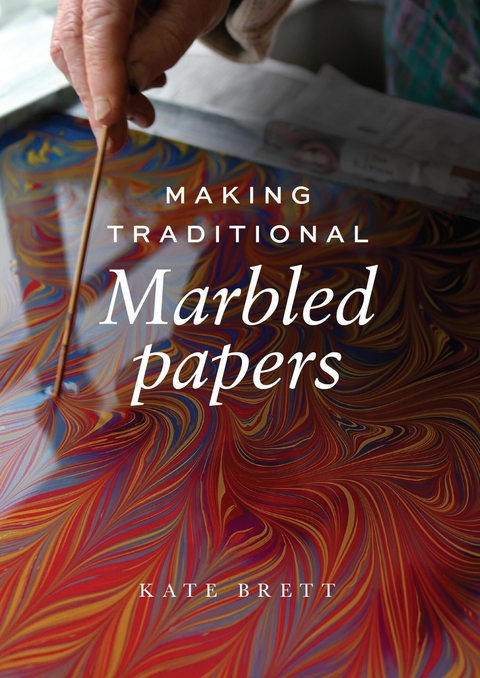

Making Traditional Marbled Papers (eBook)

112 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-1-78500-958-7 (ISBN)

Kate Brett is a paper marbler, specialising in traditional patterns and techniques from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. She has run her business Payhembury Marbled Papers for over forty years, and her papers are used by bookbinders, designers and makers worldwide.

INTRODUCTION

The thousand-year-old craft of marbling is alive and well, and it can be practised and appreciated by everyone, from children to professionals. There are various different methods of marbling, and it can be used in commercial trade, as the basis for artistic or academic study, or as a source of relaxation, therapy or fun.

Endpapers from early eighteenth-century books, showing the colours generally used in early marbling – Indigo, Red Lake, Yellow Ochre and Lamp Black.

The Placard – a very early pattern first created and used for book decoration in France between 1680 and 1740.

Marbling is the name given to the creation of designs and patterns on the surface of a liquid, which is then transferred onto paper or other materials. This book will concentrate on marbling paper in the traditional way, which is an old process using water-based paints floating on a jelly or ‘size’. In this book I will particularly concentrate on the history and making of marbled papers in Britain, and on the traditional patterns that are still popular today.

A Brief History of Marbled Paper

Historically there are two basic marbling traditions.

The first was found in Japan as early as 1118, and known as suminagashi. This was made by floating drops of ink on water, then a sheet of paper was placed on top and the design was transferred. These papers, apart from being works of art in their own right, were used as a background on which to do calligraphy and also as a unique security measure for documents. Suminagashi represents marbling in its initial and simplest form.

By the 1400s, the Iranian élite began migrating to the Deccan plateau of south India, where a new marbling tradition began. Lured to the region for many reasons, these poets, traders, statesmen and artists of all kinds left an indelible mark on the Islamic sultanate that ruled the Deccan until the late seventeenth century. By 1600, one Muhammad Tahir, an enigmatic Persian artist and émigré to India, was producing highly innovative marbled papers with intricately worked combed designs, used as borders for paintings or calligraphy (from Iran and the Deccan, Jake Benson, Indiana University Press, 2020). Deccan marbled drawings are occasionally illustrated, and an elaborate technique was developed using stencils outlined in gold, with painted faces added to complete the work. The marbling on these documents and figures is of a very high standard. These methods of marbling quickly spread from India to greater Iran and the Ottoman Empire.

A page from Qit’at-i Khushkhatt – a Persian album of calligraphy and marbled paper, with marbled papers by Muhammad Tahir, c.1600. (Photo: University of Edinburgh Library)

Evidence demonstrates that Turkey was the conduit by which marbling arrived in Western Europe. A fledgling decorative paper industry emerged among professional stationers in Istanbul during the mid-to late sixteenth century. As early as the 1570s European travellers to Istanbul purchased these colourful ‘Turkish papers’ and had them bound into small friendship albums (alba amicorum). These early sixteenth-century papers had rudimentary stylized drop-motifs and primitive spot patterns and have a distinctive smell of curry because the size that was involved in their making was extracted from fenugreek seed. Some of the albums containing old marbled papers still carry this distinctive smell because fenugreek was used as a size on which to float the colours in India and also in Persia.

Pen copy of the engraved portrait of the Earl of Northampton, c.1599, ascribed to T. Cockson. Pen and black ink on marbled paper. (Photo: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge)

The earliest English description of marbled paper appears in 1615. George Sandys, who travelled in the Islamic world in 1610, wrote that ‘they curiously fleek their paper, which is thicke; much of it being coloured and dappled like chamolet; done by a tricke they have in dipping them in the water.’

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries marbled patterns became more controlled and the water on which the paints were floated was thickened. Natural thickeners were used to create the jelly or ‘size’ on which the paint patterns were created. Size ingredients such as gum tragacanth became common later.

Marbled papers became a popular covering material not only for book covers and endpapers, but also for lining chests, drawers and bookshelves. The marbling of the edges of books was also a European adaptation of the art. The golden age of marbling in France and Germany ran from the 1680s until the 1730s/40s. The patterns produced there were rather beautiful and formal in their design.

By the middle of the seventeenth century marbled paper had made its way to Britain. Goods were imported from Germany through Holland – the Dutch acted as commission agents, buying and selling goods that they reexported. Marbled paper was first brought into England as wrappings on parcels of toys from Holland in order to avoid the heavy English duty tax on paper. Hence some of the earliest papers found in Britain are known as ‘Old Dutch’. The art did not fully blossom in Britain until the 1770s, and from then on it had a strong and energetic existence for the next fifty to seventy-five years.

An early example of the wide combed pattern that became known as Old Dutch.

The first known manual devoted to marbling was The Whole Process of Marbling Paper and Book Edges by Hugh Sinclair, who was making marbled paper in Glasgow around 1815. The major part of his manual was devoted to specific directions for three early patterns: Antique Spot (or Turkish), Stormont and Shell. Secretiveness was very prevalent at the time – marblers who worked in binderies tended to erect partitions to keep their marbling methods secret.

A very early example of an Antique Spot pattern shown in The Poetical Works of Christopher Pitt (Edinburgh, 1782).

A very early Stormont pattern found in the endpages of Cary’s New Itinerary of the Great Roads, both direct and cross, throughout England and Wales, 1806.

Sinclair used gum tragacanth as a medium for marbling and this continued to be used for most of the nineteenth century. The earliest and most common patterns produced by British marblers from around 1750 were the Antique Spot, Stormont and Shell patterns. Eventually marblers began to intermix the Shell and Stormont patterns with some beautiful results.

During the 1820s English makers revived the waved pattern that had been popular in Spain at the end of the eighteenth century. The British produced this pattern more precisely with very even lines of waves. Not long after this, the small combed pattern that came to be known as ‘Non-Pareil’ was introduced. These patterns were the stock-in-trade of British marbling throughout the nineteenth century.

This is an early example of marbling in Spain from Día y Noche de Madrid, published in Madrid in 1766. It shows characteristic soft colours, with waving that is charmingly irregular and in wide bands. (Photo: Ola Søndenå, University of Bergen Library)

A marbled endpaper using French Shell, from The Topography of Athens, bound in London in 1835. (Photo: Ola Søndenå, University of Bergen Library)

In 1853 a detailed description of marbling methods was written by Charles Woolnough – The Whole Art of Marbling was the first English work on marbling to be illustrated with specimens of the patterns he was describing and showed their progressive stages. Marbled paper also appeared in Laurence Sterne’s novel Tristram Shandy (1759), one of the first published books to use it.

In the 1830–80 period the introduction of mechanization into bookbinding brought about a decrease in the use and production of handmade marbled papers. Then in the 1880s there was a revival that can be attributed to Joseph Halfer, a bookbinder of Budapest. He introduced new materials and methods based on sound scientific research and wrote Progress of the Marbling Art (1885). Halfer’s discoveries published in this book made an impact that revolutionized the craft and jolted it out of the rut it had fallen into with so much factory-produced marbled paper. He advocated using carrageen moss for the ‘size’, which although known of earlier was not popular because it did not keep as well as gum tragacanth. Halfer was a chemist and worked out that adding borax to the carrageen would enable it to be kept for months. A number of highly advanced masters took up this new form and style of marbling, which is based on the production of clean, bright and detailed comb work.

A combination of Stormont and Spanish Wave from the early nineteenth century.

An advertisement for the Halfer Company Marbling Supplies. Halfer kits were available in England from at least 1890.

By the early 1920s British marbling was in a tired state, but with the production of marbled papers by Sydney ‘Sandy’ M. Cockerell it began to revive. Cockerell set new standards and published a booklet, Marbling Paper (1934), which brought the craft before a wider public and raised its status. Cockerell papers were made according to pure Halferian methods and they were produced to a high degree of perfection. His studio introduced...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 25.10.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Kreatives Gestalten | |

| Schlagworte | ART • arts and crafts • Binding • Bookbinding • books • colour work • craft • Craft Paper • Design • Designs • embellishment • Handmade • How-To • Japanese art • letter art • lines • Making • marbled • Marbling • Motif • Paint • paper • Paper Art • Pattern • Patterns • stationary • swirls • Traditional • treating paper • Zigzags |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78500-958-3 / 1785009583 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78500-958-7 / 9781785009587 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 17,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich