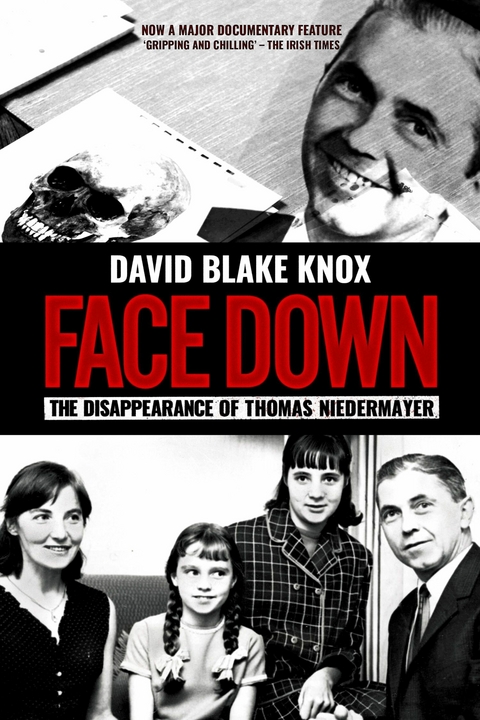

Face Down (eBook)

392 Seiten

New Island Books (Verlag)

978-1-84840-735-0 (ISBN)

DAVID BLAKE KNOX was educated in Ireland and at Cambridge University in England. He has worked as a TV Producer for RTÉ in Dublin, the BBC in London and HBO in New York. While in RTÉ, he devised and produced the innovative Nighthawks TV series, and was Director of TV Production. He established Blueprint Pictures, an independent TV and Film production company, in 2002. Blueprint specializes in Arts and Entertainment programming.

DAVID BLAKE KNOX was educated in Ireland and at Cambridge University in England. He has worked as a TV Producer for RTÉ in Dublin, the BBC in London and HBO in New York. While in RTÉ, he devised and produced the innovative Nighthawks TV series, and was Director of TV Production. He established Blueprint Pictures, an independent TV and Film production company, in 2002. Blueprint specializes in Arts and Entertainment programming.

2.

The Victim

The body had a name, a history and a life: Thomas Niedermayer was a German businessman. He and his family had been living in Northern Ireland since 1961, but he was born in 1928 in Bamberg, a small Bavarian town on the River Regnitz in Upper Franconia in south-western Germany. A large part of this medieval town is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, but Bamberg also has a darker side to its more recent history.

The town was the location of an important conference convened by Adolf Hitler in 1926. He had become concerned that the Nazi Party was about to split into two regional factions. One of these consisted of Gauleiters (District Leaders) from northern Germany, who were generally regarded as more urban, more radical and more sympathetic to socialist ideas. The others were Gauleiters who came from more conservative rural areas in southern Germany and who were less interested in abstract theory than in nationalist and racist ideology.

Hitler wanted the issue to be resolved as clearly as possible and the fact that he chose to hold this conference in a small southern town like Bamberg indicated where his own preferences lay. The Bamberg Conference proved decisive in determining the future development of the Nazi Party and in establishing the dominance of its conservative faction. However, in some respects, the final act of the conference in Bamberg did not take place until eight years later. That was during the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ when scores of members of the Nazis’ radical faction were murdered by the SS on Hitler’s orders.

Thomas Niedermayer was born two years after the Bamberg Conference and he was 4 years old in 1933 when Hitler and the Nazi Party took control of the German state. Like other fascistic or extreme populist parties, the Nazis claimed to represent a movement of youth – and ‘fresh blood’ – that was somehow destined to supplant the older generations and correct their grievous mistakes. In that context, Hitler believed that the indoctrination of children – and male children, in particular – with Nazi ideology was essential for the future of his ‘thousand-year Reich’. He wanted to produce boys that were ‘as tough as leather and solid as steel’. The Hitler-Jugend (Hitler Youth) programme was designed to create future generations of such loyal and dedicated Nazis. It was established in 1925 and by 1930 had enrolled almost 25,000 members. When Hitler came to power in 1933, all other youth organisations in Germany were compelled to disband and become part of the Hitler-Jugend. By the end of 1933, its membership had reached almost 2 million.

As the 1930s progressed and Nazi control of Germany tightened, it became increasingly difficult for children to avoid membership of the Nazis’ youth movement. By the end of the decade, there were almost 8 million members of the Hitler-Jugend. When Thomas Niedermayer was 7 years old, the Reichstag had passed the Gesetz über die Hitler-Jugend: a law which made it mandatory for all male German children who were aged 14, free of physical or mental disabilities and of proven ‘Aryan’ descent to become members of the Nazi Youth organisation. Thomas turned 14 in 1942.

In some respects, Thomas Niedermayer was fortunate in his date of birth. In the closing years of the Second World War, large numbers of boys in the Hitler-Jugend were drafted and trained to fight as infantry troops in support of the regular army. Wehrertüchtigungslager (Defence Strengthening Camps) were set up throughout Germany and boys were taught how to use modern weaponry. In the final stages of the war, the Nazis even recruited an entire SS Panzer Tank Division from the Hitler-Jugend. These child-soldiers proved ready to die for their Führer and the 12th Panzer Division suffered 60 per cent casualties following the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944.

In 1942, however, members of the Nazi youth movement had not yet been assigned to military service. Instead, they were sent to work in war-related industries. So many men had been drafted into the Wehrmacht (the German Army) that there was a chronic shortage of labour in Germany. This shortfall had been met, in part, by the introduction of German women into occupations previously reserved for men, and the use of vast numbers of slave labourers from countries invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany. However, even that was not enough to feed the ravenous appetite of the German war machine, and young boys who were members of the Hitler-Jugend were also recruited. Some, like Thomas, were specifically assigned to work for the Luftwaffe (the German air force). He concluded his formal education in school at the age of 14 and was sent to be trained as an aircraft mechanic in Friedrichshafen where the Zeppelin and Dornier plane factories were based. From there, he was taken to work in a Luftwaffe plant in Karlsruhe on the French-German border.

This assignment may have helped to ensure that Thomas Niedermayer survived the war, but it does not mean that he escaped unscathed. In the 1930s, the Nazis had established Karlsruhe as an important training base for Luftwaffe pilots and so it was an obvious location for aircraft factories. During the early years of the war, Karlsruhe had managed to escape relatively undamaged in comparison with some other German towns and cities. Air raids did take place, but they were infrequent and spread over a period of time. This allowed Karlsruhe’s inhabitants to prepare effective forms of defence such as the construction of underground civilian shelters and the digging of large water pits to assist firefighting. Reproductions of Karlsruhe’s aircraft factories were built in nearby forests, and these were bombed repeatedly by the RAF before advances in radar technology revealed them to be fakes.

By 1942, however, the Allies had identified the factories where Thomas worked as being of strategic importance to the Luftwaffe, and RAF Bomber Command had listed Karlsruhe as one of the top 25 German cities that they wanted to destroy. The Allies’ stated objective was not only to attack the city’s aircraft factories, but also ‘to break the morale of the civilian population’. In the middle of 1943 – soon after Thomas Niedermayer had arrived in Karlsruhe – Allied bombing raids on the city began to increase in number, in efficiency and in ferocity. In the early morning of 27 September 1944, the RAF launched a major raid on the city. A formation of 248 bombers dropped over 200,000 incendiary devices as well as hundreds of tons of high explosives. A tsunami of fire swept through Karlsruhe’s eastern districts. However, the cold, wet weather and the determined efforts of the city’s fire fighters managed to limit the damage. Ironically, this meant that Air Marshal Arthur Harris, of RAF Bomber Command, ordered further massive assaults on Karlsruhe in order to ensure its complete destruction. On 4 December 1944, the city was attacked by 513 RAF planes, which carpet-bombed the city – dropping huge numbers of heavy aerial mines, explosive bombs and incendiary devices. There were more massive air raids later that month – one involving almost 1,000 planes – and large tracts of the city centre were completely obliterated. In the closing years of the war, everyone in Karlsruhe lived under constant threat of sudden death. By the beginning of 1945, hundreds of the city’s inhabitants had been killed in the bombings as well as hundreds of slave workers. Less than 4,000 family homes – out of 17,000 – were left standing.

By all accounts, the final months of the Second World War generated widespread fear and panic among the city’s inhabitants. According to witnesses, the cacophony of roaring aircraft engines, howling sirens, exploding bombs and defensive gunfire was incessant and terrifying. Much of Karlsruhe’s population spent the final weeks of the war hiding in dark and dank underground shelters. They could hear French tanks and infantry troops advancing closer to their city. It seemed that nowhere was safe: even carts in the fields and individuals walking home were strafed by low-flying Allied planes.

In the last weeks of the war, German military engineers blew up a number of bridges to prevent Allied troops crossing the Rhine and the road entrances to Karlsruhe were also barricaded. But, on the morning of 4 April 1945, after a heavy artillery bombardment, French forces began to enter the city. It seems that the only armed resistance that the French encountered in Karlsruhe came from some small units of the Hitler-Jugend. These were subdued within a matter of hours and the French had taken complete control of the town by eleven o’clock of that spring morning.

All males in the city who were between the ages of 16 and 45 were required to report to the French military authorities to be examined and questioned. Around 300 adult men were sent to an internment camp in nearby Offenburg, but 700 or so were held as prisoners in Karlsruhe. These prisoners included many former members of the Nazis’ youth movement, one of whom was Thomas Niedermayer. The Allies’ plan was to re-educate these young people and try to counteract their years of indoctrination by the Nazis. This usually involved compelling them to watch graphic footage of the atrocities that had taken place in camps such as Belsen and Treblinka.

As part of this re-education, in Bavaria, former members of the Hitler-Jugend were taken to visit the concentration camp at Dachau, where many thousands had died as a result of starvation, neglect, brutality and illness – as well as in hideous medical experiments when prisoners were frozen alive and subjected to violent decompression. Soon after the war ended, part of the camp at Dachau was used to house ethnic German refugees from...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.10.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | arte • BBC • Biography • David Blake Knox • Documentary Film • Dolours Price • family tragedy • Ingeborg Niedermayer • Northern Ireland • Peace and Reconciliation • rte • The Troubles • Thomas Niedermayer |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84840-735-1 / 1848407351 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84840-735-0 / 9781848407350 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich