Peak Performance Table Tennis (eBook)

470 Seiten

Meyer & Meyer (Verlag)

978-1-78255-510-0 (ISBN)

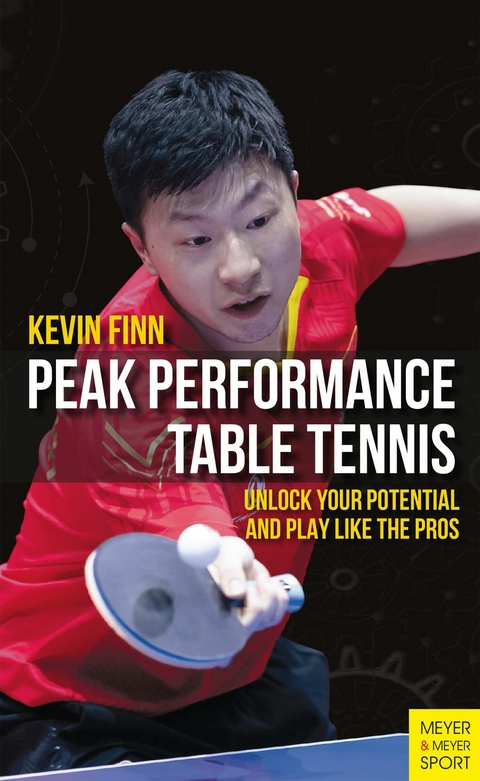

Kevin Finn is a strength and conditioning specialist, a certified speed and agility coach (CSAC), and the owner and creator of Peak Performance Table Tennis. As a strength training and nutritional consultant with a master's degree in education, he specializes in breaking down complex information and arming people with the knowledge and tools necessary to transform their physiques and take their performances to the next level. As a table tennis player, he specializes in playing defensively, losing frequently, and spending inordinate amounts of time researching and tweaking his setup. He can be found frequenting the online table tennis forums under the moniker, Joo Se Kev.

Kevin Finn is a strength and conditioning specialist, a certified speed and agility coach (CSAC), and the owner and creator of Peak Performance Table Tennis. As a strength training and nutritional consultant with a master's degree in education, he specializes in breaking down complex information and arming people with the knowledge and tools necessary to transform their physiques and take their performances to the next level. As a table tennis player, he specializes in playing defensively, losing frequently, and spending inordinate amounts of time researching and tweaking his setup. He can be found frequenting the online table tennis forums under the moniker, Joo Se Kev.

TAPPING INTO THE MATRIX: IMPROVE YOUR TABLE TENNIS WITH RAPID LEARNING

“Be stubborn about your goals and flexible about your methods.”

—Unknown

Remember that scene from The Matrix where Neo is hooked up to a computer and they upload black-belt level mastery of dozens of martial arts disciplines directly into his brain? In minutes, he was able to learn what would have taken many lifetimes to learn in the real world. Imagine if you could do the same for table tennis…

Jan-Ove Waldner’s ball control and artistry, Ryu Seung-min’s footwork, Wang Liqin’s raw power, Xu Xin’s spin… I suppose you’d end up with a player who looks a lot like Ma Long. Perhaps that’s how he’s been so dominant? Someone check the footage to see if he has those Matrix-style “port holes” in the back of his head!

On a more serious note, ever since I saw that scene from The Matrix, I’ve always been fascinated with the concept of learning. Is it actually possible to “hack” the learning process? How do different methods of practice impact learning? In search of answers, I took a deep dive into the literature regarding motor learning and how it relates to optimizing sports performance. This chapter is a distillation of the most relevant and useful learning tactics I came come across—most of which can be neatly dropped right into your existing practice schedule. To set your expectations accurately, don’t expect anything revolutionary. This isn’t science fiction, and unlike The Matrix, there are no quick fixes that can substitute for good, old-fashioned hard work.

Instead, I will provide some suggestions to help you better utilize the time you already have so you can eke out a little more progress. I have intentionally chosen some strategies that seem relatively novel and counterintuitive because, in doing so, I hope to offer you some untrodden paths you may have never considered. Don’t feel like you need to try to implement everything from this chapter all at once; instead, pick a strategy or two and simply give them a try. If you notice a positive difference, great! If not, try another or simply go back to what you were doing.

FUN FACT:

Hugo Calderano, the first player from Latin America to reach the Top 10 of the ITTF World Rankings, likes to use a Rubik’s Cube to train himself to both think and move quickly at the same time. He can solve it in under 20 seconds!

WHAT DOES THE RESEARCH SAY REGARDING MOTOR LEARNING?

Motor learning is the process of acquiring and mastering simple and complex movement patterns through practice or experience. Although the data regarding motor learning is somewhat messy, I’ve done my best to make recommendations based on where I felt the weight of the evidence lies. I came across one integrative review by Nicholas Soderstrom and Robert Bjork titled “Learning Versus Performance: An Integrative Review” [1] that I found particularly enlightening and will be drawing from heavily in this chapter. It matches both my own reading of the literature as well as my personal experience teaching and coaching individuals over the past 10 years. Before diving into the review, we should first examine the terms performance and learning in the way they define them:

PERFORMANCE

“The temporary fluctuations in behavior or knowledge that can be observed and measured during or immediately after the acquisition process.”

In other words, how well can you execute the task right now?

Example:

After practicing your forehand push in a given session, you are able to execute the movement consistently and with good form at the session’s end. That reflects good performance.

LEARNING

“The relatively permanent changes in behavior or knowledge that support long-term retention and transfer.”

Example:

How well can you perform that same forehand push a couple of days later? The extent to which you can reproduce your previous performance reflects your learning.

The reason this distinction matters is that there is a counterintuitive relationship between these two terms, as Soderstrom and Bjork describe here:

The distinction between learning and performance is crucial because there now exists overwhelming empirical evidence showing that considerable learning can occur in the absence of any performance gains and, conversely, that substantial changes in performance often fail to translate into corresponding changes in learning. Perhaps even more compelling, certain experimental manipulations have been shown to confer opposite effects on learning and performance, such that the conditions that produce the most error during acquisition are often the very conditions that produce the most learning.

This means the practice protocol that produces the most substantial gains in performance within a session may not necessarily translate into the best performance gains long term. This distinction is useful on two fronts.

First, knowing this fact should bolster your resolve during a training session where many errors are being made. In this situation, it’s easy to feel like you’re not improving or are even regressing due to your poor performance. The studies outlined in this review, however, demonstrate that learning can occur even in the absence of performance. This should be a rallying cry for you in the thick of training and allow you to maintain a level of enthusiasm and clear-headedness that you may not have had otherwise. Secondly, it also opens the door to alternative methods of training that you might have otherwise discounted due to a high number of initial errors. So, with this in mind, let’s look at a few of the key concepts found within this review.

CONCEPT ONE: LATENT LEARNING, FATIGUE, AND OVERLEARNING

Imagine performing a basic drill where you’re working on your forehand loop against a block. As mental and physical fatigue sets in and you begin to make more mistakes, does continuing the drill beyond that point only serve to reinforce those mistakes? Should you terminate the drill as soon as your performance begins to decline in order to maintain “perfect practice”? Not necessarily. Soderstrom and Bjork identify three interacting concepts that explain how you may still be benefiting from practicing a drill, even though performance has stagnated or declined:

The learning versus performance distinction can be traced back decades when researchers of latent learning, overlearning, and fatigue demonstrated that longlasting learning could occur while training or acquisition performance provided no indication that learning was actually taking place.

For example, Soderstrom and Bjork cite one study [2] where trainees from the Air Force performed a rotary pursuit task where they manually tracked a target with a wand. The researchers manipulated the rest intervals between trials in a way that caused some of the trials to be performed in a fatigued state. Unsurprisingly, the subjects’ performance suffered on the individual trials performed while fatigued, but when they were retested (after fatigue had dissipated), their performance improved despite the earlier decline. So, learning can indeed occur even when short-term performance is masked by fatigue.

This doesn’t mean fatigue has no consequences on learning, however. There is research that shows motor learning occurs at a slower rate when the task is performed in a fatigued state [2a]. Furthermore, the negative effects seem to persist even in subsequent sessions when fatigue has dissipated. Thus, you should take steps to minimize fatigue as much as possible when learning (the “distribution of practice” method outlined in the next section is good for this), but at the same time, don’t lose hope and abandon training simply because you are making mistakes while learning. It’s a balancing act!

Soderstrom and Bjork also identify overlearning as a critical part of improving long-term retention of a skill. As a musician, this is a concept with which I am intimately familiar. If you plan on performing a piece in front of a group of people, it is not enough to simply practice until you can perform it with no errors. To reliably perform it well, you must practice until you can perform the piece perfectly, many times in a row under a variety of conditions. This is overlearning. It’s performing repetition after repetition even after mastery seems to have been achieved. This is the reason dedicating enough “table time” is so important to developing your skills as a table tennis player. You may be able to learn how to perform a forehand loop in relatively short order, but how reliably will you be able to implement that stroke within the context of a competitive match?

Learning...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.11.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Aachen |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sport ► Ballsport ► Tennis |

| Schlagworte | Advanced tactics • peak performance • Sports Nutrition • Sports Science • Supplementation • Table Tennis • training methodology • winning mentality |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78255-510-2 / 1782555102 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78255-510-0 / 9781782555100 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich