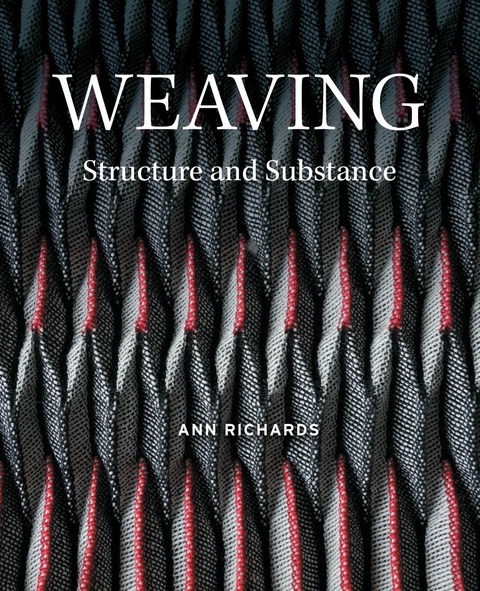

Weaving (eBook)

176 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-1-78500-930-3 (ISBN)

Ann Richards trained and worked as a biologist, before going to study woven textiles at West Surrey College of Art & Design, where she later also worked as a lecturer. She has exhibited widely, both in the UK and overseas and was awarded First Prize (MITI Award) at the Fourth International Textile Design Contest in Toyko. Her work is in many public collections, including the Crafts Study Centre, UK; Design Museum Denmark, Copenhagen; and the Deutsches Technikmuseum, Berlin. The ideas and techniques in this book are based on her experience as a designer-maker and teacher.

CHAPTER 1

Endless Forms Most Beautiful

Design in nature is hedged in by limitations of the severest kind… On the other hand, complexity in itself does not appear to be expensive in nature, and her prototype testing is conducted on such a lavish scale that every refinement can be tried.

Michael French, Invention and Evolution

Over the last century and a half interesting parallels have been drawn, both by designers and biologists, between evolution and design, and this has definitely been a two-way street, with each side seeing lessons for their own practice and taking ideas from the other. In the introduction to their book Mechanical Design in Organisms, the zoologist S. A. Wainwright and his colleagues explain their use of the term ‘design’:

The idea that biological materials and structures have function implies that they are ‘designed’; hence the book’s title. We run into deep philosophical waters here, and we can do little but give a commonsense idea of what we mean. In our view structures can be said to be designed because they are adapted for particular functions… The designing is performed, of course, by natural selection.

Writing elsewhere, Wainwright has suggested that the science of biomechanics would benefit from developing a concept of ‘workmanship’, while E. J. Gordon, in his book Structures, describes how the fabric shear produced by cutting garments on the bias of a woven fabric has proved inspirational to biologists investigating worm biology. As an aside, he mentions that he has himself used the bias cut as a source of ideas for the construction of rockets, an interesting example where the ‘soft’ engineering of textiles has been inspirational to the ‘hard’ engineers!

Robin Wootton, researching the folding of insect wings, makes extensive use of paper models to investigate the mechanisms involved and remarks on the many connections to be found with other disciplines:

When we began research on insect wing folding, we quickly discovered that the mechanisms we were identifying also occur in many other kinds of folding structures; and we found that we were talking with engineers, origami masters, mathematicians and the designers of pop-up books… in nature, similar mechanisms can be identified in the expanding leaves of hornbeams and in the respiratory air-sacs of hawkmoths.

Robin Wootton, How do insects fold and unfold their wings?

Structures such as the hornbeam leaf and the hawkmoth air-sac provide examples of a kind of ‘natural origami’ that has been widely discussed by engineers concerned with deployable structures – compact forms that can be unfolded and refolded with ease. Robin Wootton describes a number of these interesting objects, ranging from folding maps to expanding solar panels for satellites in space, before finally concluding ‘But the beetles and earwigs got there first.’

The reference to expanding solar panels concerns the fold called Miura-ori, named after the Japanese engineer Koryo Miura. Though his ultimate aim was to design deployable structures for use in space, Miura used the problems of folding and unfolding maps as a way to explore basic principles of packing flat sheets into small packages. The V-shaped fold that he worked with was already known in origami but Miura investigated the effect of using different angles on the ease of folding and unfolding and on the size of the folded package. He found that with a large angle there are limits to how small the folded package can be made, but with an angle of only 1 degree there are difficulties in folding and unfolding. He concluded that for easy folding into a very small package angles of 2–6 degrees are optimum, creating a sheet that can be unfolded in a single movement simply by pulling on two diagonally opposed corners. Most instructions currently available for constructing the Miura fold suggest an angle of 6 degrees (see Online Resources).

The Miura-ori structure shown open and partially closed. The structure can be folded completely flat in a single movement by pushing on opposing corners of the sheet.

Raspberry leaves, showing the compact folded leaf and some fully open leaves.

Ha-ori (leaf fold) shown closed and open.

The designer Biruta Kresling noticed that a similar problem of packing a large sheet into a small space occurs with the hornbeam leaf, because the bud is both shorter and narrower than the leaf that will emerge. As the leaves have a pleated structure she wondered whether the V-folds that Miura had investigated could model the process of opening and expanding that occurs when the leaf emerges from the bud. This proved to be the case and she produced the fold known as Ha-ori (‘leaf fold’), which nicely models both the lengthening and broadening of the opening leaf (Peter Forbes gives good instructions for constructing this fold). Leaves on various other plants, such as the raspberry, show similar unfolding and such examples of ‘natural origami’, together with the origami tradition itself, are very instructive when it comes to designing self-folding textiles with origami-like effects. Paper folding is a good way to experiment with the possibilities when planning a design and exploring the impact of different V-fold angles on the overall form of the piece (more detail is given in Chapter 5).

INSPIRATION FROM NATURE

Such cases of ‘natural origami’ provide good examples of nature’s ability to get there first, giving some explanation of why natural forms and processes provide inspiration for designers in all media. Architects seem particularly conspicuous in this respect, partly because of the scale on which they work. For example, it is frequently suggested that Joseph Paxton was inspired by the leaf of the water lily Victoria regia in designing the roof of the Crystal Palace, though it seems unlikely that there was a direct connection.

The water lily Victoria regia, showing the longitudinal and cross-ribbed underside of the leaf.

Paxton certainly does appear to have been impressed with the ‘engineering’ of the ribbed structure of the leaf, having posed his eight-year old daughter on one to demonstrate its strength, but the ribbing is only modestly three-dimensional, while the most notable feature of the roof of the Crystal Palace was the deeply folded ridge-and-furrow system, which had already been invented by John Loudon. Heinrich Hertel notes that this ridged structure closely resembles the pleated structure of an insect wing, though he refers also to the popular story about Paxton and the water lily.

The roof structure of Sir Joseph Paxton’s gigantic steel and glass exhibition hall, the London Crystal Palace, bears an amazing similarity to the lattice-work and articulation of the dragonfly’s wing… Paxton said he conceived this extremely fine-membered structure in his youth, as a gardener, by studying the leaf skeleton of the tropical water lily Victoria regia.

Heinrich Hertel, Structure, Form, Movement

A section of the dragonfly wing. (After Hertel)

This cross section shows the pleated structure of the leading edge of the wing. (After Hertel)

A deeply folded structure provides extra stiffness as compared with a less three-dimensional ribbed surface such as the lily leaf and the roof of the Crystal Palace certainly did resemble an insect wing. There is no evidence that the dragonfly was a direct source of inspiration for the ridge-and-furrow system, but it seems a particularly accurate analogy because the folds in the dragonfly wing are not deployable pleats – the wings are rigid structures that cannot be folded up and the function of the pleating is to provide stiffness. I have myself used the dragonfly wing as a source of ideas for pleated scarves to deal with some similar issues to those of glasshouses – a desire to combine translucency with strength and stiffness. My requirements were not exactly the same, given that I wanted deployable pleating, but stiffness was still an issue as my delicate pleats were tending to buckle and collapse. Fortunately the structure of the dragonfly wing combines longitudinal ribs with many finer cross-bars that act as ‘struts’ to support the pleating, a strategy I gratefully adopted.

Detail of a pleated fabric. Warp: Linen. Weft: Crepe silk and hard silk, with picks of linen at intervals serving as ‘struts’ to stiffen the pleating.

The ribs and cross-bars in the dragonfly wing are particularly conspicuous, but similar structures can be seen in the many insects that are able to fold their wings when not in flight, though such ribbing is often more delicate in wings that are protected when not in use. In insects such as grasshoppers and beetles the pleated rear wings that are used for flying can be folded away under hard fore wings – in the example shown here it is clear that when it comes to the process of imitating nature, this is another case of nature getting there first!

Many insects of the grasshopper family are able to conceal themselves by folding away their delicate pleated flying wings under protective fore wings that imitate leaves. (Photo: Alan Costall)

The design of many modern buildings can clearly be seen as making references to natural forms, and this theme was beautifully explored in the exhibition Zoomorphic at the Victoria and Albert Museum, together with an accompanying publication by Hugh Aldersey-Williams. One of the most prominent architects working in this way was Frei Otto who based designs on various...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.9.2021 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Handarbeit / Textiles |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself | |

| Schlagworte | Design • dye • Fashion • Interior • Knitting • Spin • Textile • UCA Farnham • WARP • weave |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78500-930-3 / 1785009303 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78500-930-3 / 9781785009303 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 61,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich