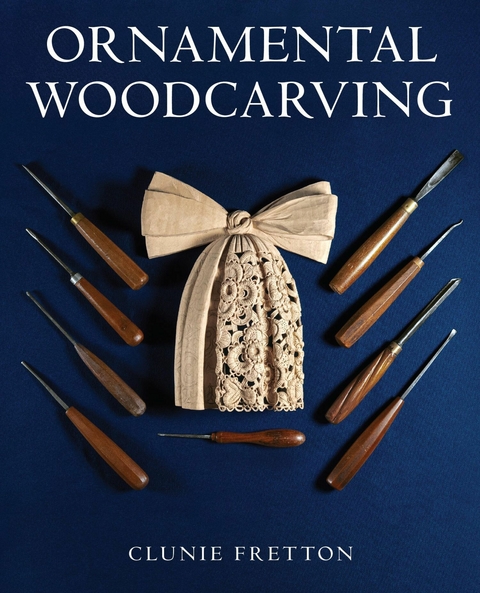

Ornamental Woodcarving (eBook)

192 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4437-9 (ISBN)

CLUNIE FRETTON is an award-winning, classically-trained master carver, sculptor and gilder. Her work is in the Houses of Parliament, the Victoria & Albert Museum, St George's Chapel Windsor, and museums, cathedrals and churches around the UK.

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Wood is one of the first materials mankind made into sculpture. There isn’t a culture or country in the world that doesn’t have a tradition of woodcarving, and to this day it remains one of the most ubiquitous materials from which objects are made.

St Anthony Abbot by Petrus Verhoeven, c.1800-c.1805. A sculpture in oak, depicting St Anthony Abbot in a thoughtful and naturalistic pose. The face, beard and hands are particularly sensitively carved. (Rijksmuseum, purchased with the support of the Stichting tot Bevordering van de Belangen van het Rijksmuseum)

The variety of colours, textures and shapes that wood comes in makes it a compelling material to work with. It’s not like stone, which formed millions of years in the past: to work with wood is to work with a material that has lived in your lifetime or the lifetime of your parents or grandparents. Some species of trees can survive for thousands of years, but when you work with a piece of timber there is a very real record of that life left behind. Wood has a grain, formed from the channels through which the tree drew water and nutrients, and when you cut across the trunk, the age of the tree is visible in its growth rings, swelling fatter in years of plenty and narrowing in years of hardship.

When you look at a piece of wood you can see the life the tree has lived: whether it’s suffered, or been starved of light from one angle, or been subjected to harsh weather. You can see where branches formed from the trunk and where they died or were lost and left knots behind in their place. Trees will grow around obstacles, and when they can’t grow around them they grow over them, engulfing anything from lead shot, to nails, fence posts and even bicycles that were once left leaning against them. Wood has the capacity to be both incredibly yielding to a carver, allowing us to create improbably fine and intricate sculpture, and also incredibly resistant. It doesn’t work with you – you are forced to work with it, and there is no point at which you’re able to forget that it was once a living thing. It imposes itself every time you make a cut, requiring a particular angle of working and a bewildering variety of tools with which to do so; it swells and moves and shrinks depending on the temperature and humidity; and its colour and vividness alter and develop with age.

A tree grows up through a neglected drystone wall. The trunk has partially engulfed the coping stones, lifting them free as the tree grows taller.

It is, in short, both a tremendous pleasure to work with and at times a difficult thing to do. It has the virtue of accessibility, in that almost anyone, anywhere, can find a lump of it and something sharp with which to cut it, but it can be hard to bridge the gap between that very direct kind of carving and the more intricate traditions of woodcarving. It’s my hope that this book will provide a solid basis from which you can develop your own practice.

Though every culture has its own tradition of carving, the tools and techniques differ considerably between them. All traditions are equally viable methods of working wood, and often reflect tools and techniques developed specifically as a result of the particular qualities of a country’s native timbers. This book will focus on the European tradition of woodcarving (and in some cases specifically British), which is the tradition in which I’ve been trained and with which English-language speakers are likely to be most familiar.

One cannot discuss carving without also discussing ornament, and each carving tradition is intimately intertwined with its ornamental lexicon. There has naturally been a great deal of cross-pollination over the years, with motifs like the Green Man – something many consider to be quintessentially European – appearing or perhaps originating as far away as India. However, there are recognisable and distinct styles of ornamental carving across the world, and part of the joy of carving is in recognising these motifs and their variations, and the identity they give to objects, furniture, buildings, and the people who made them. Carving offers a visual record of our history, both joyful and terrible, and reflects the preoccupations of the people at the time. One only has to look beneath the seats at the misericords (brackets or ledges on the underside of choir stall seats) of Medieval churches to see both the fears and the (often rude) humour of the carvers working on them, and the damage left by the iconoclasts who came after.

When one looks at a carving, it’s possible to see both the small and intimate picture of the individual tree it was made from and the character of the person who worked it, as well as the larger picture of the society in which they lived, and the environmental record of the climate and time expressed in the body of the timber.

In carving something yourself, you agree to do more than just make an object. You contract to work with a particular wood, the species of which will make differing demands upon you; you agree to examine the object that you wish to make extremely closely, and in much greater detail than anything you might stop to look at in a gallery or museum; and in doing so you leave a lasting legacy in the world.

Woodcarving is inherently a slow activity. If you decide to create a sizeable or complex carving you may end up working on it for months at a time. We live in a time where objects are manufactured increasingly swiftly and replicated even more so. When you work with a material that has taken decades or even centuries to reach you it’s important to take the time to make something worthwhile from it.

Carving as a practice involves both more immediacy and more patience than most other activities, and though it takes longer to produce, the absolute attention demanded by the combination of physical and mental decision-making can make the hours disappear.

Wood and stone carving have long fallen under the shadow of being a ‘dying art’, but while much has been lost, the profession is no means dead. The more people who carve and the more ubiquitous ornamental carving becomes, the more awareness there will be and the greater the demand for it. The greater the demand, the greater the standards and innovations. We have entered an unprecedented place in our recent history – a place in which the abandonment of ornament that accompanied modernism means we no longer have a distinctive ornamental style. Rather than being dispiriting, this should be something exciting: an opportunity for new carvers to learn from the best the past has to offer and to leave behind their own stamp on history.

CARVING TODAY

There was once a time when every city in Europe boasted carving workshops, each employing dozens of carvers producing work to sate the vast appetite for sculpture and ornament. Go back even a hundred years and you’d find a large number of active workshops working to that scale. Nowadays there are almost none. Over the last sixty years, carving workshops that had run for generations have closed, and the continuity of training that saw an apprentice train under masters, becoming a journeyman and then a master himself, has broken. It’s extremely rare in Britain to find workshops employing more than five to ten carvers at most, and much more common for carvers to work alone.

This scaling down has offered flexibility and resilience that has allowed the craft to weather the tide of changing tastes, but in doing so it has traded in a lineage of skill that passed directly from master to apprentice. Unlike trades like gold beating or damask weaving, woodcarving is currently considered viable in the UK according to the Heritage Craft Association’s Red List of Endangered Crafts, with one institution teaching a fulltime course and a number of practising carvers offering short courses, but the changing conditions raise the question of what it means to be a carver in the present day when the vast well of resources that were available to our predecessors as part of daily life are absent to us.

The picture nowadays is very different from the one even a hundred years ago. In the past most carvers were apprenticed young, and often entered a family business. They would have grown up surrounded by carving, watching how tools were used and pieces constructed, how ornament was designed and how distinct styles were implemented, and would realistically have been expected to master only the style of carving that was in vogue at the time. If a carver showed a proclivity toward a particular element in that style, he might spend the bulk of his career specialising in a particular type of ornament, building up such speed and familiarity with the form that the carving could be done without even a reference at hand. Large workshops encouraged these kinds of specialisms, as it allowed a master to create the design and each man to work on the subject with which he was most proficient. A large workshop would have carvers who specialised in particular kinds of ornament and others who worked figuratively, some who were particular specialists in faces, and all of these carvers worked collaboratively on larger projects.

The carving workshop of E.J. & A.T. Bradford, once at 62–63 Borough Road, London SE1. Master Carver Tony Webb, one of the last indentured carving apprentices in the UK, served his five-year apprenticeship there from 1952. In the centre, Tony Webb, and behind him wearing the tie, Robert Banks, both future Presidents of the Master Carvers’ Association. (Tony Webb)

A journeyman (Charles...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten |

| Schlagworte | Carving • Cathedral. • chisels • Classical • craft • Heritage • heritage craft • learn woodcarving • master carver • Museum • Ornament • ornamental • ornamental woodcarving • sculpture • sharpening • Traditional • wood carver • woodcarver • wood carving • woodcarving • woodcarving classes • wood sculpture |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4437-1 / 0719844371 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4437-9 / 9780719844379 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 91,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich