1

Inspiration

Kyudo, perhaps more than any other martial art, is considered to be an excellent spiritual discipline when practiced under the tutelage of an inspirational teacher. It would be hard to imagine a teacher more inspirational than Onuma Sensei. He repeatedly told us that if we practiced diligently and made a real effort, kyudo could help us change our lives for the better. We once asked him if the practice of kyudo could also help rid the world of evil, or at least change it for the better. As silly and naive as our question must have sounded, he did take the time to answer that great philosophers have tried, for thousands of years, to address the question of good and evil, and that human beings have been trying to change the world from the first day of their existence—and yet humanity still struggles with the same questions.

Many people, deep down, are waiting for someone else to take charge of their lives and hand over a prescription for what to do or say in a given situation. Onuma Sensei always stressed that his intention was simply to teach us kyudo, not to teach us how to change the world. He also made it quite clear that neither was he trying to change us, adding that no one has the power to effect real change in others.

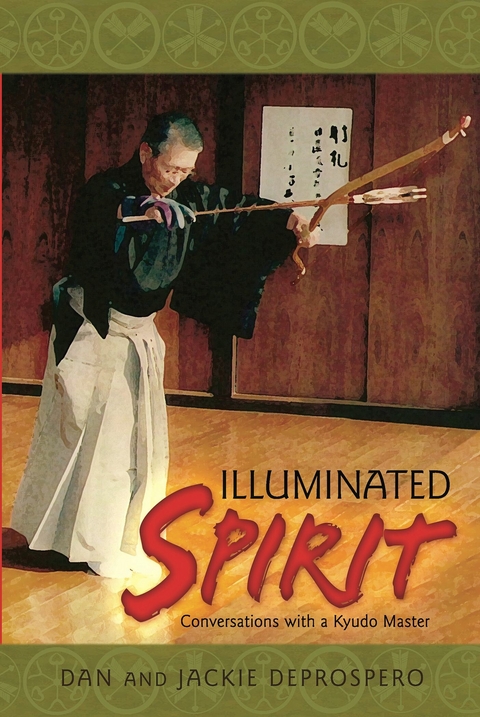

Onuma Hideharu, headmaster of the centuries-old

Heki-ryu Sekka-ha school of archery, in meditation

For Onuma Sensei, kyudo was a means of observing, understanding and changing his own life. He worked only on himself, believing that each of us is totally and completely responsible for improving his own character. Sensei had faith that if every human being were to approach life this way, the result would be smoother relationships, a more caring society and, ultimately, a better world to live in.

Can it really be so simple? The cynic will say that Onuma Sensei sounds like a man who would have students isolate themselves from other people’s problems in order to better themselves. But this is far from what he meant, as can be seen in one of his favorite analogies, of two people climbing a mountain:

The mountain looms equally high before us all. And the goal and the struggle we face is the same. The only difference between us lies in the fact that I started climbing long before you. Now when you look ahead you see me in a place where you, too, would like to be. If I allow myself to look back then I can see that in comparison with you I have came a long way. But I don’t like to look back because that hinders my own progress. Just like you, I’m always looking ahead toward the top of the mountain. But this doesn’t mean that I ignore others as I climb. I must always be ready to help those who follow. There is a great difference between looking back to compare yourself with the progress of others and looking back to guide others as they climb.

The point he is making is that one should follow a virtuous path simply because it is a good and proper thing to do, not from any expectation of compensation, glory or praise for our efforts. The reward lies in the act itself, and in the knowledge that having traveled that path we can then act as a guide to the others who will surely follow.

The Pursuit of Goals

Some years ago a fellow student questioned Onuma Sensei’s use of the English word “goal” during a teaching session. The student said that the use of this word implied a desire for some form of recognition, and asked if such a desire wouldn’t be a negative element that would interfere with one’s search for the truth. Obviously he had ignored the fact that Onuma Sensei was not a native speaker of English and had no doubt picked the word for its familiarity: originally a loan word, “goal” has now made its way into everyday Japanese. In any case, we decided to follow up on this line of thought in a subsequent conversation. Onuma Sensei said that his precise choice of words was irrelevant: that his purpose was simply to encourage us to aspire to the ultimate in human possibility. He never defined those possibilities for us, saying only that we must strive to attain perfection. In the next breath, however, he hinted that it is not humanly possible to achieve that goal, saying that the reward comes not from the attainment of perfection but from its unending pursuit.

Onuma Sensei (right) as a younger man, performing

Ogasawara-ryu ceremonial archery

That short exchange had a profound effect on both of us. Until then we had practically worried ourselves sick trying to advance from one stage of training to the next. We knew that our time in Japan was limited, and were determined to reach the goals we had set for ourselves when we first began. But Onuma Sensei made us see that we were focusing on the end rather than the journey, and that the end did not exist without the journey. From then on our training became richer and more fulfilling. Before too long we began to consider how often we focus on goals in other areas too, and we now make conscious efforts to spend what precious time we have on this earth concentrating on life’s journey rather than worrying about the end.

The Essence of Things

Onuma Sensei always stressed that in order to improve at anything we need to practice diligently, but that practice alone was not enough. We must also be inspired and hold onto our ideals, because without them our practice is weak and shallow. To truly understand a thing we must search for its essence. Skill, though important, only leaves us with a taste of the truth of a thing. When we watch someone who is technically skilled, but who lacks understanding of the essence of his own actions, we get the feeling that something is missing. The actions may be correct and the movements precise, but we are left unmoved by the performance. It is as if all meaning and purpose had been ignored in favor of technical expertise. The performance is devoid of the thing most crucial to its success: essence.

To Onuma Sensei that essence is a product of the human spirit that lies deep within us all. When we tap into the human spirit and bring its power to the fore, it serves as a foundation upon which to build technical skills, adding depth and feeling to the performance. Often the spirit lies dormant, numbed by modern life. But the spirit can be coaxed to the surface in a variety of ways. One method, controlled breathing, is used extensively in a number of disciplines and will be discussed at length below. Another method is controlled movement. Onuma Sensei was unequaled in his ability to move with such grace, dignity and strength of spirit that his entry into a room full of people invariably drew the attention of everyone present. He insisted that before one could learn kyudo one must first learn to do simple standing, sitting and walking exercises. More importantly, he stressed that the discipline and concentration needed to perform these exercises correctly would ultimately reward one with a heightened sense of confidence, stability and self-awareness that would enter into every aspect of one’s daily life.

The exercises shown here are derived from the practice of kyudo. They have little or no relevance to the way one moves while actually going about a normal routine, but this is precisely why they work. Since they substantially differ from more usual ways of moving they require a good deal more effort and concentration and are less apt to be performed mechanically. To practice the exercises one should feel that every action is connected to the rhythm of one’s breathing, for breath and spirit are one and the same. As you start a motion, breathe in slowly and steadily, controlling the flow of breath without straining. Then, as you finish, exhale in the same way. At all times both breath and movement should be measured, yet fluid.

Start from a kneeling position and, keeping the upper body straight, rise slowly and smoothly. Onuma Sensei taught that the body should rise as smoke rises. Meanwhile, slide the left foot forward, keeping it flat against the floor. As you complete the move, slide the right foot forward until it is even with the left foot. Do not permit the body to rock to either side or to shift up and down as you stand.

Onuma Sensei demonstrates the proper way to stand

When you walk, think of moving not from the feet but from the center of the hips, while letting the legs glide underneath the upper body. Do not stiffen the legs but do not let them bend excessively as you move. At all times the upper body should be held straight and should not be allowed to move from side to side. Move by sliding the feet across the floor in smooth, even steps. To turn to the right, slide the right foot straight ahead, so that the toes extend to about the center of the left foot, then turn both the right foot and the upper body, at the same time, ninety degrees. Let the right foot slide forward slightly. Then turn the left foot ninety degrees and slide it ahead of the right foot, to continue the walking sequence. Walk in straight line or, if space permits, walk and turn at right angles until you arrive back at your starting point.

To sit, reverse the footwork of the standing sequence, sinking slowly into position. Slide the right knee along the floor until it is even with the left knee, as you lower the body into the final kneeling position.

Pause for a moment in a seated position, then repeat the entire sequence of standing, walking and sitting. Practice the exercises repeatedly, but...