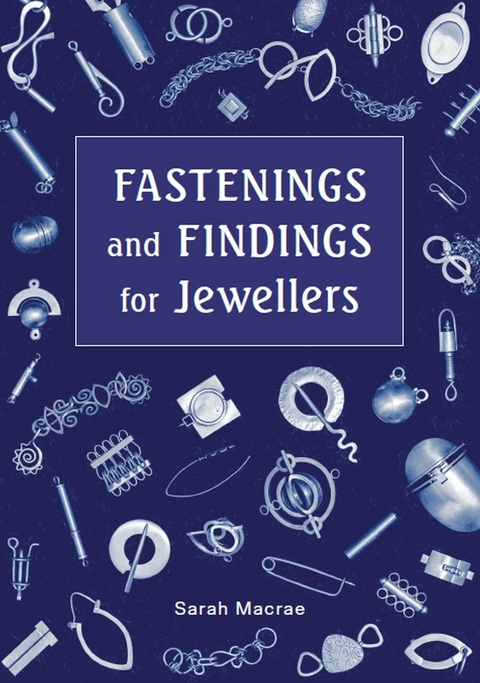

Fastenings and Findings for Jewellers (eBook)

112 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4123-1 (ISBN)

Sarah Macrae has been making and teaching jewellery for more than forty years, exhibiting nationally and internationally with the Association for Contemporary Jewellery, Designer Jewellers Group, and at Goldsmiths Hall. For the last twenty-five years she has taught short courses at West Dean College. She works mainly to commission.

Fastenings and Findings for Jewellers is an essential guide to making a functional part of a piece of jewellery into a graceful, integral feature. Complete with step-by-step instructions, it explains the requirements of design, and emphasizes the importance of safely and securely fastening the piece. Having explained the principles of various catches, it then looks at how the fastening can be adapted to suit a particular design. With tips and advice throughout, this practical book provides creative solutions to a practical necessity and thereby adds inspiration to a design.

CHAPTER TWO

BROOCHES

The brooch has served both a practical and decorative function since earliest times; it has been more prevalent in northern Europe, perhaps where lower temperatures meant more clothing to fasten to keep warm. Between the Neolithic straight pins and the invention of buttons in the Middle Ages, the fibula was an early form of the safety pin and was used to fasten clothes. Fibulae were made from one continuous piece of metal (or sometimes two) in bronze, iron, silver and gold; worn by everyone, they range from simple functional pins to highly decorative designs. The bow brooch was a more elaborate form of fibula with a high arched design, perhaps to gather in more fabric and which often incorporated a horizontal spring. Circle brooches where the pin rests on the front of the brooch were sometimes inscribed with messages and given as love tokens. Annular brooches had longer pins that pushed through the fabric behind the circle and were probably held in place with a cord or thong. One of the most famous of the annular brooches is the ‘Tara’ brooch, an amazing example of decorative metalwork on display in the Dublin Museum. The Tara brooch has a woven metal chain attached to one side, possibly proving the theory of the way they were fixed to the wearer. Where other annular brooches probably used leather thongs that have perished, on some examples there is evidence of small fixings for a thong. Penannular brooches were made both before and after the period of annular brooches (penannular means ‘broken circle’) and although they are mostly thought of as being Celtic and there are some very large examples in the British museum, the penannular mechanism is seen in other cultures too. They vary from tiny delicate Indian examples to massive North African brooches. For the Celtic brooches the decorative focus is the circle, or for some it’s the terminals at the break in the circle. In North African jewellery the focus is a decorative or symbolic element at the head of the pin with a very simple circle to turn and lock it into place. Double penannular brooches joined by a chain were and still are worn in some cultures indicating marriage and when widowed the chain is removed. In more recent history the fastening has been hidden behind the piece as brooches became purely a decorative feature and the functional aspect of fastening clothing disappeared. In contemporary jewellery the fastening has often become a feature of the brooch again with the function of the piece being integral to the design.

Set of four penannular brooches in an ebony box frame. The circle of the penannular form has more emphasis with a small decorative feature on the head of the pin. Silver, alabaster, acrylic, ebony, 18ct gold detail and blue topaz bullet point terminals. Sarah Macrae, 2000.

Hollow form silver penannular with 18ct gold detail and a blue topaz bullet point terminal. (Photo: Joel Degan)

Brooch pins vary in thickness depending on what kind of fabric the brooch is intended to be worn on. A brooch worn on a heavy weave or knitted fabric can have a thick silver pin without damaging the fabric. If the brooch is more delicate and it is going to be worn on a finer weave cloth, there is a limit to how fine a silver pin can be before it becomes too weak. A pin made from nickel or 9ct can be finer and stronger. Piano wire (sprung steel) or a sewing needle with the eye pushed into a short length of tube can also be a good solution.

Fibula – the original safety pin

Material:

100mm of 1.2mm wire

•With round-nosed pliers, make a small curl or hook at one end of the wire.

•Holding the wire with pliers, bend the wire with your fingers at right angles.

•About 35mm along the wire, hold the wire with round-nosed pliers and wind the wire around at least twice to make a spring, finishing with the wire pointing in the direction of the hook.

•Harden the wire through polishing or burnishing, making the resting position of the pin pointing up above the hook so it has to be pushed down under tension to catch under the hook.

A very simple fibula, the original safety pin, 40mm × 10mm.

Simple fibula made from a continuous length, 80mm × 40mm.

Reproduction of a Roman zoomorphic brooch made for a workshop at the Novium Museum in Chichester, 43mm × 30mm. It had to be made without soldering so the catch was adapted from the original Roman one so that it could be riveted in place. Bronze with verdigris patination.

Roman zoomorphic brooch catch

The Romans made these in vast numbers, and they tended to reflect the animals in the particular area where they were made. Because the Roman Empire at its height extended from northern Europe to north Africa there are brooches of everything from rabbits to lions. These are usually low relief castings in bronze and have a very simple catch. The catch described can be riveted or soldered onto the back of the brooch.

Materials:

A strip of 0.5mm sheet, 20mm × 35mm

100mm × 1.2mm wire

5mm × 1.5mm wire for the rivet

Roman style catch cut out of sheet copper (35mm × 20mm), drilled then riveted to the brooch.

1. Template for plate.

2. Folded to make fitting for pin and hook, side view with pin.

3. Top view with pin which was then riveted through the two folded up ‘ears’.

•Saw out the shape in the diagram.

•Drill 2 × 1.5mm holes centrally in the ‘ears’.

•Bend the ‘ears’ at right angles to the strip so the holes are parallel to each other.

•Bend the other end at right angles and, using round-nosed pliers, form a hook.

Roman pin.

1. Wind the wire tightly at least twice, and then slide off rod (1).

2. Slide back on the rod the opposite way and curve the longer length of the wire (2).

3. Wind the wire the opposite way, slide the second winding off the mandrel, and with another piece of the same diameter steel to support the twist and give some leverage, reverse the direction of the winding (3).

4. Showing after the winding has been reversed.

5. From the other side (4).

•Use an old 1.5mm drill fixed the wrong way in a vice. Take the 1.2mm wire and starting 50mm along the wire, wind it tightly around the drill bit (away from you) twice, leaving the two ends of the wire pointing in the same direction. (1)

•Take the coil off the drill bit and replace the other way round, so the longer end is on the left. (2)

•Form a curve with the longer length now on the left, pass under the drill bit and leaving a small gap wind the wire in the opposite direction. (3)

•Slide the second coil off the drill bit.

•Taking another 1.5 drill bit, slide it into the second coil and turn the second coil inward towards the first coil, the curve should be on the same side and the two free lengths should be coming from the middle. (4)

•Trim the excess wire from the longer length, leaving a small prong 5mm beyond the coil that will act as the spring off the back.

•Fit the coil into the U shape with the pin at the top.

•Push a tight fitting 1.5mm wire through the two holes in the U and the coil and rivet (see Chapter 1).

•With a pair of round nosed pliers bend the small 5mm section of the wire so the end of the wire is in contact with the back of the brooch.

•The pin should be at an angle about 30 degrees to the back.

•Snip the end of the pin so it finishes just at the end of the hook.

•Burnish the pin on a steel block to harden it, turning and slipping off the end to form a bullet-point end.

A double-sprung pin based on arched Roman bow brooches

Materials:

60mm × 15mm × 0.8mm thick sheet

5mm × 3mm tubing

25mm × 2mm wire

160mm × 1.2mm wire (start with extra and cut to length at the end)

These were named by archaeologists due to their shape having a visual similarity to a crossbow and were usually cast from a solid piece and then the pin and spring were added as a single length of wire. This is my interpretation of the form using the principle of the sprung pin rather than attempting to reproduce one. A tapered rectangular shape about 50mm × 15mm at the widest point from sheet 0.8mm thick with a 10mm tongue 5mm wide which soldered to the short length of tube will become part of the spring hinge and two shorter tags either side of the other end that will form the double hook.

Roman bow brooch bronze, 45mm × 16mm. (Author’s collection)

1. Three silver roller printed bow brooches with double pins (50mm × 22mm, 50mm × 27mm, 50mm × 23mm).

2. The reverse of three silver roller printed bow brooches with double pins using the long curve to give tension to the pins so they spring...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.10.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Design / Innenarchitektur / Mode | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | annular brooch • bail • bangle • Box • Bracelet • Brooch • Catch • Celtic • Chain • cufflinks • ear climber • earring • Enamel • fishu joint • Hook • hook and eye • Magnetic • necklace • penannular brooch • pendant • PIN • Reuleaux triangle • Ring • riveting • Romans • Screw thread • Silver • spring catch • Wire |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4123-2 / 0719841232 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4123-1 / 9780719841231 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich