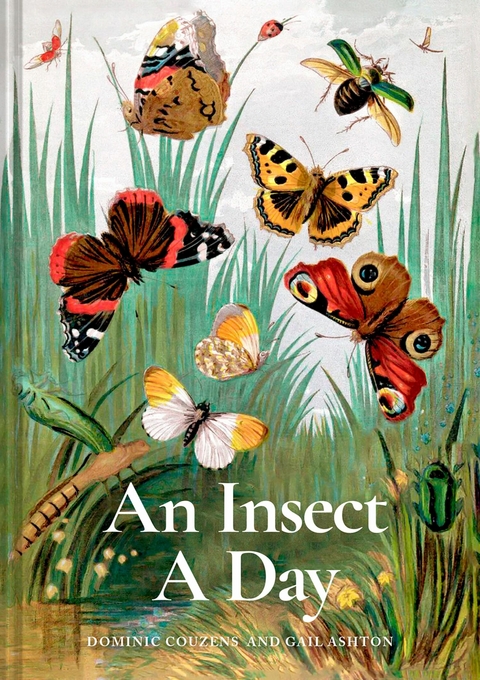

An Insect A Day (eBook)

368 Seiten

Batsford (Verlag)

978-1-84994-990-3 (ISBN)

Dominic Couzens is a British author and journalist specialising in natural history subjects. He contributes regularly to BBC Wildlife magazine and is a professional field trip guide. His critically acclaimed books include The Secret Lives of Garden Birds and The Secret Lives of Garden Wildlife. He is also the author of A Bird a Day, A Year of Birdsong and A Year of Garden Bees and Bugs. He lives in Dorset.

Dominic Couzens is a British author and journalist specialising in avian and natural history subjects. He contributes regularly to BBC Wildlife magazine and is a professional field trip guide. His critically acclaimed books include The Secret Lives of Garden Birds and The Secret Lives of British Birds, and The Secret Lives of Garden Wildlife. He is also the author of A Bird a Day and A Year of Birdsong. He lives in Dorset. Gail Ashton is a wildlife photographer and writer with a passion for entomology. A few years ago she began a year-long project to photograph and document 500 UK invertebrates, which sent her down a path of discovery that has become a passion. She is the co-author of the book An Identification Guide to Garden Insects of Britain and North-West Europe. She lives in Hertfordshire.

INTRODUCTION

Insects are everywhere, all the time, every day of the year. We might not see them on a daily basis, but they are still somewhere. They could be underground, in the sky or anywhere in between. Insects are permanent inhabitants of every continent on Earth. They still haven’t quite figured out the deep oceans, but everywhere else is fair game; insects have filled pretty much every available niche since their ancestors left the seas and made landfall around 480 million years ago. Of course, we are more likely to see them in warmer conditions, especially if we live in more seasonally extreme areas, because most insects are exothermic – requiring warmth and sunshine to function physically and metabolically. In temperate regions, insects will have more defined windows of phenological behaviour; that is, their reproductive and hibernacular cycles are tied to summer and winter respectively. In equatorial and sub-tropical regions, however, where there is little seasonal fluctuation, insects are active most of the year as temperatures and food sources are enduringly more favourable. Go towards the poles and insects spend most of the year in homeostasis, emerging for a period of weeks or even days in the brief windows of weak sunshine and relative warmth. The beauty of these climatic adaptations is that we can see insect activity nearly all the time, whether it be the warm hum of hoverflies in the spring garden, the ladybird snuggling up cosily into a hollowed plant stem in autumn, or the hippity-hop of snow-fleas across frosty moss in midwinter.

Before we commence our year-long odyssey, let’s remind ourselves what an insect actually is. Insects are classified in the kingdom Animalia, and within that the phylum Arthropoda, which is characterized by a segmented body, multiple pairs of jointed legs and a sclerotized (hardened) exoskeleton surrounding a soft body. Insects further distinguish themselves into their own class, Insecta, with a three-sectioned body (head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs of jointed legs and two pairs of wings, putting themselves in a different taxonomic group to similar arthropods, such as spiders and isopods. The subject of wings is something of a grey area, because not all insects have wings, and many appear to have just one pair, the other pair having long ago evolved into something else. The forewings of beetles, for example, have been modified into hard, protective covers beneath which they stow their hindwings. Flies’ hindwings have gone the other way, reducing down into tiny, clubbed stalks that seem useless but have evolved into super-sensitive sensory organs called halteres, which act as gyroscopes and send real-time flight and atmospheric data straight to the pilot’s brain. So, while we can’t always see wings in insects, what we can be sure of is that if it’s small, has wings and isn’t a bird or a bat, it’s definitely an insect.

Thousands of insects depend upon just a single plant species, or a few related species, to survive. The four-barred knapweed gall fly lays its eggs, as its name implies, in the seed heads of knapweeds.

Writing about insects has been, for two entomophiles, the easy part – for who could fail to be interested, intrigued, fascinated or even fixated with this group of animals? The hard part has been choosing which species to include, because the maths involving insects are truly staggering. One in two living creatures on Earth is an insect and they make up 90 per cent of all known animal species. The number of known global insect species currently sits at around 1 million, and it is possible that we are barely scratching the surface. Estimates fluctuate wildly between 2 and 30 million insect species on Earth right now, and that doesn’t include the many species that are becoming extinct before we’ve even discovered them. According to the Royal Entomological Society, there are around 1.4 billion insects per human on Earth; their mass outweighs humans 70 times. Other sources estimate that there could be 10 quintillion individual living insects on Earth as you read this – that’s a ten with 18 zeros on the end of it. We still don’t even talk about money or data in these terms: humans are lagging way behind with mere billions and trillions as a measure of hugeness. Social wasp nests can house tens of thousands of individuals, and termite mounds, hundreds of thousands. So how can our planet house so many insects when we humans are struggling to balance the ecological scales with a global population of 8 billion?

The sheer number of species of insects is remarkable. The elephant hawk-moth Deilephila elpenor is one of 1,450 species in its family Sphingidae, and one of 160,000 species of the order Lepidoptera, the butterflies and moths.

It comes down to size. We tend to measure success on scale – bigger is better and all that – but the foundations of this theory become very shaky when insects are brought into the picture. Insects used to be a lot bigger; take, for example, the gargantuan Meganisoptera of the late Carboniferous period, when atmospheric oxygen levels exceeded 20 per cent. These giant, dragonfly-like beasts had wingspans of 0.5m (½ft) and would give modern-day birds of prey a run for their money. This proved to be an unsustainable body plan, however, as a series of cataclysmic climate events and decreasing atmospheric oxygen levels wiped out the majority of species on Earth. The largest insects were pushing the limits of a successful body plan anyway (the rules of insect biomechanics can only go so far), so over hundreds of millions of years they became smaller, needing less food, water, free oxygen and space to survive. Combined with their short life span and prolific reproductive rate, which allow for rapid adaptation, insects have processed along a wildly successful avenue of evolution that brings us to the modern day, with an almost unquantifiable global population of insects, the diversity and variety of which is truly staggering.

It is so incredibly sad, then, that instead of admiring the success of the insects of Earth, we choose to demonize them. In the very short span of history that humans have occupied the planet (around 2 million years, a little shorter than the near 400-million-year occupation of insects), we have put our six-legged roommates in Room 101, the sin bin, the bad books. We blame them for everything from itchy skin to global food shortages, and our self-styled solution has been to kill them. It is our absolute conviction they are The Enemy, and thus we spend a disproportionate quantity of our time and resources obliterating them from existence, and this is a huge problem. We swat, spray, splat and squash them without really thinking about the consequences of this wholesale insecticide, because we only see the short-term benefits of having fewer insects bothering us. But learn more about insects, and look closely at them, and the veil of disgust will quickly fall away to be replaced with fascination, respect and yes, even affection. Because insects are beautiful! They are fluffy and have big eyes and they often look at you quizzically – they are basically tiny puppies. And many will sit happily on your hand; they can be very good company. They are superb parents, laying their eggs strategically, cleaning and tending their young and protecting them from harm, just like we do. And relatively, they don’t bother us at all. For every delirious, hypoglycaemic wasp that panics in our terrifying presence and stings us, and every fiercely determined female mosquito who desperately needs to catalyze her egg production with a blood meal, there are literally millions of other insects that never come near us and have no desire to do so, they just want to get through the day. Sound familiar?

Most of the species in this book will never cross paths with each other, or even be aware of each other’s existence, but they all share a strong bond, because they are all part of an expansive and intricate web of life, in which every individual insect plays a critical role. It may become food for something else; it may inadvertently assist in driving global food production through pollination services; it could be one of the recycling team that processes matter into soil nutrients, before its own body ends up as particles of loamy, nutritious compost. It might be one of a legion of predatory or parasitic insects, which naturally suppress population explosions, and scaffold food security within agricultural systems. It could even be one whose toxic biochemistry is being synthesized into the new generation of cancer-killing drugs. Every one of these roles is minor, but together they have formed the glorious, diverse, stable, habitable planet upon which we live today. I don’t know about you, but I think that deserves respect and kindness, rather than a fly swatter or the sole of a shoe.

It is with delight and pride that we present to you 366 insects and stories of insect folklore; one for every day of the Gregorian year – including that quadrennial leap day that offers us an extra 24-hour window and – in this book – a bonus opportunity to meet another incredible insect. Our selection contains six-legged ambassadors from all over the globe, all with astonishing adaptations. You will meet a ghostly butterfly that haunts the permanent twilight in the darkest recesses of the tropical rainforests and encounter a surprisingly resilient moth in the frozen Arctic depths. We also dive into the rich cultural fabric that binds us to insects through history via myth, legend and fossil record. If that hasn’t piqued your...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | A Day |

| Zusatzinfo | 366 illustrations and photographs |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Naturführer |

| Schlagworte | Almanac • Ant • BEE • Beetles • Bird a Day • Bugs • Butterflies • Butterfly • Cloud a Day • Entomology • flower a day • garden a day • garden pests • insect trivia • minibeasts • Natural History • Nature • Nature Table • pollinator • Tree a Day • Wasp |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84994-990-5 / 1849949905 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84994-990-3 / 9781849949903 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 30,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich