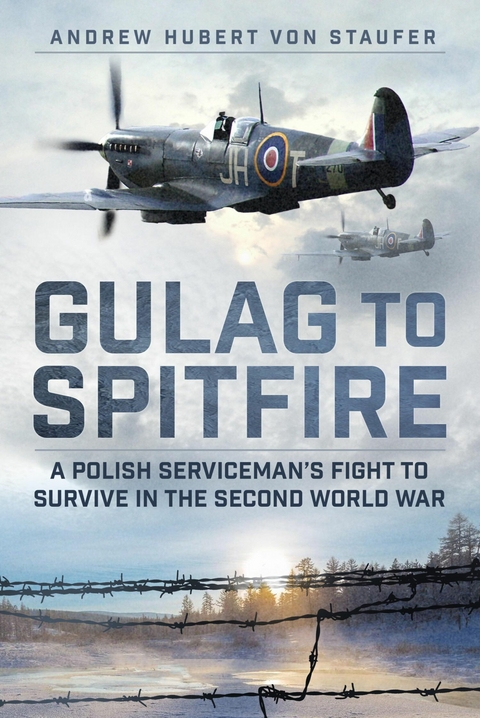

Gulag to Spitfire (eBook)

288 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-522-9 (ISBN)

1

The Realities of War

Getting back to his home in distant Lwów1 turned out to be far more complicated for Tomek than his arrival at the gliding club. The instructors were going in a completely different direction and Tomek soon discovered that if he was going to get home, it would be entirely by using his own resources.

He had been dropped by what passed for a main road and pointed in the general direction of his home town nearly 200km away. The weather was hot and he was thirsty. He saw a couple of military lorries going in the opposite direction and his wave was met with little response. The faces that stared out looked strained and resigned. For the first time his natural self-confidence was beginning to ebb away.

A policeman on a bicycle stopped Tomek and asked for identity papers. This was unusual and he argued back. The policeman just shrugged: ‘It’s war.’ He pointed out that, having given his name as Tomek, his identity card recorded him as Kazimierz Tomasz Hubert: ‘Stick with Kazimierz, whatever they call you at home. Some of the militia are very nervous, shooting at anything that worries them. There are all sorts of stories going about infiltrators and German soldiers parachuting down dressed as nuns. Everyone is in a panic. Keep your story simple. You don’t want to be shot by accident.’

Tomek was now beginning to get very worried.

A farmer took pity on him, giving a lift in a hay cart. He had no idea what was going on, but told Tomek that he reckoned that the war had either started already or would begin in a matter of hours. He passed that first night in an outhouse having eaten black bread and quenched his thirst with flat yeasty beer.

The next day he fared slightly better at hitching lifts but even so the journey was tiring, depressing and often lonely, with no chance of phoning ahead to let his mother know he was OK. He had never thought of it before, but the countryside was so empty. Not all the hamlets were Polish as some of the poorer farms were owned by Jews, who clustered together for mutual support and, unlike the polyglot population of his home town, tended to be insular and fearful of strangers. For the first time Tomek had the uncomfortable feeling that maybe those in charge, like his late father, should have been more open to the realities of this part of Poland and not so obsessed with rallying nationalist feeling behind the shield of a Polish version of Roman Catholicism, where national identity, statehood and religion made an uncompromising and probably toxic mix.

He was tired, smelly and in pain by the time he reached his home, thirty-six hours after leaving the club. If he had hoped for a warm and sympathetic welcome, he was out of luck as his older sisters were already in uniform and, far from listening to him as the man of the house, they were preoccupied with orders they had received by phone.

His mother wasn’t really bearing up to the strain. Still unsure what was going on, he turned on the radio the next morning hoping to hear a news bulletin. Instead there was static, interrupted occasionally by what sounded like grid references, and what he guessed to be coded movement orders.

Things were not much better when he reported to the city hall. There were queues of young men and women. Nobody seemed to know what was going on. Finally his old Scout master spotted him and pulled him out to join a few younger lads who looked terrified. Within an hour they boarded a bus that took them westwards to a tented camp, where they drew very uncomfortable, ill-fitting uniforms.

Tomek might have expected to be given some sort of enhanced training or fast track, given his family background, but any hope of being an officer cadet, trainee pilot or even using his experience in ham radio disappeared within a matter of days. He was told he would be assigned duties once he reached a forward position.

It was now obvious that the only training was that of surviving in the crucible of war.

In that late summer of 1939, Germany was well prepared for invading a Poland that Hitler argued should not exist. Even his arch rival and equally cruel despot, Stalin, could agree with that. Stalin was once quoted as saying: ‘The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.’ There was little doubt that an independent Poland would not be allowed to survive.

Hitler’s ‘experten’ were pilots who had the advantage of lessons learned supporting Franco in the Spanish Civil War. The Poles had no chance of achieving air superiority over their home soil. Their PZL P.11s were at least 30mph slower than many of the German bombers and too lightly armed to knock them down with anything less than a very long machine-gun burst at very close quarters. When it came to taking on the Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, the P.11s, known as Jedenastka by the Poles, were almost 100mph slower.

Tomek didn’t really appreciate how badly equipped the Polish Air Force was until his reserve training unit was surprised by a P.11 landing in a rough field near their tents. The heavily muffled pilot got out, took off a helmet and unwrapped a scarf to reveal it was a girl not much older than himself, who asked to see their maps as she had lost her way and had no radio. He watched her take off again and for the first time realised that they probably wouldn’t win.

The next day, he was given a map and a grid reference and told to take a group of younger lads in leading several horse-drawn waggons to another camp about 30km away. It was now obvious that they were heading towards where the war was being fought.

He had heard the German Stuka dive bombers in the distance, their sirens shrieking as they bombed villages and columns of both soldiers and refugees. Their sirens, known as Jericho Trumpets, were designed to cause fear and panic. Even at this distance, the effect made his unit’s horse-drawn transport scatter. Many of the reserves were nervous, diving into ditches at the sound of any approaching aeroplane, then spending anything up to an hour trying to re-muster the horses and set off again along the road before the whole chaotic carousel began again.

Tomek was shocked the first time he came across a column that had been bombed. As he later told my mother, the smell made him gag and retch. Horses lay on either side of the road, some with limbs blown off or almost eviscerated by the blast, while others plainly had been put out of their agony by a single bullet wound to the head. Wounded men had already been removed and temporary graves littered the surrounding field. From now on things changed rapidly.

A very worried-looking man in uniform, who announced he was a medical officer, arrived in a large car and asked for volunteers. Tomek was among the first, thinking he was about to see action at last. To his surprise he and five others were taken off to the east, away from the still very distant fighting, in the direction of Lwów. They had barely gone a few kilometres when a farmhouse in the distance seemed to mushroom, instantly exploding into an expanding boletus of mud, dirt and clouds of smoke. The blast hit a second later. Tomek had never experienced anything like this before. It slammed the breath out of his body. The officer continued driving and didn’t appear to flinch. One of the younger boys on the back seat was now crying.

The officer turned to Tomek. ‘Can you drive?’ Tomek shook his head. ‘I suggest you watch me, you’ll have to learn quickly.’

The next week was spent moving to one place then another without being sure where they were or what they were supposed to be doing. This was complicated by columns of refugees blocking the roads as they moved east. Many of them were orthodox Jews, women with their heads covered in scarves or something that looked a bit like a turban, while the men wore long black coats and wide-brimmed hats, despite the heat, and curls in ringlets down the side of their faces. Those who were not showing signs of fear were stone-faced. Women and children were crying; from a distance it sounded like a constant, nerve-jangling, keening wail.

An old sergeant at a crossroads looked grim. ‘Poor bastards, I’ve heard stories of mass executions by the Nazis. They’ll be the first to go.’ Tomek later heard that some of the younger men had shaved off their curls, ditched their wide-brimmed hats and headed into the forests, saying they’d fight the Germans. This was greeted by the dismay of their parents, who were afraid it would only make matters worse for them.

Not yet knowing how far the Nazis were prepared to go in their hatred of the Jews, this didn’t make a lot of sense to Tomek. Sure the Jews were always a people a bit apart, but by and large they were no threat. They usually played the best music at weddings and sold the best bargains at the market. Although they spoke Polish, they preferred to converse in Yiddish or even Russian. Tomek wasn’t too sure about this, as sometimes he thought they were talking about him. Even so, he never met one in the Scouts or among the reservists.

His first field hospital was another shock: one doctor, two orderlies and more than 200 patients, many of them dying with horrendous injuries. He had not realised before, but blood and spilled guts smelled.

Not having any real medical experience, his first task had been to bury the dead in their makeshift graves. Every morning there were more, every afternoon ever greater numbers of wounded appeared. Those capable of walking were sent on while the worst were given morphine, if available, to kill the pain and wait either for them to get better...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.8.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 16pp mono plate section |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | angela oakshott • Bletchley Park • GULAG • Kazimierz Tomas Hubert • life in a gulag • Life in the Gulag • Luftwaffe • Lwów • nkvd • no 317 polish squadron • poland in world war two • polish RAF • polish servicemen • Second World War • Siberia • Spitfire • stalin's siberia • Tehran • Tomek • vorkuta gulag • World War Two • ww2 • WWII • yalta agreement |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-522-X / 180399522X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-522-9 / 9781803995229 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 19,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich