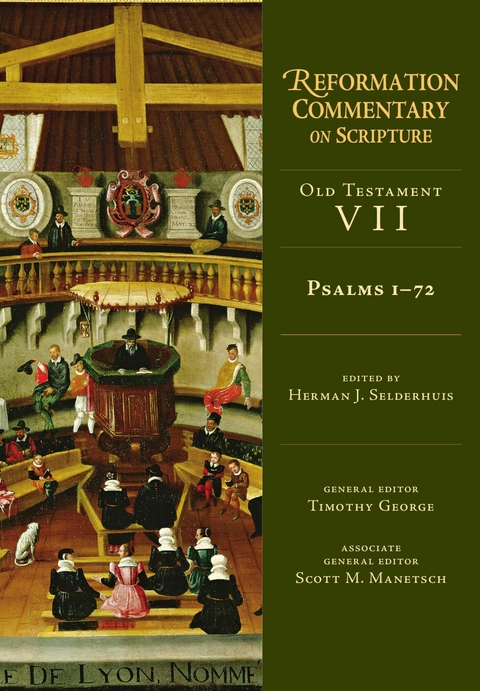

Psalms 1-72 (eBook)

566 Seiten

IVP Academic (Verlag)

978-0-8308-9818-3 (ISBN)

Herman J. Selderhuis is professor of church history and church polity at the Theological University Apeldoorn (Netherlands) and director of Refo500, the international platform for knowledge, expertise and ideas related to the sixteenth-century Reformation. He is a leading Reformation historian and author of several books, including John Calvin: A Pilgrim's Life and Calvin's Theology of the Psalms. He also serves as the academic curator of the John a Lasco Library (Emden, Germany) and as president of the International Calvin Congress.

Herman J. Selderhuis is professor of church history and church polity at the Theological University Apeldoorn (Netherlands) and director of Refo500, the international platform for knowledge, expertise and ideas related to the sixteenth-century Reformation. He is a leading Reformation historian and author of several books, including John Calvin: A Pilgrim's Life and Calvin's Theology of the Psalms. He also serves as the academic curator of the John a Lasco Library (Emden, Germany) and as president of the International Calvin Congress.

Introduction to the Psalms

Puzzled as to how he should approach and understand the Psalms, Marcellinus requested the aid of his friend Athanasius (c. 295–373). The great bishop of Alexandria willingly obliged him with a lengthy letter, recounting the advice he himself had received:

My child, all the books of Scripture, both old and new, are inspired by God and useful for instruction, as it is written. But to those who really study it, the Psalter yields especial treasure. Each book of the Bible has, of course, its own particular message. . . . Each of these books, you see, is like a garden which grows one particular kind of fruit; by contrast, the Psalter is a garden which, besides its particular fruit, grows also those of all the rest.1

Here in one holy book, Athanasius asserts, is the entire form and content of God’s revelation—creation, exodus, exile and redemption—fixed as praise, inviting our participation. “In the other books of Scripture we read or hear the words of the saints as belonging only to those who spoke them, not at all as though they are our own,” Athanasius continues. “With this book, however, . . . it is as if it is our own words that we read; anyone who hears them is pierced to the heart, as though these words voiced for him his deepest thoughts.”2 The Psalms are a mirror that reveals who we really are, instructing us to conform ourselves through the Spirit to the gift and example of Jesus Christ.3 Only with the guidance of the Holy Spirit—the true Author of these songs—is anyone able to read the Psalms intelligently.4 Athanasius’s letter has influenced more than Marcellinus. Many since, including Martin Luther, John Calvin and other commentators featured in this volume, have included choice phrases from Athanasius’s letter in their own works on the Psalms.5

For the fathers, the medievals and the reformers, the Words of Christ cannot be interpreted apart from the Spirit of Christ. Thus, praying the Psalms should not only align believers’ reason and affections but also conform their will to God’s.6 This is no perfunctory prayer. In a fit of conscience, Augustine worried that he did not pray the Psalms but instead was seduced by their sweet melodies. He longed to be “moved not by the singing but by the things that are sung.”7 Anything else is to sin grievously. Luther lamented, somewhat hyperbolically, that the Psalms were no longer understood on account of their second-class rank behind legends and histories of saints.8 Divine things had been exchanged for human things. In the preface to his influential Psalter, Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples accused himself and his peers of only paying “lip service” to the Psalms and theology.9 Ignoring the psalmist’s word—“Blessed are those who study your testimonies” (Ps 119:2)—they traded heavenly blessings for worldly blessings, pursuing the “literal sense,” which left them “utterly sad and downcast.”10

Christ and the Psalms: What Is the Literal Sense?

But aren’t the reformers famous for their insistence on the “literal sense”? Weren’t they responsible for freeing biblical interpretation from the chains and restraints of fables and allegories? It depends. What is the literal sense, and what allegories did the reformers disapprove of? Some readers may be surprised to find the reformers saying that certain psalms are literally about Jesus Christ. Today by the “literal meaning of Scripture” we mean its meaning according to the constraints of grammar, history and literary method.11 It is not uncommon to see contemporaries lambaste our forebears’ interpretations as fantasy. And yet specialists trace the revival of the literal sense to Nicholas of Lyra—in some cases even to Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274).12 Between the early modern period and today there has been a shift in our understanding of the literal sense.13

After an interview with monks depressed by their literal reading of Scripture, Lefèvre himself wondered, what do they mean by literal? “Then I began to consider seriously that perhaps this had not been the true literal sense but rather, as quacks like to do with herbs, one thing is substituted for the other, a pseudo sense for the true literal sense.”14 On reflection Lefèvre realized that these monks had been reading Scripture as if there were only a human author. They approached the Psalms considering only David and his context, errantly viewing him not “as a prophet but rather as a chronicler.”15 However, the testimony of the apostles, Evangelists and prophets demonstrates, for Lefèvre, that readers must lift up their hearts and contemplate the intention of a higher Author:

[The apostles, Evangelists and prophets] opened the door of understanding of the letter of Sacred Scripture, and I seemed to see another sense: the intention of the prophet and of the Holy Spirit speaking in him. This I call “literal” sense but a literal sense which coincides with the Spirit. No other letter has the Spirit conveyed to the prophets or to those who have open eyes.16

For Lefèvre, then, the letter that kills is the letter severed from its true Author, the Holy Spirit. Only by Christ’s aid—of one essence with his Spirit—will a reader be able to expound the literal sense of Scripture.17 “For [Lefèvre] the spiritual, that is, the literal sense is not available through simple grammatical exegesis,” Heiko Oberman summarizes. “The unbeliever cannot discover the real meaning because he approaches the text without the most necessary exegetical tool of all, that selfsame Spirit which created Scripture.”18

So then, Lefèvre intimates a twofold distinction within the literal sense: the simple and the spiritual, or what Richard Muller calls the constructed or compounded.19 The simple literal sense consists of the immediate grammatical, historical and literary meaning of the very words of Scripture; the spiritual literal sense is the meaning of the very words of Scripture in light of the full form and content of Scripture. The simple and the spiritual literal senses are distinguishable but inseparable. Nevertheless there is a hierarchy: the simple serves the spiritual. Other reformers wholeheartedly affirmed this approach. Luther was particularly insistent that Scripture’s substance, Christ, is the interpretive key for all its words.20

The vast majority of the reformers, not just Luther, affirmed that the concern for textual analysis must be wedded with the rule of faith, which Craig Farmer has tersely defined as “the trinitarian, christological and evangelical scope of Scripture’s content and meaning that arises from it and in turn makes sense of the whole and the parts.”21 All biblical interpretation must be ruled. Luther states this with characteristic flourish:

If I were offered free choice either to have St. Augustine’s and the dear fathers’, that is, the apostles’, understanding of Scripture together with the handicap that St. Augustine occasionally lacks the correct Hebrew letters and words—as the Jews sneeringly accuse him—or to have the Jews’ correct letters and words (which they, in fact, do not have everywhere) but minus St. Augustine’s and the fathers’ understanding, that is, with the Jews’ interpretation, it can be easily imagined which of the two I would chose.22

Luther would rather have a faulty but ruled translation than the original text divorced from the church’s faith. Even the more restrained Calvin affirms the essential importance of ruled interpretation. Paul, he explains, exhorted “those who prophesied in the church . . . to conform their prophecies to the rule of faith, lest in anything they should deviate from the right line.”23

The reformers’ understanding of the literal sense and the rule of faith helps us understand which allegories they protested against so harshly: those that were not conformed to the rule of faith. Luther is explicit:

When we condemn allegories we are speaking of those that are fabricated by one’s own intellect and ingenuity, without the authority of Scripture. Other allegories which are made to agree with the analogy of faith not only enrich doctrine but also console consciences.24

In his Institutes Calvin affirms this prescription of Luther: “Allegories ought not to go beyond the limits set by the rule of Scripture, let alone suffice as the foundation for any doctrines.”25 Here we see two giants of the Reformation affirming allegories that present Christ while casting aside all others (e.g., those that affirm papal primacy or purgatory).

Unsurprisingly, the reformers’ uses of ruled interpretation in the Psalms are on a spectrum, with Luther as the most ardent, Calvin as the most restrained and Martin Bucer in between.26 First, Luther and his disciples employ an immediate ruled interpretation.27 While at times they consider the specific historical data concerning David, generally they quickly venture into Christological details, often reading the Psalms in the person and voice of Christ:

Every prophecy and every prophet must be understood as referring to Christ the Lord, except where it is clear from plain words that someone...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2015 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Reformation Commentary on Scripture |

| Verlagsort | Lisle |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sonstiges ► Geschenkbücher |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Bibelausgaben / Bibelkommentare | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Bible • bible commentary • Book of Psalms • Commentary • Derek Kidner Commentary • Kidner Classic Commentary • Psalm • Psalms • Scripture • Tyndale Old Testament Commentary |

| ISBN-10 | 0-8308-9818-2 / 0830898182 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-8308-9818-3 / 9780830898183 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich