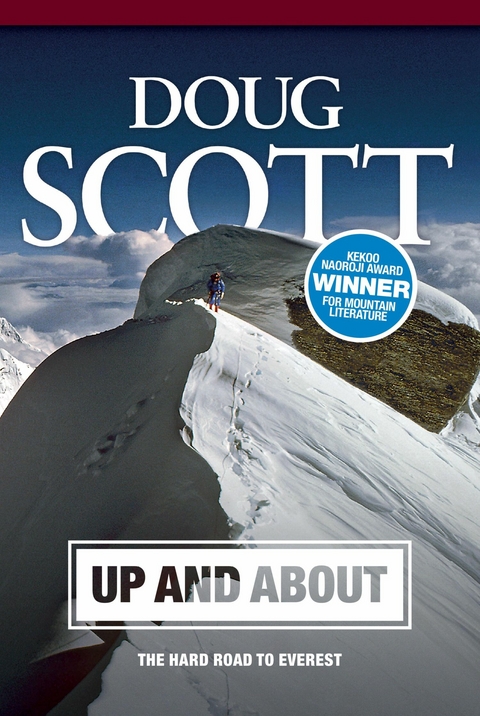

Up and About (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-910240-42-7 (ISBN)

– The 3rd Age –

And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow.

As You Like It, William Shakespeare

The idealism of youth which brooks no compromise can lead to over-confidence, the human ego can be exalted to experience godlike attributes but only at the cost of over-reaching itself and falling to disaster. This is the meaning of the story of Icarus, the youth who is carried up to heaven on his fragile, humanly contrived wings, but who flies too close to the sun and plunges to his doom. All the same, the youthful ego must always run this risk, for if a young man does not strive for a higher goal than he can safely reach, he cannot surmount the obstacles between adolescence and maturity.

Carl Jung

– Chapter 5 –

Jan

The Nottingham contingent of the Oread Mountaineering Club at Darley Dale in 1959. On the wall, L–R: Wes Hayden, me, Geoff Hayes, Ken Beech. Standing, L–R: Mary Shaw, Beryl and Roger Turner, Annette Rabbits, Mike and Celia Berry.

Wearing my new duffle coat, I took a bus down to Loughborough in September 1959 to begin two years of teacher training. My first lecture, on how to conduct a PE lesson, was called ‘Maximum Activity in Minimum Time’ and was given by an ex-professional footballer called Archer, who peppered his talk with phrases like ‘man in terms of himself’ and other such jargon. It was obvious to me and probably everyone else in our group that those who had completed two years of National Service were more mature and worldly wise than those of us who were eighteen and had not had a break from education. I would have gained far more from the course if I’d had the courage to take time out to work or travel for a year or so.

During my first term the anatomy lecturer, with the help of third-year students, had our group lined up in the sports hall, stark naked, to be somatotyped. In turn, full-length photographs were taken of our bodies – front, back and side. Our percentage of fat was measured by a third-year using callipers to grip our folds of flesh, and many other measurements taken to determine our position on a three point graph devised by Dr William Sheldon of Columbia University. He had devoted his life to showing there was a correlation between body type and personality. To this end he had produced a book, Atlas of Men, containing 1,175 naked examples of somatotypes at various Ivy League universities. An ‘atlas of females’ was in the pipeline but never appeared as Sheldon’s methods and underlying philosophy were increasingly being questioned. The idea was linked with eugenics, a controversial subject with Josef Mengele still on the run.

My physique was expressed in relation to three main types: endomorphs, who have a tendency towards plumpness with wide hips and narrow shoulders and who, according to Sheldon, are generally tolerant, good-humoured, fun-loving, enjoy comfort and are quite extrovert; mesomorphs, who have a strong, muscular body, are broad shouldered, narrow at the waist and tend to be temperamentally dynamic, gregarious and assertive risk-takers; and ectomorphs, who are slight with narrow shoulders, thin limbs and little fat and are often artistic, sensitive, introverted, thoughtful, socially anxious and keep themselves to themselves. The anatomy lecturer told us the majority of suicides at universities were from this group. I remember being a little anxious not to be from this group, but as it turned out I was a mesomorph.

I got hold of a book circulating at the time with all the associated characteristics outlined. On the physical side, it said people like me were prone to abdominal hernias, something I was suffering from at the time, and that got me reading more, especially about a mesomorph’s tendency towards aggression. I wanted to know why, as a boy, I enjoyed smashing my broken Hornby train on the concrete yard and then pounding it with the coal hammer. Mrs Boothwright next door had been watching from her bedroom window and called down: ‘you are a destructive little boy, aren’t you Douglas?’

I had regiments of lead soldiers, all immaculately painted in bright colours, until I discovered they could be melted down in a saucepan over the gas stove. I watched them, fascinated, as they became silvery blobs and then the whole regiment coalesced into a single pool of metal. There were moments of madness, like the time, going home from school, I leapt on to a parked car and ran along a whole line of them. The hernia I got fixed in Nottingham General Hospital, waking up to hear Hancock’s Half Hour on the ward’s black and white TV, and trying not to laugh. The character flaw would be harder to fix.

In general, my somatotype suggested characteristics that I recognised. I was indeed energetic, always on the go, often taking risks in everything I did. I could be gregarious and didn’t always consider the needs of others. I could be competitive when I got the bit between my teeth, although by the time I was eighteen I must have reached saturation point when it came to collecting awards. I had enough ‘strings to my bow’, as Dad called them. In a doctrinaire fashion, I decided what mattered most was taking part, not receiving certificates. With this sudden realisation I refused to go to Buckingham Palace to collect my Duke of Edinburgh Gold Award, much to the consternation of Nottingham Council, which hosted the pilot scheme. It was also a concern for Everest leader John Hunt, who headed the award.

A meeting was arranged at Nottingham Council House, the grand city hall, for me to explain myself to John Hunt himself. He proved sympathetic and I did eventually receive my certificate from my brother Brian, who collected mine at the same time as being presented with his at Buckingham Palace. My sudden reluctance for conventional channels continued at college where I was surrounded with top athletes, county rugby players and swimmers representing their country, all of them hungry for gold and glory. This may have had something to do with my ethical stance. I remember the great delight I felt when one of these heroes came up to me in the refectory and pointed to the college newsletter where I was praised for climbing Joe Brown’s classic climb, Cenotaph Corner.

I didn’t spend that much time at college, preferring to go climbing over the long weekends, working on the farm on Wednesdays and so reducing college to two days a week. My first year passed in a haze of lectures, teaching practice, sitting up late to write assignments, and practical lessons on how to teach swimming, athletics and major games. I coped and even found some of it interesting. At the end of my first year, I put a lot of thought and research into an essay on Bertrand Russell’s theme of authority and the individual, but my English tutor, the brother of the politician and journalist Woodrow Wyatt, lost the fifty-odd pages I had so carefully hand written for the third time. He wasn’t that apologetic although he did say he liked it.

My first stint of teaching practice took place at the William Crane School, Nottingham. I was fortunate to have assigned to me a dedicated teacher with a calling for the job. He gently enthused me for the profession and for teaching underprivileged children. He let me into the background of each child, so many of them living in difficult circumstances; most were simply crying out for someone to care for them. Under his guidance I connected well with the class and ended up with a good report; most of all I was touched by the boys’ genuine sadness when I came to leave at the end of my practice. I am sure that a couple of days walking in Derbyshire with them had helped to bond us together.

At the end of the summer term, I hitchhiked to Chamonix where the weather was terrible. I mostly sat around the Chalet Austria, a scruffy hut near Montenvers where we could stay for free. The rising rock-climbing star Martin Boysen was there, and also Wes Hayden and other frustrated Nottingham lads. Early in August I gave up and hitched to the Écrins to meet two new college friends, Lyn Noble and Mark Hewlett. We based ourselves at La Bérarde, a summer settlement in the lovely unspoilt Vénéon valley, so different from Chamonix. Over the next four days, we completed a marvellous circular tour over Pic Coolidge, the Dôme de Neige and the Barre des Écrins, dropping down to the village of Ailefroide and returning via the Col de la Selle.

Towards the end of August I left the Alps, hitchhiking south to Morocco with the aim of climbing Toubkal, the highest mountain in North Africa. I walked five miles in humid heat from one side of the splendid city of Arles to the other and then meandered through the amazing étangs of the Camargue, incongruous in big mountaineering boots and carrying a rucksack with rope and ice axe on display. I plundered an orchard of the sweetest, most succulent pears I’ve ever tasted, but had to share them with my next benefactor as we sped through the countryside in his sports car. A year ago I had been close to the source of the Rhône, now it was a mighty river, loaded with Alpine sediment, pushing on into the Mediterranean.

I had arranged to meet Brian and a friend at Le Grau-du-Roi post office but it was shut for a festival, so I left my sack outside and went off to scour the beaches and narrow streets of this pretty fishing village for any sign of him. Brian came into view, fit and tanned, wearing my old sweater with his school friend Boris walking alongside clutching a bottle of rum. It was so good to see them and catch up, ranting on for hours at their campsite, sharing travellers’ tales. We set off for Barcelona, but I...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.11.2015 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Schlagworte | Chris Bonington • climbing books • dougal haston • doug scott mountaineer • facts about mount everest • Mount Everest • mount everest facts • Mt Everest • Nepal |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-42-7 / 1910240427 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-42-7 / 9781910240427 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 38,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich