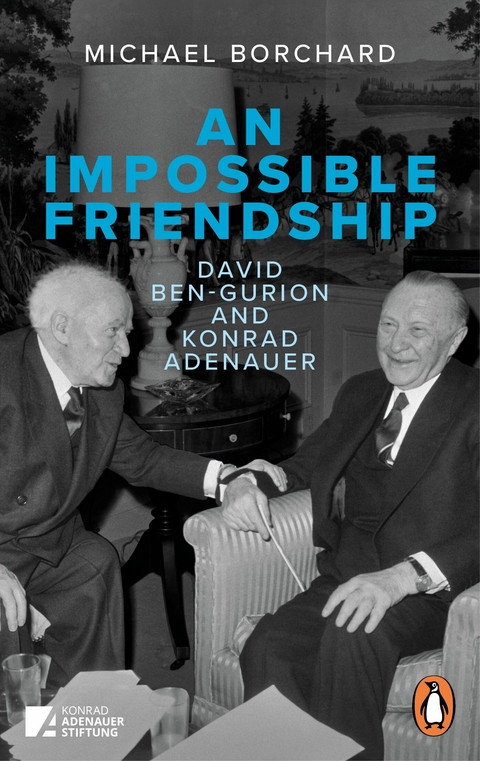

An Impossible Friendship (eBook)

464 Seiten

Penguin Verlag

978-3-641-32817-7 (ISBN)

David Ben Gurion and Konrad Adenauer stand as stalwarts of 20th-century politics, their legacies linked through German and Israeli history, revealing striking parallels. Despite ascending to the pinnacle of political power relatively late in life, both emerge as architects of a new statehood for their respective nations, carrying out pioneering work both domestically and on the diplomatic stage. Their bond deepens into friendship although they only met face-to-face on two occasions.

Michael Borchard recounts the intertwined lives of Ben Gurion and Adenauer in parallel, illuminating their seemingly impossible friendship and prompting reflection on the contemporary lessons that can be derived from these two towering figures.

With a foreword by grandsons Yariv Ben-Elieser and Konrad Adenauer.

- Erste englischsprachige Übersetzung

- Ein wichtiger Teil der deutsch-israelischen Geschichte

- Politisch und gesellschaftlich bis heute höchst relevante Doppelbiografie

Born 1967 in Munich, Dr. phil. (Ph.D.), studied Political Science, Contemporary History and Public Law at University of Bonn, 1989-1994. Former member of the team of speech writers for the former Federal Chancellor Helmut Kohl and head of the speech-writing division for the former Ministerpresident of the State of Thuringia, Bernhard Vogel. From 2003-2014 director of department 'Politics and Consulting' in the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS). 2014-2017 resident representative of KAS in Israel. Since 2017 director of the department 'References and Research Services/Archive for Christian Democratic Policy' in KAS and as such responsible for the documents of the CDU.

Konrad Adenauer and His Relations with the Jewish Community

Scholars and journalists have speculated time and again just how sincere the German federal chancellor’s engagement for reconciliation between Germany and the Jews, and for rapprochement between Germany and Israel genuinely was, on balance. Of course, his innumerable statements on the moral duty to contribute to the survival of Israel with financial benefits have been heard, but they are hardly ever reported without a demonstrative reference to Adenauer’s pragmatism, his astuteness, and his determination to use the relations with the Jews and with Israel to buy the ‘ticket’ that would allow Germany to become a respected member of the international family once again. How great was this need really, and how great, correspondingly, the factor of ‘calculation’ – and how great, conversely, was the sense of moral duty; how great, indeed, was Adenauer’s appreciation of Judaism and the Jews and, consequently, for Israel?

This may be the most banal of all characterisations of the great Rhinelander, but it is accurate: Konrad Adenauer was a multi-layered character and is not easy to grasp. A politician who could be a master of discrimination and reticence but also a ruthless champion of the interests he considered to be politically right. Adenauer was a strict moralist and at the same time a man of Rhenish liberality. He was a pious Catholic believer, ‘God-fearing’ in the better sense of the word, and yet never an unquestioning obstinate believer in hierarchical structures. He was able to engage critics and sceptics as well as employing his untrammelled assertiveness. He wanted to ensure that the dark years of National Socialism were behind Germany and to start a new chapter, while remaining sceptical as to how staunchly democratic his fellow countrymen truly were. Consequently, there can be no simple answer to the question of his relation with the Jewish community, and of the effect this relation had on his politics as federal chancellor. Most importantly, there cannot be an answer that leaves out his attitude to the Jewish community during the years of his ‘first career’ as a local politician[7] in Cologne.

Not without reason, and certainly not primarily through calculation, Konrad Adenauer revisited his own experiences – especially those of the Weimar Republic years – during his encounters with David Ben-Gurion, and also with innumerable other representatives of Israel or of Jewish organisations. Among the Jews all over the world, too, respect for Konrad Adenauer is fed not least by his rejection of Nazi ideology, never doubted in the post-war years, not even by bitter opponents of his ‘policy of reconciliation’, and by the sympathetic attitude to Judaism and Jewish life in Germany he openly displayed on many occasions.

Towards the end of the 1920s the Nazis first began their embittered campaign of character assassination against the Zentrum (Catholic Centre Party) politician from Cologne. During the charged polarisation of the final phase of the Weimar Republic, he increasingly became the ‘great hate figure of all the radicals in Cologne’[8], as Hans-Peter Schwarz, Adenauer’s biographer, put it. At the centre of Nazi agitation against him was not only the specially ‘reheated’ accusation that Adenauer was a ‘separatist’[9] and supported the secession of the Rhineland from the German Reich, an accusation refuted without exception by all his biographers, but very soon also his positive attitude to the Jewish community, which he had never hidden.

Even before his appointment as Lord Mayor of Cologne, and until the day of his dismissal, Adenauer had always been in close contact with representatives of the Jewish communities but also with Jews in all walks of life: in academia, in the economy, and in the cultural sector. Some were particularly prominent and became defining companions for the talented local politician, informing his career.

A special relationship linked him to one of the most dazzling personalities of Jewish descent in Cologne during the days of the Weimar Republic, the banker Louis Hagen, a convert to Catholicism and heir and chairman of the board of the bank A. Levy & Co. Hagen was one of the most important industrial financiers of the Rhineland – indeed, of the entire Weimar Republic – by far. From 1924 onwards he was co-owner of Deutsche Bank and from 1915 until his death in 1932 president of the Chamber of Commerce in Cologne. Konrad Adenauer was, according to Hans-Peter Schwarz, among those indebted to Louis Hagen, as the latter had supported the career of the political ‘rising star’ without humiliating him.

Louis Hagen played a decisive part in Konrad Adenauer’s rise to the position as Lord Mayor of Cologne. It was Hagen who played the part of ‘kingmaker’ and determinedly supported the young local politician with the Liberals, the faction of the city’s parliament of which he was a member. Together with another influential Jewish politician of the Liberal faction, Bernhard Falk, who also respected Adenauer greatly and was on friendly terms with him, he succeeded in dispelling reservations held by the Liberal faction against the Zentrum party in general and, by extension, against Konrad Adenauer as well.

‘The years that followed’, Hans-Peter Schwarz writes about the friendship with Louis Hagen, ‘are characterised by a close alliance between the older and the younger man. They might be at loggerheads on occasion, but the two respect and appreciate one another.’[10] Konrad Adenauer certainly was a welcome and frequent guest at the entrepreneur’s ‘country house’ Schloss Birlinghoven near Bonn. Soon after taking office, Konrad Adenauer signed the guest book of the manor house as newly elected Lord Mayor. In 1919, Louis Hagen, who had already converted to Catholicism in 1886, even became Adenauer’s fellow party member: He left the Liberal faction in order to join the Zentrum faction of the city’s assembly of deputies.

Just how closely connected Konrad Adenauer felt to the banker became clear once more after the latter’s death in 1932. On 30 September, the president of the Chamber of Commerce had the honour of inaugurating the new Chamber of Commerce and Cologne stock exchange. On the evening of this eventful day, he suffered a stroke and died on 1 October. It was his friend Konrad Adenauer who gave the eulogy in his honour on 4 October.

Louis Hagen’s successor as president of the Chamber was another of Adenauer’s close companions, his friend Paul Silverberg. With Hagen and Falk, he made up the trio of men of Jewish descent who esteemed, encouraged, and supported Adenauer.

Paul Silverberg came from a traditional Jewish family but converted to the Protestant faith in 1895. A lawyer, he probably first met Adenauer during their years as trainee lawyers but certainly no later than 1903 when they were both lawyers and colleagues at the Higher Regional Court in Cologne.

Silverberg, who joined his father’s mining company, played a crucial part in the foundation of the mining giant RAG, which exists to this day and was the firm’s chairman for a long time. He earned himself the reputation of being the ‘lord of lignite’.[11] In fact, he was not only the leading figure of the Rhenish lignite district but also one of the most influential entrepreneurs of the Weimar Republic in general. He was involved in the reorganisation of the Stinnes Group as well as that of Hapag and Lloyd. He was an adviser to the Reichsbahn (national railways) as well as Deutsche Bank.

Politics, too, relied on his advice. Besides Konrad Adenauer, who was in close contact with him, this included above all the Reich Chancellor Heinrich Brüning, who even intended to appoint him minister for traffic and transport in 1931, but failed in this endeavour as a result of Silverberg’s ambitious conditions.

In the Weimar Republic’s declining years, Paul Silverberg moved closer to the right wing of the political spectrum. He made a financial donation to the Nazi party NSDAP via Gregor Strasser, with the aim of encouraging the party to be more pro-business. However, Paul Silverberg was never among the numerous advocates of having the Nazis participate in government during the time before the transfer of power to Hitler, a fact that clearly contradicts the stereotype nurtured above all within left- as well as right-wing circles to this day depicting Silverman as a ‘Jewish supporter’ and follower of Adolf Hitler.

It was probably towards the end of 1933, but at the very latest in early 1934, that Silverberg emigrated to Lugano in Switzerland. In 1936, he became a citizen of the principality of Liechtenstein, where he survived the war. Konrad Adenauer’s association with Paul Silverberg was so close that after the war he urged him to return to lead RAG once again. Silverberg declined but was awarded many honours by his home city of Cologne. On the occasion of his 75th birthday in 1951, he was appointed honorary president of the Cologne Chamber of Industry and Commerce as well as the Federation of German Industries. He remained in close contact with Konrad Adenauer in the post-war years, documented in their extensive correspondence.[12]

Of particular significance, however, was Konrad Adenauer’s cordial relationship with Dannie N. Heineman, demonstrated by their many personal encounters as well as the intensive correspondence between the two men which discussed – especially during the Third Reich – the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Gwendolin Goldbloom |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik |

| Schlagworte | 2024 • David Ben-Gurion • deutsch-israelische Beziehung • Deutschland • Diplomatie • Doppelbiographie • eBooks • englische Bücher • Freundschaft • Geschichte • Israel • Konrad Adenauer • Lebenswege • Neuerscheinung • Parallelgeschichte • Politische Macht • staatslenker |

| ISBN-10 | 3-641-32817-9 / 3641328179 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-641-32817-7 / 9783641328177 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich