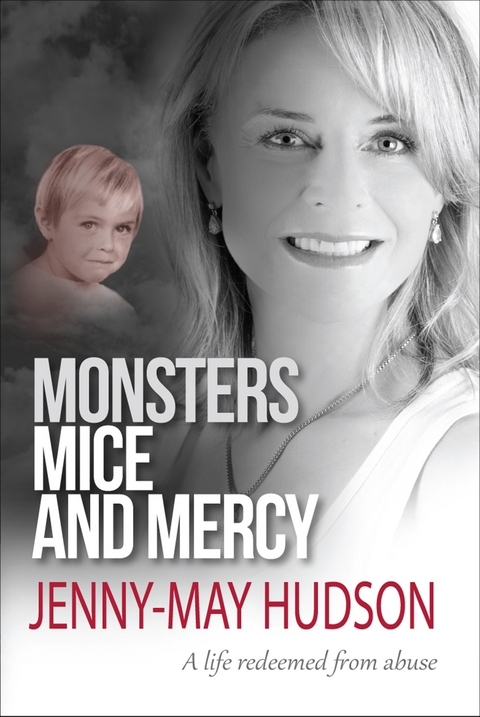

Monsters, Mice and Mercy (eBook)

288 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-85721-462-1 (ISBN)

Jenny-May Hudson grew up in Pretoria, South Africa, the third child of an Afrikaner father and a British mother. Her childhood was horribly marred by her domineering father, who beat her mother, showered blows and insults on his children, and micro-managed the household with weapons, mind-games, and violence. Ironically, his tactics would come back to haunt him. The years of pain would leave Jenny-May with grim memories. Yet through the power of Christ a transformation was in store. Today Jenny-May is whole and happy. She and her husband Elmore, and their three children, have relocated to Perth, Australia. Jenny-May has developed a considerable speaking ministry, and her journey ' from abuse to self-acceptance and joy ' has become a source of inspiration to thousands. This book demonstrates that nothing can hold you captive without your consent.

Chapter 2

Since my mother, Doreen Ann (née Wheble), was British, and Dedda was Afrikaans, they reached a “democratic” agreement: she had to shun the country of her birth, never mention the “parasitic British Royal Family”, and learn the Afrikaans language.

Also, my father bundled all of us children into Afrikaans schools. Our Grade 1 reader was entitled Baas and Mossie. It was about a parrot, Baas, and a little girl, Mossie. Every time the girl lost something, the parrot would shout, “Soek hom, soek hom, roep Baas!” which means, “Look for it, look for it, calls Baas!”

Without fail, Mamma would instruct us to find our shoes, clothes or the like, and we would protest at not being able to locate the items. She would gleefully say with pride, in a strong accent, “Sook hom sook hom rup Baas!”

Her Afrikaans was not so hot, but she tried hard. I recall my father’s conservative church-going family were on a rare visit to our home when Mamma announced, “Gistraand, dit was so warm, ek het bo-op die diaken geslaap.” She was trying to say, “It was so hot last night, I slept on top of the bedspread.” But to her horror, she discovered that she had blurted out, to screams of laughter, that she had slept on top of the church deacon! A deacon in the church is a very pure and noble man. She fled the room, professing never to speak “that ____ language” again.

The Afrikaners of the Apartheid era were very inflexible about their language. If you could not address an Afrikaner in their own language, some would simply ignore you, or converse with disdain. To this day, there are some diehard shop assistants and business folk that will only speak Afrikaans, even though you initiate the conversation in English. However, this is more the exception than the rule, as South Africa has come a long way since the days of Apartheid.

Mamma complied with the “democratic” agreement they reached early on in their relationship, and if she mentioned “the ____ British Royal Family” or “the Leech ____ British Queen”, Dedda would help her to remember the deal. Should she mention England, he would down the country, the prime minister, and the pound, and would soon smother any thoughts she had of the country of her birth. It would be thirty years before she went home, and in fact I toured England before she did.

Her mother was also free game, and my granny was public enemy number one in the eyes of my father. Martha Jane Wheble Welman (and sometimes Summerton) wove in and out of our lives, as my father’s moods dictated. For years she would be acceptable, then she would be banned from our home, then welcomed back into the fold, only to be banished again. We had to visit her in secret, and Mamma made us promise not to tell.

At one time, Mamma convinced Granny to seek forgiveness for a misdemeanour she was unaware of having committed, and as she approached, Dedda did not even grace her with a look. Without disengaging himself from his task, he simply stated: “I have no desire to talk to you, Mrs Welman.” I thought he had slipped up, because Granny was married to Dick Summerton (whom I affectionately called “Goempah”). Perhaps he had forgotten that Mr Welman, the man my mother detested, had died. But my father was deliberate. He was blackmailing Granny; he knew her secret, and he was ensuring that she would not persist with the conversation. In his eyes she had no right to use her married name, Summerton, and he was giving her a message: “Back off, or I will expose you.” She left in a flood of tears. Our visits to Granny reverted to being conducted in secret.

By the time I was ten, I knew loads of secrets, and many monsters. Some even lived under my bed. The secrets and the monsters had the same DNA. Dark, hidden, scary. Secrets loitered in my eyes, and I was afraid people might accidentally see them, as my brain was so overcrowded. I hated the secrets. They kept wanting to escape, which meant trouble. So I kept them inside, but as they were there to stay, I had to make room for them.

Granny was one of the better secrets I knew. Visits to Granny were wonderful. She lived in a tiny house in Tram Street, Pretoria, next to Ginsberg’s Supermarket, where she worked. This was across the road from the park, and a block away from the Austin Roberts Bird Sanctuary. Granny would take us to the swings, and then down to feed the birds through the wire fence. There were ostriches prancing up and down the fence. The males were black and white, and the females resembled bland, grey feather dusters with beaks. I used to be fascinated to see these big birds eating small stones to aid digestion, and I was certain that this was what made them too heavy to fly. Beautiful blue cranes pranced past our starry eyes, and tortoises were scattered here and there. A camouflaged passageway, covered in reeds, led us to the centre of the sanctuary at the water’s edge. We would shout excitedly while pointing to the birdies as they took off in fright, with Granny hushing us all the while. We soon grasped that this was a quiet place, and tiptoed to the vantage point with the wooden floorboards creaking under our feet.

Granny had a special cupboard below her kitchen sink from which we could choose sweeties she kept just for us: Manhattan Gums, Senties and Gum Bears. We would go to the cupboard and choose a box, and have it all to ourselves. I used to feel spoiled and exhilarated. Occasionally, when she was not a secret, we were allowed to sleep over at Granny’s, and I remember curling up on the lilac rug next to her bed, while her bedside clock tick-tocked me to sleep.

My Granny was Welsh. She came from Merthyr Vale in Mid Glamorgan in South Wales. She spoke highly of her parents, a coal-mining family, and was the sixth of seven children – four boys and three girls. Violet was the eldest, followed by William, who died at eleven months. James died at age four and Thomas at twenty-one. William was born on 7 January 1911, followed by my grandmother in 1913. Betty died at eleven months, and Vivien, the last-born, arrived in 1923.

At age nineteen, after relocating to London, Martha Jane Evans fell in love with twenty-two-year-old Jack Wheble and married him on 22 July 1933 at the Parish Church of Saint Swithun, Hither Green. On 28 February 1935, she produced a daughter, Sheila.

On my granny’s birthday, 3 September 1939, Great Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. On 7 September 1940 the Blitz began. London was bombed by the German Luftwaffe until 16 May 1941, when most of the Luftwaffe was reassigned for the invasion of Russia, which was imminent. During the Blitz millions of British children, mothers, hospital patients, and pensioners were evacuated to the countryside. For those left in London, blackouts began. Every building had to extinguish or cover its lights at night. My granny, heavily pregnant with my mother, took cover in her garden in an underground bomb shelter which she shared with her sister-in-law, Lillian, who lived next door.

Granny told of a terrifying morning when a Spitfire was shot down by a Messerschmitt Bf109 and crashed into Auntie Lilly’s home next door. The engine and propeller burrowed on through the earth alongside the bomb shelter, down the full length of Auntie Lilly’s garden and through the neighbour’s adjoining garden at the far end, before coming to rest just metres from the neighbour’s house. Auntie Lilly had run back into the house to fetch her handbag, and on her return was trapped in the entrance of the shelter at the moment of impact. Her face and arm full of shrapnel, she was taken to hospital in an ambulance. Granny and little Sheila were buried alive in the shelter, and once rescued by firemen, were taken to the hospital in the fire engine. Jack came home to chaos, and it took him hours to locate his family, as no one seemed to know which hospital they had been taken to.

Three weeks after being dug out of the shelter, on 18 October 1940, during the persistent nightly bombings, Granny went into labour. She gave birth to my mother in near-impossible circumstances, and brought life into the world as countless thousands were dying during World War II. Mamma survived in more ways than one, as she fought for her right to survive in the womb despite her mother’s unsuccessful attempt to terminate her pregnancy.

When Mamma was six weeks old, her father Jack was sent to Aldershot for six months’ training, returning briefly for short leave in Wales to visit my granny and the family and then on to training in Scotland before being sent to Singapore, where he was captured by the Japanese. My grandfather was a prisoner of war, who in 1943 was forced to build the Bangkok– Rangoon railway bridge over the river Kwai in the Burma– Thailand jungle. Gunner Jack Wheble from 3 Bty. 6 H.A.A. Regiment, Royal Artillery, died aged thirty-three on Monday 7 August 1944 in a Japanese concentration camp from malaria and dysentery. The only things my granny ever received back from her husband were a watch and dog-tags covered in lime (used to prevent the stench of decay in mass graves).

World War II came to an end in 1945 when Mamma was five. Granny told us how Mamma used to rock herself in an attempt to find comfort during those scary times when planes, bombs, underground shelters, and the dark infiltrated her little world. At the age of three and a half, Mamma, with her older sister Sheila, was placed into boarding school. Granny could not afford the full fees, so her girls had to work...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 23.8.2013 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 8pp colour photos |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Pastoraltheologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-462-4 / 0857214624 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-462-1 / 9780857214621 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich