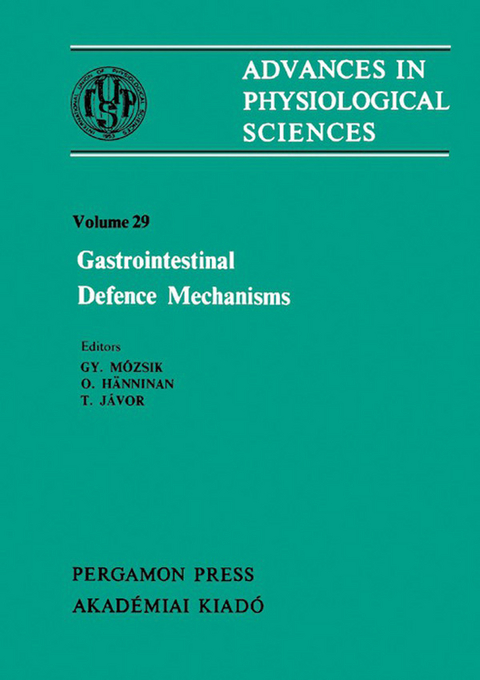

Gastrointestinal Defence Mechanisms (eBook)

606 Seiten

Elsevier Science (Verlag)

9781483190181 (ISBN)

Advances in Physiological Sciences, Volume 29: Gastrointestinal Defence Mechanisms is a collection of papers that details the findings of research studies on the theoretical and practical aspects of the gastrointestinal defense mechanisms. The title first covers circulation and mucosal defense, and then proceeds to tackling the association of gastrointestinal mechanisms with the secretory functions. Next, the selection deals with the resistance in gastric mucosa and mucosal energy provision. The text also discusses cell renewal and toxicity, along with biotransformation and nutrition. In Part VII, the title details the immunomechanisms of defense at mucosa. The last part covers the second line defense at liver and enterohepatic circulation. The book will of great interest to both researchers and practitioners of medical fields concerned with the digestive system.

CIRCULATORY RESPONSES TO CHANGES OF INTESTINAL CONTENTS

G. Szabó and I. Benyó, Traumatological Research Unit and Third Department of Surgery, Semmelweis University Medical School, Budapest, Hungary

Publisher Summary

This chapter discusses experimental results on circulatory responses to changes of intestinal contents. The maximal increase in mesenteric blood flow is 150–200% but usually the augmentation is well below 100%. The blood flow has been measured to the gastrointestinal tract as a whole. The composition of the ingested food and its degree of digestion might be an important factor in the production of the gastrointestinal flow response. The concentration of nutrients in the jejunal lumen must exceed a certain value to produce local hyperemia and, generally speaking, the greater the concentration of nutrients in the chyme, the greater the resultant hyperemia. It has been reported that gastrointestinal hormones might play an important role in the postprandial intestinal vascular alterations. Shunts do not exist and accordingly, the redistribution of flow cannot occur. During vasodilatation elicited by intraluminal glucose or food, the spheres impacted in the deeper layer might migrate to the mucosa and consequently produce an apparent redistribution of intestinal blood flow.

Metabolic and circulatory changes during digestion and absorption of food were analysed already by Brodie et al. in 1910. Many studies have since confirmed that blood flow in the superior mesenteric vascular bed increases following a meal. This postprandial mesenteric hyperaemia has been observed in man /Brandt et al., 1955; Degenais et al. 1966/, conscious primate /Vatner et al. 1974/, anaesthetized and conscious dogs /Burns and Schenk, 1969; Fronek and Stahlgren, 1968; Varro et al., 1967; Vatner et al. 1970/ and rats /Reininger and Sapirstein, 1957/. The blood flow through the superior mesenteric artery in dogs starts to increase within 5 to 15 min following food intake, reaches a maximum in 30–90 and lasts for 3–7 h /Burns and Schenk, 1969; Fronek and Stahlgren, 1968; Vatner et al. 1970/. If food constituents are introduced directly into the duodenum the circulatory reaction begins in less than 10 min /Chou et al. 1976/.

The maximal increase in mesenteric blood flow is 150-200% but usually the augmentation is well below 100%. This seems to be a rather moderate increase because propranolol e.g. may produce a much greater augmentation of flow /Lundgren 1967/. There might be several reasons for the moderateness of this prostprandial vasodilatation. In the above studies the blood flow was measured to the gastrointestinal tract as a whole. It seems unlikely, however, that maximal vasodilatation occurs simultaneously in ever part of it. The vasodilatation might be localized to the mucosa with no or only moderate changes in the perfusion of the muscular layer. It seems that intestinal motility as such does not increase significantly total intestinal blood flow /Lundgren 1967/ and that the absorption of certain foods may not induce any conspicious flow changes /Brand et al. 1955/. The composition of the ingested food and its degree of digestion might be an important factor in the production of the gastrointestinal flow response. Moreover, certain food constituents may increase the blood flow in some part of the gastrointestinal tract, but be without effect on the circulation of other parts. Let us see a few examples for the above propositions.

While undigested food introduced into the duodenal or jejunal lumen failed to increase venous outflow from the exteriorized intestinal loop, digested food or its supernatant increased it significantly by 13% and 11%, respectively /Chou et al. 1976, 1978/. In the jejunum bile alone had no effect, but introduced in the ileal lumen it increased local blood flow and it also markedly enhanced the hyperaemic effect of digested food in the jejunum. Glucose solution increased the circulation of the isolated jejunal loop in the dog /Varró et al. 1967/. The intestinal hyperaemia is limited, however, only to the perfused teritory /Van Heerder et al. 1968/ and the increase of flow occurs mainly in the mucosal layer /Yu and al. 1975/. Intraduodenal fat augmented flow in the cat superior mesenteric artery by 50-100% /Fara and al. 1969/. At physiological postprandial concentrations in the jejunum micellar solutions of oleic acid and monoolein increased flow, but 16 common dietary amino acids did not. The hyperaemic effect of lipids required the presence of taurocholate /Chou and al. 1978/.

The concentration of nutritients in the jejunal lumen must exceed a certain value to produce local hyperaemia and, generally speaking, the greater the concentration of nutritients in the chyme the greater the resultant hyperaemia. The differences in circulatory effects are, however, not due to differences in the osmolarity of the solutions since an unabsorbeable substance with the same osmotic concentration does not increase intestinal blood flow /Kvietys and al. 1976/.

It seems, however, that the composition of the ingested food is not the only factor leading to haemodynamic changes. It was only recently realized that the cardiovascular system responds to feeding in two distinctly different phases. During presentation and ingestion of food cardiac output, heart rate arterial pressure and vascular resistance in various vascular beds are altered in a pattern similar to that observed at the increase in sympathetic neural activity. Within 5ndash;30 min, however cardiac output, heart rate, arterial pressure, the perfusion of the kidney and of the myocardium return to control levels, while mesenteric blood flow starts to rise. In humans anticipated feeding increases also vagally mediated gastric acid secretion /Moor and Motoki, 1979/. Pure psychic stimulation may be as effective stimulant as feeding. The observations suggest that in the first phase the anticipation and/or ingestion of food elicit a secretory and generalized cardiovascular reaction, in the second phase i.e. during the digestion when the ingested food reaches the intestines there is a circulatory response confined to the digestive organs /Burns and Schenk, 1969; Fronek and Fronek, 1970; Vatner et al., 1970, 1974/. On the other hand some textbooks state that there are nervous receptors in the walls of the duodenum stimulated by high concentration of hydrogen ions and that the acidification of the duodenal contents leads even in absence of any food to marked changes in gastrointestinal macro- and micromotility and secretory activity. The automatic movements of the intestinal villi are stimulated and their capillaries are dilated /Ludany et al. 1959/. The hepatic blood flow, measured with coupled thermoelements, hydrogen wash-out technique or BSP-clearance is significantly increased /Benyó et al., 1965, 1966, 1974/.

In the studies about the effect of various nutritients on gastrointestinal circulation usually only the superior mesenteric artery flow /SMAF/ has been measured. There are only a few informations available concerning the effect of a meal on coeliac artery flow, which supplies the liver, stomach, duodenum and pancreas. In order to gain information about the flow changes in the whole splanchnic vascular bed in the first series of our experiments we have studied in dogs with non-cannulating electromagnetic flow probes the effect of acidifying the duodenal contents on the blood flow in the hepatic artery and in the portal vein.

In 13 mongrel dogs the basal blood flow in the hepatic artery /HAF/ was 13.6 (SEM ± 1.3) ml / min/100 g tissue weight in the portal vein /PVF/ 46.6 ± 7.0 and total hepatic blood flow /HBF/ was 53.5 ± 6.3 ml/min/kg. After the introduction of 3 ml/kg body weight 0.1 M hydrochloric acid into the duodenal lumen HAF increased by 24.7%, PVF by 31.3% and HBF by 29.2%. Maximum HAF change was attained in 2 to 7 min and the reaction lasted 8 to 30 min. The arterial and venous reaction:-were usually not entirely synchronous. In the first minute after acid introduction there was usually a drop in arterial blood pressure, after which it returned to nearly control level. At the same time there was a small increase in portal venous pressure. Hepatic artery inflow resistance decreased by 11%. The most prominent change was the 32.5% drop in mesenteric arteriolar resistance. /Fig. 1, Fig 2/

Fig. 1 Effect of duodenal instillation of 0.1 and 0.5 M hydrochloric acid on hepatic artery /AHF/, portal vein /VPF/ and total hepatic blood flow /HBF/ in anaesthetized dogs.

F: blood flow, ml/min/100 g organ weight. White columns: before acid introduction; Shaded columns: after acid.

Fig. 2 The effect of duodenal acid introduction /arrow/ on arterial pressure /AP/, portal venous /PVF/ and hepatic artery blood flow /HAF/.

These experiments have shown that the introduction of acid into the duodenum leads to a transitory increase in mesenteric blood flow lasting about 30 min. If it is supposed that the flow reaction is due to chemoreceptor stimulation, it can be assumed that a stronger stimulus would elicit a greater response and that a prolonged stimulation leads to a sustained flow reaction. Actually in 5 dogs 3 ml/kg 0.5 M hydrochloric acid introduced...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.10.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Krankheiten / Heilverfahren |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete | |

| ISBN-13 | 9781483190181 / 9781483190181 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich