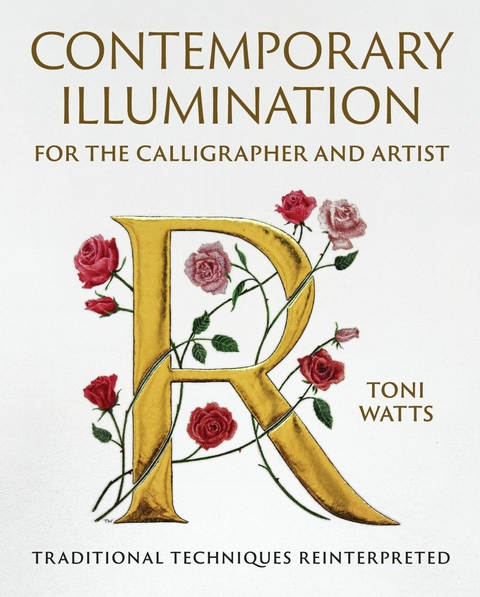

Contemporary Illumination for the Calligrapher and Artist (eBook)

176 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4429-4 (ISBN)

TONI WATTS is an internationally-recognised illuminator, and one of the few artists still using traditional manuscript gilding skills. She creates new work using age-old techniques and hand-prepared, natural materials. These include mineral and earth pigments, plant pigments from her garden, traditional handcrafted inks, vellum, 24-carat gold leaf and gemstones such as sapphires and emeralds. She specialises in manuscript illumination, but also draws with metalpoint and paints in egg tempera. Toni has had a diverse career - she worked for over twenty years as a doctor while pursuing a career as an award-winning wildlife artist. She then gained a master's degree in art history, which sparked an interest in medieval manuscripts and the trade in pigments. This led to a year (2015-16) as artist-in-residence at Lincoln Cathedral, where she had the opportunity both to study its collection of manuscripts and create a new body of work. She now runs national and international workshops on manuscript illumination.

Contemporary Illumination gives detailed instruction for artists wishing to add gold leaf to their work. It explains the techniques used in medieval manuscripts but shows how these same techniques can be used to stunning effect to enhance lettering and paintings in contemporary styles. Alongside step-by-step instruction, it also gives practical advice on how to fix common problems. For both the novice and the more experienced, this handsome book unlocks illuminated secrets from the fifteenth century and shows how they can be applied just as beautifully to art of today. With fully illustrated step-by-step instructions for gilding and painting using readily available off-the-shelf products. For those with more experience, there are detailed instructions on the making and use of both manuscript gesso and shell gold, with examples of how they might be used both to enhance a calligraphic text as well as a painting or drawing. There are also suggestions of how to paint on gold, and how to combine flat and raised gilding in new and innovative ways. This book is a visual treat and an invaluable guide for everyone who wants to appreciate the art of illumination and to learn how to use traditional techniques in contemporary applications.

INTRODUCTION

I work, often in silence, coaxing fluttering leaves of pure gold onto a prepared page. The gold catches the light as it turns, a flash of fire in the cool of the morning. It settles into place and I polish it to bring out the shine. The burnished areas look like droplets of liquid gold, reflecting the light of the new day.

WHAT IS ILLUMINATION?

To ‘illuminate’ means simply to ‘light up’. It comes from the verb illuminare, from in- ‘upon’ + lumen, lumin- ‘light’. This book is about ‘the decoration (of a page or letter in a manuscript) by hand with gold or silver’, a definition helpfully supplied by the Oxford Dictionary. I’ll leave gilding on canvas, stone, panel and wood to other authors.

Pages throughout the centuries have been adorned with gold. The practice isn’t restricted to one faith or one continent. Buddhist scrolls from Japan were sometimes written in gold, as were many exquisitely decorated versions of Islamic Qur’an. The pages I’m most familiar with, though, are the Christian illuminated manuscripts of the European medieval era.

Holding a medieval manuscript is a tactile, and very human, experience, so different from looking at isolated digitised images. These books are gloriously and unashamedly handmade. Old wooden boards, corners rubbed smooth from centuries of use, enclose pages of vellum. Some are so thin as to be translucent, some so thick that they creak as you turn the page. Each page is painstakingly hand written, with a quill that had to be cut from a feather and continually resharpened with a pen knife, and ink made from oak galls. You can see, sometimes, where the scribe has tired at the end of a long day, with letter forms becoming less than perfect. There is the occasional misspelling. Some words have been missed out altogether and added later. Sometimes you can clearly see that the scribe had a tremor, his hand shaking as he tried to write.1 Unofficial illustrations in the margins may puzzle us or make us smile.

A beautiful illuminated manuscript from the Lincoln Cathedral library.

But it is the gilded elements that are striking. No matter how small the area, there is something captivating about the light catching gold as each page is turned.

A little pen and ink drawing in the margin of one of Lincoln Cathedral’s manuscripts.

An illuminated letter P from Lincoln Cathedral MS 145. You can see that the manuscript has been trimmed and rebound sometime in its past.

For medieval artists in Europe, working within the Christian faith, gold represented spiritual light. As the centuries passed, it also came to signify wealth, with manuscripts becoming increasingly decorated with gold, expensive pigments and precious stones. We now live in a digital era where the majority of books are not hand made and where lettering is generated by fingers tapping on keyboards and screens.

COPYING MONKS

A student, when introducing herself to me in a workshop, once said, ‘My calligraphy tutor won’t teach me illumination. She says there’s no point in copying medieval monks.’ I was (unusually!) lost for words for a moment.

The various tones of malachite and azurite pigment extracted from rough minerals.

Plants and minerals that can be made into paint: weld, buckthorn berries, marigold flowers, malachite and azurite. If buying minerals, do give consideration to their provenance. There are ecological and humanitarian issues in some mining areas.

To be fair, I’ve done my share of ‘copying monks’ over the years. I’ve read translations of old manuscripts dealing with gilding. I’ve learnt how to make ink and transform minerals and plants into the beautiful paint colours that survive on pages decorated 800 years ago. I can create an illuminated page using only the materials and tools available to a fifteenth-century illuminator.

But now I use those age-old techniques to create new work. Styles of illumination changed between the eighth and fifteenth centuries, waxing and waning in popularity. I’m now creating work which reflects the era in which I live. Some of that work is text- and manuscript-based. I enjoy painting wildlife, and gilded elements have found their way into that work too.

LEARNING

Any craftsperson will tell you that it takes steady practice to master the old skills. I also believe that it requires good tuition. After all, you wouldn’t expect to be able to drive a car without having a driving instructor, or make a soufflé without someone showing (or at least telling) you how. Manuscript illumination has the reputation of being ‘difficult’. It isn’t. It’s a skill that can be learnt, like any other.

I had some long conversations with my students when I was trying to decide whether to write this book. After all, there are already some excellent volumes on the market, with stunning examples of illuminated work and ‘step-by-step’ examples. Could I really add anything to what is already available? The general consensus was that I could. ‘The difference,’ said one student, ‘is that you teach us how to fix our mistakes. You tell us what to do when it all goes wrong. The other books just assume that eveything will turn out perfectly. You teach us how we can improve.’

‘Fixing mistakes’ is what we all do, all the time. The soup doesn’t taste good? Add a bit more salt next time. Illumination isn’t any different.

TEACHING

Why do I teach? Because I love it is the simplest answer. But I also feel strongly that I should pass on my knowledge, if illumination as a heritage craft is to survive. At the moment it is classified as ‘endangered’. What does that actually mean?

According to the website of the Heritage Crafts Association, a heritage craft is defined as ‘a practice which employs manual dexterity and skill and an understanding of traditional materials, design and techniques, and which has been practised for two or more successive generations’. Their Red List of Endangered Crafts, first published in 2017, ranks traditional crafts by the likelihood they will survive to the next generation. An endangered craft is one which currently has enough craftspeople to transmit the craft skills to the next generation, ‘but for which there are serious concerns about their ongoing viability’. Put simply, there aren’t enough of us – illuminators using traditional techniques – to ensure the continuation of this beautiful art form. And that seems a shame.

ILLUMINATION IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Over the past 15 months, whilst I’ve been writing this book, I’ve seen a move in both calligraphic and art circles from ‘traditional’ to ‘expressive’ work. Most of my students, whether they be artists or calligraphers, don’t want to re-create medieval designs. They want to make something contemporary and personal. They want to be inventive.

I believe there is room for both: an honouring of the craftsmanship of the past and a spirit of twenty-first-century experimentation. I’ve tried to include a little of everything in this book, with the understanding that not everyone will like every example. I’ve done comprehensive tests of all the gilding sizes currently available in the UK but haven’t found anything I like better, for my own purposes, than those which were available to medieval illuminators. I’m sure you’ll find your own favourites.

Gold laid on manuscript gesso, burnished to a mirror shine.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

The majority of books on illumination have a calligraphic basis, with gilding examples drawn from the changing styles of illuminated letters over the centuries. This one is different. My chapters aren’t labelled Gothic, Romanesque, Celtic and so on, but Gums, Gesso and Shell Gold. It’s a technical book showing what you can and can’t do with each gilding size and what you can (and can’t!) fix when things go wrong. That means there is some overlap in terms of result. You can, for example, glue your gold flat to the page with gum ammoniac, thinned Miniatum, an acrylic size or garlic. You can make your gold raised by gilding on gesso, Instacoll or Water Gold Size. Each will give you a slighly different result and each will have its own challenges. Which you use is a matter of personal preference.

There are ‘step-by-step’ examples in all the early chapters, but not, for example, in ‘Writing with Gold’. I’m essentially an ‘illuminator’ rather than a ‘scribe’ – medieval artists generally were one or the other. My job is not to teach you how to write. There are many expert calligraphers better suited to that task.

As an illuminator, I walk in the footsteps of all those have gone before me. Henry Baundeney, ‘Henry the Illuminator’, worked in Lincoln in the thirteenth century, in a property on Lumnour (or Luminor) Lane.

As I walk up Steep Hill to the Cathedral, with what was Parchemingate, the street of the parchment makers, set off on my left, I think how lucky I am to be continuing this tradition. I hope you enjoy your walk through the various illumination techniques in this book and that,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Malerei / Plastik |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Schlagworte | calligraphy art • Gesso • gilding • gilding art • Gold • gold leaf • gold leaf art • gold leafing • heritage crafts • Heritage skills • illuminated manuscript • Illumination • Illuminator • learn illumination • Manuscript • manuscript gesso • Manuscript Illumination • medievalillumination • shell gold |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4429-0 / 0719844290 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4429-4 / 9780719844294 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 74,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich