline. Over the past fifteen or so years as a singer, I have tried on several occasions to write a diary, but have never managed for more than a week or so. When I recorded one on old-fashioned cassette tapes, often in the bath at the end of the day, during the whole five-week rehearsal period for Deborah Warner’s staging of Seamus Heaney’s new translation of Janáček’s The Diary of One Who Vanished, inspired mainly by the wittily recursive possibilities of writing a diary about The Diary, I didn’t get very far – not surprisingly. I had, I now realise (listening back to the tapes) very little to say. Or rather, I didn’t have the energy, in the midst of struggling with the production, to struggle to say what needed to be said. One of the most extraordinary things about great subjective writing – Proust, say, laying out, anatomising and characterising a train of thought – and also about great diary writing, is the capacity to be dogged, not to let go until every little strange and unexpected turn of thinking has been teased out. Much of what I have listened to of these tapes, ten years later, seems to veer away from what was actually interesting about the work, or to obsess with practical or factual trivia – times of meetings, names of participants, meals eaten, objective tasks undertaken. Performing work is fascinating and creatively engaging, both in the encounter with canonical musical and literary texts, and in the opportunities it offers for collaboration with imaginatively gifted people – writers, directors, musicians, actors – but I have never been able to capture this in the essentially subjective, stream-of-consciousness, informal form of the diary.

So these pieces for Standpoint are partly in lieu of a diary: another attempt, since I was given the wonderful freedom to write about whatever I happened to be doing or thinking about that month. Some of them reflect the old obsessions about the magic of music, some ruminate on the actual business of singing and performing. The other discipline – apart from that of the monthly deadline – was to try to find a different way of writing, to loosen up a little after all my years of academic work and the scrupulous avoidance, drummed into the academic brain, of the first-person singular. Really a discipline towards indiscipline, an attempt to find a more relaxed form of expression. Maybe gearing up to write a diary, who knows? Anyway, after a year of writing, I took a rather grandly named ‘sabbatical’ from Standpoint to prepare this collection of fugitive pieces. Where I’ve had some further thoughts on the subjects discussed, I’ve added them.

June 2008

Bach is the irreducible indispensable of classical music. You would be hard pressed to find a performer who would admit to disliking him; and composers don’t use him – as Benjamin Britten used Beethoven and Brahms and Strauss, for example – to define a contrary aesthetic agenda. He is, as much as a dead white male can be, universal; and also, in a sense, pure. Concert pianists who spend a lot of their time with the Romantic longing that dominates the piano repertoire, from late Mozart to Rachmaninov, have been known to cleanse themselves with an icy immersion in the Bach keyboard works first thing in the morning.

In Bach there seems something morally uplifting: he was a supremely gifted artist, never to be surpassed, who founded an unbroken tradition in musical art, yet who was unwittingly, as it were, leading a day-to-day existence of surpassing ordinariness and, yes, decency. An assiduous, if prickly, municipal servant in Leipzig, he was a devoted father, married twice, to women who bore him twenty children between them: one in the eye for the supposed artistic imperative to excess and irresponsibility of a Lord Byron or a Jimi Hendrix.

Bach means ‘stream’ in German – in his own era and area of Germany there were so many of the Bach family in music that it had also come to mean ‘musician’ – and Bach’s purity, like that of limpid water, makes for an easy contrast with the worldly, commercially minded, theatrical Handel, whose name is reminiscent of German words for shop and business.

There is something to this notion. There is more in Handel of an Italian sprezzatura, music for pleasure; while Bach speaks more to the German taste for the earnest and the metaphysical. Handel died rich; Bach comfortable. Handel was one of music’s great plagiarists, repeating himself and stealing from others with gay abandon, while Bach seems to have generated most of his musical material himself. On the other hand, George Frideric Handel was a deeply religious man; and Johann Sebastian Bach was certainly not an angelic musical aesthete. None the less, the latter has achieved a sort of pre-eminence in music, a saintly quality, which has made his reputation immune to the vagaries of fashion or style, ever since the rediscovery of his music by the Romantic composers more than a century and a half ago.

After a long break – six years or so – I have been spending a lot of time with Bach over the past weeks on two very contrasting projects: a St John and a St Matthew Passion. St John’s Gospel is, of the four, the most theologically minded and mystical. Nevertheless, Bach makes of it, in his St John Passion, a work more deeply personal and thrustingly dramatic than the monumental and later St Matthew Passion, a work that he consciously saw as part of his legacy.

In the St John Passion, singing, as I do, the part of the Evangelist, the storyteller, it is very easy and, I think, proper to become involved in the act of narration and in the emotions of the narrative (though some people, misunderstanding the whole thrust of eighteenth-century German piety, find it vulgar). Bach takes very seriously the notion that St John was a witness to these events, a friend and disciple of Jesus Christ and the comforter of his mother. While the St Matthew Passion’s narrative is just as dramatic, with as much tenderness, violence and passion, the greater number of reflective arias, sung as if by present-day Christians who meditate on and participate in the drama, both interrupt the narrative more and lend the whole work a more universal aspect.

One particular moment in the Matthew struck me, for the first time, as a manifestation of the mundanity (in the best sense) of Bach’s genius. The aria for alto and oboes da caccia with choir, ‘Sehet’, speaks of Christ stretching out his arms to gather in the oppressed sinners, the ‘verlassnen Küchlein’ or abandoned chicks. What makes that homely image of Christ as a sort of mother hen so tender and moving is the extraordinary sound that the oboes make together: a clucking, farmyard noise.

My St John Passion took place in London, with the brilliant choral director and conductor Stephen Layton, and a band of old instruments – dramatic, almost theatrical, but deeply felt. Mannerism is often used as a negative term in criticising classical singing or playing, but in fact mannerism and its inflections are at the heart of what we do. What we have regained by using old instruments is a whole series of eighteenth-century mannerisms that had been lost; ways of articulating and phrasing which modern instruments and styles of singing, with their emphasis on line, blend and consistency of palette, had almost obliterated.

Singing the Matthew with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the legendary Bernard Haitink should, I suppose, have been very different. It was, amazingly, Haitink’s first performance of a Bach Passion. In all his years at the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam – which has a long and distinguished Bach tradition – he was never asked to conduct a Bach Passion, to his regret.

A modern orchestra like the Boston brings something different to these pieces, of course. Despite the virtues of all that has been discovered and revived by the period-practice specialists, it would be a perverse, self-denying ordinance that banned modern orchestras from playing this music. These are wonderful musicians whose musicality has been formed in the shadow of Bach. He is a deep composer, literally – one whose works function on many different levels; there are aspects of the music that only modern instruments can illuminate. There is no right and wrong. And in this case we were under the benign supervision of a great conductor, one who knows when to intervene and when to stand back and let it happen. It was a great way to come back to the Matthew.

But if I ask myself why I have missed these pieces so much, why they were for ten years such an important part of my singing year, I have to say that, typical Anglican agnostic that I am, they satisfied my religious instincts. I don’t think that’s just woolliness on my part. Bach’s music represents something very special: an end and a beginning. He is a late exemplar of the Renaissance sensibility that saw music as an embodiment and expression of the Divine order; composers who wrote after him, even composers who were truly religious or who were profoundly influenced by him, wrote music that lacked the confident expressivity of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.9.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Klassik / Oper / Musical | |

| Geisteswissenschaften | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Schlagworte | Benjamin Britten • John Eliot Gardiner • Lieder • Music Business • Richard Sennett • Schubert • schubert's winter journey |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-25467-5 / 0571254675 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-25467-5 / 9780571254675 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich