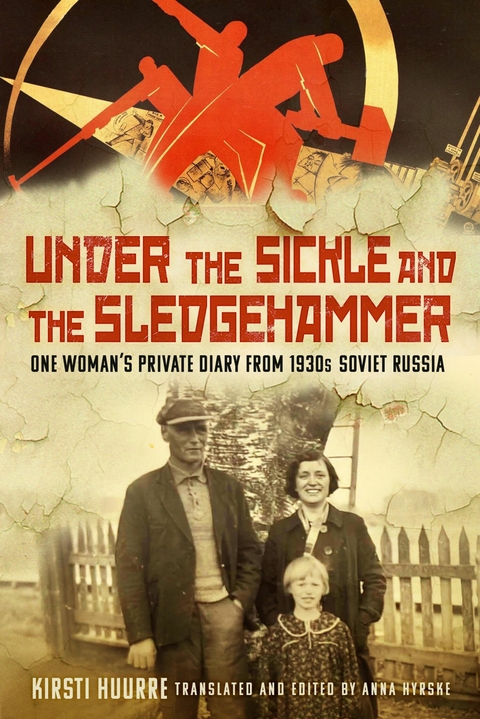

Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer (eBook)

232 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-670-7 (ISBN)

KIRSTI HUURRE was the author of the original memoir, Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer: One Woman's Private Diary from 1930s Soviet Russia.

Introduction

by Anna Hyrske

Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer (Sirpin ja moukarin alla) was originally published in 1942, as war was still raging between Finland and the Soviet Union, the outcome still unknown. (Finland was to remain independent but at the price of losing vast areas.) Subsequently, in 1944, with the Allied Control Commission (ACC) making demands on the Finnish government across a number of areas, the book fell victim to a rigorous Soviet-led censorship of literature. The ACC was controlled by its 150–200 Soviet members (Britain, for example, had only fifteen seats); in official communications its name was often displayed as ‘Allied (Soviet) Commission’, highlighting where the supremacy lay.

The Commission began its work in September 1944, and it lost no time in rolling out its book censorship programme. By October that year, publishers, bookstores and libraries had been contacted with the aim of curbing access to literature that could be considered detrimental to relations between the two countries.

A list of around 300 proscribed titles, Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer among them, was distributed to Finnish bookshops; the books were to be removed from the shelves and returned to publishers. Libraries across the country also received letters to demand the withdrawal of titles that might have been damaging to Soviet–Finnish relations, but it did not specify any titles: librarians had to judge for themselves. According to Kai Ekholm’s The Banned Books of 1944–1946, a PhD thesis published in 2000, the range and quantity of books varied significantly between libraries: most libraries withdrew books in their dozens whereas the Helsinki City Library removed 4,000 volumes. Ekholm’s research reveals that Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer was banned by 267 local governments during those years (out of around 400 at the time), second only to Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, which was deemed unacceptable in 292 localities. It wasn’t until 1958 that researchers had access to the book, but only by asking a librarian to fetch it from the so-called ‘poison cabinet’ – the name given to a locked cabinet housing literature perceived as too dangerous for general consumption. I have seen copies containing an inscription made by the Finnish military in 1942–43: apparently, the book was awarded as a prize for outstanding achievement, presumably on account of its potential to further encourage anti-Soviet sentiment, which goes a long way to explain why the Soviet Commission was so keen to blacklist it.

Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer starts in 1932, seven years before the Winter War was to erupt and fourteen years after the Finnish Civil War. Finland had gained its independence peacefully from Russia in 1917, in the aftermath of the October Revolution and the downfall of Imperial Russia. The proletariat in Russia had enough to do maintaining stability within their own borders, and Finland seized the opportunity. For a little over 100 years prior to its independence, Finland – or rather the Grand Duchy of Finland – had been an autonomous state within the Russian Empire with its own currency and legislative structures. And for several hundred years before 1809, which marked the end of the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, Finland had been part of Sweden.

Although Finland didn’t actually fight Russia for its independence, that is not to say the transition from Grand Duchy to an independent state didn’t involve bloodshed. Less than two months after the declaration of independence, civil war broke out between the ‘Reds’ and the ‘Whites’. Finland had undergone massive social change – population growth, urbanisation, resettlement – and these destabilising trends, coupled with the impacts of the power struggles of World War I, led to two polarised forces fighting for supremacy. The Reds represented a socialist world view and wanted the government to be formed by one proletarian party; the Whites had no common political view other than opposition to communism and socialism. The Whites were better equipped and had a greater number of professional combatants, and this afforded them the upper hand in war conditions. The Civil War was brutal – especially for the Reds. Casualty numbers in conflict were similar on both sides, but the Reds also suffered major losses through executions, deaths in captivity and those ‘missing in action’. Some reports claim that 12,500 Red lives were lost within prison camps compared with a White toll of merely four. This goes some way to explain the rawness of feelings – the emotional and physical wounds – within Finnish society in the early 1930s, with many of the crimes of the Civil War left unpunished. Indeed, the Civil War and its aftermath very likely acted as a catalyst for the effectiveness of Soviet propaganda promising a better life, better jobs and better housing across the border. Throughout this book we encounter characters who have traversed that border, and, as often as not, the question is asked: did they arrive legitimately or did they use clandestine means? The conversations we hear in this book suggest that many of those travelling without a passport had been previously interned in one of these prison camps. Kaarina herself, the narrator of this story, tells of having occasionally visited a friend in such a place. Others had apparently spent time in hospitals in conjunction with their term in a camp, the implication consistently being that conditions in the camps were harsh. This is a highly plausible motivation for wanting to find a more equitable place to live.

Despite having friends who fought against the Whites, and despite being intrigued by the proletariat movement in Russia, Kaarina was not active within the Reds; nor was her family. On the contrary, her father was a businessman with dozens of employees and a centrally located store selling tailor-made men’s and women’s clothing. Interestingly, the Helsinki city-centre building where he ran his business is today the home of a Louis Vuitton store. Kaarina’s first husband, and father of her son Poju, had a butcher’s shop in central Helsinki. He was not a communist supporter, so her interest in the utopia of a workers’ paradise must have been fuelled by outside influences, such as pamphlets, adverts, meetings and conversations with those who had already crossed the border or were planning to cross.

I have been aware of this story since my late teenage years because it was written by my great-grandmother. She is the Kaarina and the narrator of this harrowing tale, although for good reason she published under the pseudonym Kirsti Huurre (all the names in the story have been anonymised). The Poju in the story is my grandfather, and he is still alive. I have had the opportunity on a few occasions to talk to him about his mother’s life choices and their outcomes. He read the original version at some point in his life, but only once. He agreed without hesitation to my suggestion of translating and editing it. To him, though, it is simply part of his own life story, and he finds it intriguing that others might be interested in it! I never had the chance to meet my great-great-grandfather (Kaarina’s father in Helsinki) but I have some pictures of me as a baby with my great-great-grandmother. My great-grandmother Kaarina remained a distant character, living out the remaining years of her life in Sweden for fear of being deported from Finland as a Soviet citizen.

I have been toying with the idea of translating this story into English for a very long time because I believe it’s a story worth sharing. But it was the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 that propelled me into action, convincing me that this story really needs to be retold and brought to light once again. The Russian approach of vilifying its neighbours, the fake information used to justify an attack – it is all disconcertingly reminiscent of what happened in the 1930s. Then, just as now, it’s the general population – the ordinary people – who suffer from the decisions made by people clinging to power. My great-grandmother took at face value the narrative that was being circulated by some Finns or their Soviet comrades: power is in the hands of the working class, access to fulfilling work and good-quality housing for all, and your role in society is not determined by money or family background. By the time she’d seen through all the layers of propaganda, it was too late. In the book she conveys how the Russians ardently believed in this ‘freedom’ as something to strive for, but in the face of all the evidence still failed to realise that it was no such thing. Those who had imigrated to Soviet Russia from abroad, such as Americans or her fellow Finns, were able to take a more objective view and make comparisons with what they had left behind.

A modern English-speaking reader can at times feel quite distant from the book’s original Finnish audience, both historically and geographically. In acknowledgement of this, I have added a few footnotes where I thought an explanation might help. There are many place names, which as well as being potentially unfamiliar, have both Russian and Finnish forms. Even the book’s title requires some explanation. It is not ‘the hammer and sickle’, the customary emblem of the Soviet Union, but rather a deliberate play on this: the word ‘sledgehammer’ was chosen to emphasise the violence, force and power exerted over members of the population who didn’t fit into the mould, came from the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Schlagworte | 1942 memoir • authoritarianism • bolshevik party • censored book • communism • communist • communist purge • communist revolution • Finalnd • finnish book censorship • finnish soviet war • Great Purge • Great Terror • great wraths • Josef Stalin • joseph stalin • Karl Marx • Leiba Bronstein • Leon Trotsky • Rebellion • Russian Revolution • secret memoir • soviet memoir • soviet propaganda • soviet purge • stalins russia • state propaganda • Under the Sickle and the Sledgehammer • USSR • war memoir • winter war • World War 2 |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-670-6 / 1803996706 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-670-7 / 9781803996707 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich