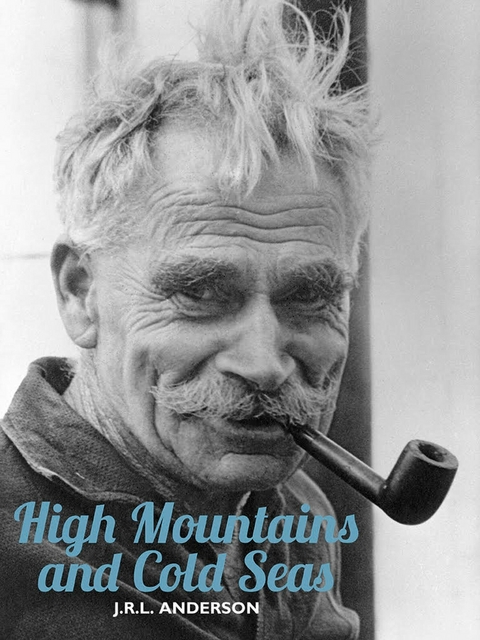

High Mountains and Cold Seas (eBook)

416 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-909461-45-1 (ISBN)

Born in 1911, John Richard Lane Anderson was a writer of poetry, fiction and non-fiction whose lifelong interest in sailing and adventure is clear from his published work. He was employed by the Guardian newspaper in Manchester from 1951 to 1967, in both journalistic and editorial roles. In 1966, Anderson led a Guardian-sponsored, small-boat expedition that built on interest in the newly 'discovered' and published 'Vinland Map'. The voyage set out to retrace the journey of Norse settlers from Greenland to the north-eastern seaboard of America. With publication of The Vinland Voyage in 1967, Anderson retired from journalism to concentrate on his own career as an author. His research for the voyage opened his correspondence with H.W. Tilman, an acknowledged expert in high-latitude small-boat voyages, and they remained friends and correspondents long after the voyage, with Anderson even attempting, unsuccessfully, to persuade Tilman to embark upon an autobiography. Anderson reflected on man's exploring instinct in The Ulysses Factor in 1970, illustrating his central hypothesis with a selection of biographical studies of explorers-some household names, others more obscure. One chapter is dedicated to the life and times of H.W. Tilman, considered by Anderson to be the very embodiment of his Ulysses factor. In 1978, the heirs to Tilman's estate commissioned Anderson to write a biography, giving him full access to their late uncle's books, letters and personal papers. With his health failing, High Mountains and Cold Seas was to be Anderson's final work and he died in 1981, shortly after it was first published. Long out of print, High Mountains and Cold Seas has been republished as a companion volume to the new complete edition of Tilman's fifteen original works.

ANDERSON’S BIOGRAPHY OF H.W. TILMAN is the reason I wrote my own. I thought I could do better, make Tilman more accessible and bring out the innate humour of the man more readily. Time has made me re-evaluate both my own efforts and Anderson’s, and it is by no means a criticism to say I believe that, in the final analysis, we both failed, but in different ways.

Anderson goes for the hard-nosed approach, and the title of his book says it all, preferring to show Tilman as a tough man of heroic—if not epic—dimensions, forever striving for perfection, seeking Valhalla in his endeavours yet finally, inevitably, finding a lonely death in the icy waters of the South Atlantic.

Read Anderson’s book, then, for one view of the man; read Tilman’s own books to seek the complex truth—or at least part of it. The subject remains in many ways, thankfully, an enigma; as he would have wished.

Perhaps the key question, though, is why does Tilman’s life matter? It is a far easier question to answer than who, exactly, this unique and extraordinary man was—and what motivated him.

The age of heroes may be over; we live in a much shallower, short-term world, in which fame is instant and instantly forgotten, where notoriety is a key, shouting the most and at the highest volume lauded as some weird virtue.

Tilman, on any assessment, was a hero, and in the most obvious sense. A Victorian gentleman to the end (two words that once resonated with historical, geographical and cultural force) he was also a shy, self-effacing and thoughtful wise man, who kept his counsel, more often than not, and whose books display a huge sense of the absurd, in their dryly comic narratives.

Rich enough at 40—inheriting money from his father’s estate—to indulge his passion for exploration, his raison d’être may be found in the mud and blood of the trenches of the Great War. It should never be forgotten that his character was forged—by a terrible accident of history—by conflict in its most brutal industrial form. Surviving a first world war, although badly injured at one point, he was plunged back into a second.

I have, in my possession, two photographs of Tilman, one taken on the Everest expedition of 1938, when he was 40; he looks like a teenager. The second was taken in Nepal in 1948, ten years later. Mischief is written across his face, animated by the presence of a ‘famous lady explorer’, Betsy Cowles, standing next to him, but it is the picture of an old man. The Second World War did what the first miraculously had not; aged him.

If you want to understand the man, you have to understand Tilman the soldier. There is the heart of the matter; the soul of the man. But it is not as easy as that: Tilman was not a conventional soldier, never one to obey orders and slide up the ranks to conventional military fame and fortune. Something of the rebel adolescent remained all his life. And there is more: survivor’s guilt, borne of the slaughter surrounding Tilman in the trenches.

It is worth running through the key elements of Tilman’s career as a soldier, and to set them against his life apart from war. There is much to learn from what he wrote of himself as well of the Second World War. Like many others in the conflict, he never wrote about the first: what, after all, one may legitimately ask, was there to say?

Tilman entered the Great War as a very young subaltern in the Royal Artillery. He rapidly gained a reputation for volunteering for observation post work, which meant being alone in no man’s land with a field telephone and a pair of binoculars, observing the fall of shot. Lonely work, dangerous work, not for the faint-hearted. But he survived where many others did not; being on his own enabled him to take complete management over the odds against him.

It’s worth considering whether, if times had been different, he might not have found his greatest solace in single-handed yacht sailing. Between the world wars he farmed in East Africa, a lonely pursuit; he met Eric Shipton and together they forged one of the greatest climbing and exploring partnerships in history. Two men against the elements, suiting each for his own reasons. Their climbing and exploring in Asia have rightly become the stuff of legend.

The Second World War saw Tilman back in the artillery, where he sloshed about for the first three years, not rising above the rank of major, and definitely not wanting to—his own words spell that out clearly. Only when he found he could get himself into special forces training did his personal war become, paraphrasing his words ‘worthwhile’. Dropped first into Albania, then northern Italy, in both countries he became another kind of legend. Notably in Belluno, in Italy, which still celebrates a Tilman Day, and where locally exists a Via Alta da Tilman—a kind of one-man Pennine Way, based on his alleged progress with the guerrillas in the latter part of the war—Tilman’s status as a true hero is immortalised. Despite his shyness, his self-effacement, I believe in this aspect the man would have rightly swelled with pride.

The war ends, Tilman is approaching fifty. For the next half dozen years his life loses focus. It is easy to see he simply does not know what to do. A stint as a servant of empire in Burma (Eric Shipton had got himself fixed up as the consul in Kashgar), and a few mountain expeditions, from one of which, on Ben Nevis, he had to be rescued by boy scouts. One last look at the Himalaya in a notable trip to Nepal, where he met Betsy Cowles, and he turns his back on the high mountains of Anderson’s title.

Then comes the sea, the element that is to dominate the rest of his life. A battered Bristol pilot cutter called Mischief, a gaff-rigged sailing boat, becomes the great love of his life. With Mischief, Tilman finds the sailing equivalent of climbing with Eric Shipton, except that with the boat, there was the advantage of her not talking back, and her Skipper could show her all the love he had to give.

It all worked well, for many years, but his first sailing companions, largely, but not entirely, ex-army chums, grow old and tired, whereas Tilman cannot give up his life-long restless quest for peace. As his crews grow younger, Tilman grows more distant, harder to understand—quite literally toward the end, as he became increasingly hard of hearing.

Mischief was eventually lost to ice damage in Greenland in 1968; Tilman wrote an extremely moving, privately published obituary. It is heartbreaking to read, his anguish at this loss perhaps encompassing a greater, earlier and more visceral grief.

After his beloved little ship was lost, Tilman tried, with increasing desperation, to recreate the voyages he made in Mischief, with decreasing success. He made, in all, eight voyage to Greenland or its environs, and lost another Bristol pilot cutter in so doing.

Finally, he had to admit, he was getting too old to continue, having to fly back ignominiously from Iceland, abandoning his last ship, Baroque, in Reykjavik. It looked to be all over.

Then came a last call, from a young former sailing crew member, Simon Richardson, asking if he would be the navigator on a voyage Richardson planned to Smith Island in the Antarctic. Tilman had failed to reach this destination years before; and it rankled as an abject failure. On that voyage, an experienced crew member had inexplicably been lost overboard at night in the Atlantic, the single casualty suffered in 140,000 miles of sailing.

The ship chosen by Richardson was a conversion, a former tug with a keel welded on by Richardson. She reached Rio, then sailed south, never to be seen again. Bill Tilman has no known grave, other than the seething cold black waters of the South Atlantic.

The young men who went to war in 1914 became a lost generation. Part of their tragedy was that many who sent them to their death believed the decadent world they grew up in needed to be cleansed—by their blood. They spilled enough of that, most deaths, incidentally, caused by artillery shells. Those who survived carried a unique burden for the rest of their lives.

Tilman chose solitude, as much as he could, and we can easily understand why. He chose, though, to write a great deal about his exploits and in so doing showed us a rare, a brilliant, talent for travel writing and for darkly dry humour. It no doubt was a solace, the writing and the exploring: Africa, then mountains, finally remote corners of the globe by sailing ship from the immortal sea.

H.W. Tilman was stoic by nature, a man of honour and great courage, forthright and faithful, a man of his word and, increasingly, out of his time.

Why does he matter—and he does, a great deal? Because he demonstrates the truth of a line from Horace:

Nil mortalibus ardui est (nothing is impossible).

But the line has two senses and may, more subtly, be translated as ‘nothing is beyond the capability of man’. In this translation, there is both yin and yang, good and evil. We have a choice, always. Tilman saw that in the wars he fought.

And Tilman, true to the end, unerringly chose the better, the harder, more arduous path.

We could all learn a great deal from that, and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.9.2017 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | H.W. Tilman: The Collected Edition |

| H.W. Tilman: The Collected Edition | |

| H.W. Tilman: The Collected Edition | H.W. Tilman: The Collected Edition |

| Vorwort | Tim Madge |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Segeln / Tauchen / Wassersport | |

| Schlagworte | Anderson • Atlantic travel • baroque • Betsy Cowles • Bill Tilman • boating book • Bob Comlay • Cold Seas • Dr Charles Houston • Eric Shipton • expeditions • expedition writing • Glaciers • Greenland • high mountains • H W Tilman • H.W. Tilman • Iceland • Joan Mullins • J.R.L. Anderson • JRL Anderson • Karakoram • Karakorum • Kenya • Lecky's Wrinkles • mischief • Mischief goes South • Nanda Devi • Pam Davis • pilot cutter • Royal Artillery • sailing book • sailing in the north • sea breeze • Simon Richardson • Spitsbergen • Spitzbergen • The Last Hero • Tillman • Tilman • Tilman books • Tim Madge • Travelogue • Travel writing • voyages |

| ISBN-10 | 1-909461-45-8 / 1909461458 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-909461-45-1 / 9781909461451 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 37,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich