Sleeping on Islands (eBook)

256 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-37531-8 (ISBN)

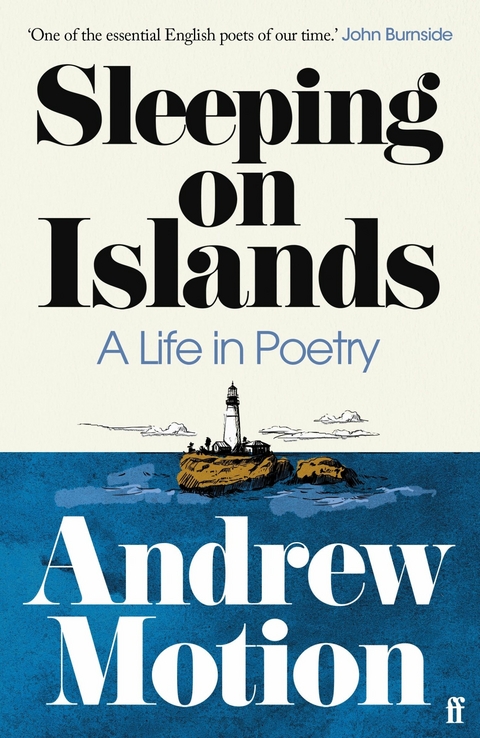

Andrew Motion was UK Poet Laureate from 1999 to 2009, is co-founder of the online Poetry Archive, and has written acclaimed biographies of Philip Larkin and John Keats among others. His memoir of childhood, In the Blood, was published in 2006, and its sequel, Sleeping on Islands: A Life in Poetry, appeared alongside Selected Poems: 1977 - 2022 in 2023. He is Homewood Professor in the Arts at Johns Hopkins University, and lives in Baltimore.

Andrew Motion has been close to the centres of British poetry for over fifty years. Sleeping on Islands is his clear-sighted and open-hearted account of this remarkable career. It takes us from scenes of a teenage home-life coloured by tragedy and silence - where writing was as much a refuge as an assertion - to the excruciations of early public appearances, to the decade he spent as Poet Laureate, promoting and ensuring the central place of poetry in a nation's character. Along the way, we hear about the risks and sacrifices involved, as well as the difficulties of sustaining a commitment to writing within a helix of other obligations. We see in close-up the significance of Motion's formative relationship with W. H. Auden and his subsequent friendship with Philip Larkin. And during his time as Laureate, we witness memorable encounters with Royalty and Prime Ministers, and discover the costs and complications that accompany such a high-profile role. By turns moving and humorous, this is the intimate story of a rare poetic life. And it proves Motion's contention that the poems we most enjoy 'are not weird visitations, or ornaments stuck on the surface of life, but part of life's daily bread'.

Andrew Motion was UK Poet Laureate from 1999 to 2009 and is co-founder of the online Poetry Archive. In 2015 he was appointed Homewood Professor in the Arts at Johns Hopkins University; he lives in Baltimore.

A pattern was beginning to appear, like the beginning of a story. But to call it a story felt wrong. How could there be a story, when there was no reliable way of connecting one thing with the next? Life was random, wasn’t it, a series of accidents? I wasn’t sure. One minute it seemed so, and the next it felt as though an idea of structure emerged from events, or imposed itself on them, whether I liked it or not. Take poetry, for instance. I’d begun writing because it was a place to be private, because it helped me to deepen what I was feeling (and sometimes to understand myself better), and because it was about as unlike my father’s world as anything I could imagine. Then my English teacher read what I’d done and encouraged me to keep going. Then I began reading more seriously and got my crush on Rupert Brooke – which led to Skyros, which led to Geoffrey, which led to yet more encouragement, which had now brought me to the point of leaving home for university, where no one in my father’s family had been before. That all created a sort of pattern, didn’t it? That sounded like the beginning of a story?

As a child I’d thought time must be like a broken mirror, because I could see my face – my idea of myself – flashing back at me from this piece or that piece of life, but otherwise disappearing in the cracks between each fragment. Now the pieces seemed to be better connected than I’d imagined, but I still felt that I was looking at reflections, never seeing the whole picture, never living inside the mirror. Was this something I’d inherited, or was it just me? There was no point asking my father, he’d only harrumph – it was too personal. And I couldn’t ask my mother because she was still floating in her unconsciousness, not speaking. Which meant there was all the more reason for me to hurry up and leave home, and meet the sort of people who were supposed to be interested in questions like this.

Before that happened, I had another idea about stories. About my mother’s story, in particular. When I thought of her life purely in terms of events, it contained not much before the accident: a quiet childhood in Beaconsfield as the daughter of a GP; a dim school and no chance of university (because she was a girl); a quick trip to South Africa to ‘see the world’; a part-time job working as a typist in Pinewood Studios; then marriage to my father when she was twenty-three, two boys in quick succession, and a housebound life as a housewife, punctuated by illnesses of one kind and another. All insignificant in the great scheme of things, but all precious and fascinating to me because they were the facts of her life. Because they were her story.

Then came the accident, which looked at from one angle marked the end of her story but was really the beginning of another. Although this second story was different. It was a collection of moments in which time never moved to a steady beat with a steady step, but lurched, veered, stopped, started again, wandered. So who was to say what constituted a story and what didn’t, and who was to decide on the true scale and importance of things? Did education, travel, love, and family matter more than shock, pain, disappointment, and grief? Or did I have to think differently about what had meaning in life and what didn’t? Either everything was a story, or nothing was: it all depended on how I looked at the world. And on whether I trusted facts – because facts could be fickle, as my mother also proved.

In the days immediately after her accident, my father and Kit and I had scrambled to find out what exactly had brought it about – but because no one had seen her fall, there were no completely reliable witnesses. The consensus was, she’d been riding her pony Serenade through a wood, the pony had stumbled as she came out into a field, she’d flopped forward but clung on to the pommel of the saddle, the rotation of the pony’s shoulder-bone had knocked off her hard hat, and when she eventually let go of the saddle she landed on a cement track; the blow knocked her out, cracked her skull, and produced a blood clot on her brain which the doctors later removed; now she was in a coma.

It helped to know this sequence of events. We could imagine the scene, understand the connections between cause and effect, and gradually learned how to compress the story into a shape that made it repeatable. We found ways to live with it. But a while later, after I’d published an account of the accident somewhere, a man called Paul Smith wrote to me out of the blue saying that I’d got it wrong. My mother had been riding near a big house where he worked as a gamekeeper, and he’d seen it all. In the old days, there’d been a ha-ha dividing this house and its garden from the surrounding fields, and although this ha-ha had been filled in long ago, it had left a dip in the ground which was often lined with shadows. When Serenade had seen these shadows, she’d been spooked, reared up, and caught my mother off guard. My mother had tumbled backwards out of her saddle, and as she fell Serenade had instinctively kicked out, clipping my mother on the side of her head with the edge of her metal shoe. Smith said that he’d run forward and knelt down beside her in the grass, but she was out cold, with blood dribbling from her ear; he’d raised the alarm and waited with her while someone else rang for an ambulance, and half an hour later she was taken away to hospital.

If this story was true, and I believed it was, did it matter that I now had to revise the version I’d been living with? In one sense it made no difference to anything, because the outcome was still the same: my mother was in hospital and unconscious. But in other ways it changed everything – not just the details of the setting, but the associations and the forces those details suggested. A big house and its surroundings instead of a wild wood. Less risk and more simple bad luck. A tumble with someone watching instead of a fall in solitude. But what did these differences amount to? I didn’t know how to decide. Stories mattered and they didn’t matter. They seemed coherent, but really they were shadows flickering in the grass.

*

It crossed my mind that I might be reluctant to think of lives as stories, because the story I knew better than any other, which was the story of my mother’s present, was only going to end one way. In other words, the chain of events implied by the word ‘story’, which was also the organising principle in all the novels I’d read (admittedly not many), was bound to form a sequence that ended in death. Poems, on the other hand, which weren’t so keen on telling tales in a consecutive way, were a means of confirming but also of weakening that connection. They were a way of accepting the inevitable, but also of arresting time or stepping outside time.

This paradox felt valuable because it was like my experience of time itself. Which is to say: now that my childhood was ending – was already over, perhaps – parts of it were hardening into pictures that refused to fade. Sometimes these pictures troubled me because I thought they were equivalent to the songs of the Sirens and would lure me back to the past when it was the future I wanted. More often they seemed like visions: things that I had seen with my heart and not just my eyes – often very small-seeming, very modest, very humdrum things, but marvellous nonetheless. Spots of time. A glimpse of the scullery next to the kitchen in our old house, for instance, where years ago my mother had washed sheets in the sink on laundry day, then fed them through the mangle before scooping them up in a kind of hug and taking them outside to hang on the line by the greenhouse. Her hands were mottled with cold, and the wet ghost of the sheets made an impression on the front of her housecoat. After she’d gone out, the cracked wooden lips of the mangle grinned at me with their idiotic bubbles.

Or the coal man presenting his sooty face outside the kitchen window, touching his grimy cap to my mother and giving her a thumbs up. Then the coal man opening the flap of the cellar, heaving the sacks against his chest one by one, gripping them by the corners to empty them, and nearly but not quite disappearing as the coal-lumps rumbled downwards into the dark, leaving a wisp of slack that fled across the yard like a genie escaping its bottle.

Or the trampled mud near the cattle trough in the far corner of the field adjacent to the house, where the top one or two inches of water always froze solid in the winter, which meant the cows couldn’t drink from it. When I went to sort it out, waving away the drooling mouths and coils of steamy breath, I chipped round the edges of the ice because I wanted to take it out in a single sheet, like the glass for a window-frame, then hold it up to the sun. But even when I managed that, it was impossible to see through; there were too many bubbles and ridges. I ended up chucking the ice sheet down onto the mud and watching it smash, which made the cattle buck and snort and shimmy away, then cautiously come back for a closer look, still breathing hard through their shiny noses.

Or the knife-grinder who once every autumn parked his bike on the tarmac outside the front door, propping its wheels off the ground so that the bike stood still while he turned the pedals to spin the sharpening...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | Auden • diane athill • Philip Larkin • Seamus Heaney • Stet • Ted Hughes • The Queen |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-37531-6 / 0571375316 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-37531-8 / 9780571375318 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 381 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich