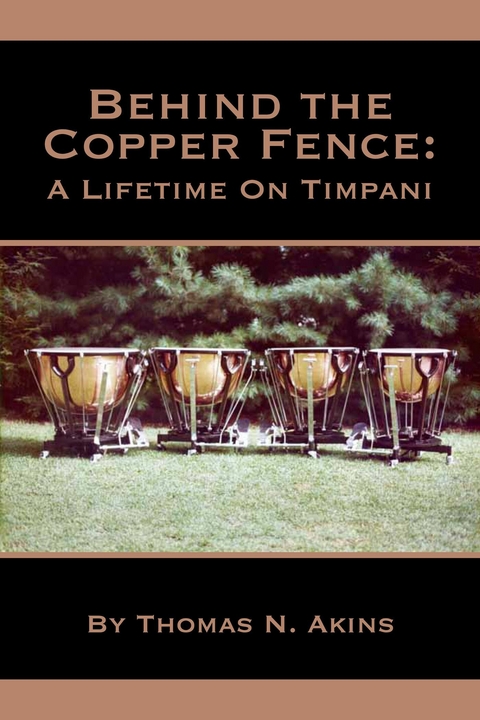

Behind the Copper Fence: a Lifetime on Timpani (eBook)

213 Seiten

First Edition Design Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-62287-368-5 (ISBN)

For 26 years I had the best seat in the house - often in the center of the stage, frequently in the spotlight, always in the clear view of conductors and the audience and constantly amid the passions that come with making good music. This is the story of how I got that seat.

1 - But Mom, I Want To Play Drums

As fall pushed into winter, I pushed closer to the door. The door of the band room, that is. I was an eighth-grader at William Fleming High School in Roanoke, Virginia, a school that educated students from grades eight through twelve. To accomplish this in a building that was designed for several hundred less bodies than the number that bumped into each other during each class change, the school adopted three schedules. They were quickly dubbed “early,” “regular” and “late.” The “early” schedule ran from 7:40 a.m. to 2:10 p.m., the “regular” group cracked the books from 8:30 a.m. to 3:10 p.m. and the “late” bunch appeared at 9:20 a.m. and stuck around until 4 p.m. The entire eighth grade was placed on the “late” schedule, thus killing off the idea of freedom of choice.

Playing timpani at William Fleming - High School, Roanoke, Virginia

Since the first grade I had gone to school at 8:30 a.m., so arriving at 9:20 made me feel tardy before the day even began. My Mom went to work at the First National Exchange Bank® at 8 a.m. each day, and we lived only two blocks from Fleming, so I began to go over earlier than I had to. It wasn’t long until the magnetism of the band room began to grab hold. Almost every morning week after week, I stood outside the door, caught up in the sounds. I didn’t want to be in the hallway, listening. I wanted to be in the room, playing. However, I did have one small problem. I didn’t know how to play anything.

Two years before, I had spoken to Mom about the possibility of joining the band. The thought of playing drums appealed to me. It didn’t appeal to her. She suggested the trumpet, perhaps because one of my favorite childhood toys was The Golden Trumpet®, a plastic look-alike that could actually make some different sounds. I wasn’t thrilled with the idea, but in the interest of keeping Mom happy, I agreed to go to the band director’s house and try one. Mom arranged that appointment while assisting him with his banking one day. I came to understand that Mom knew everyone of importance on the north side of Roanoke because they came to her window at the branch bank.

I dutifully arrived at the home of Raymond Berwald at the appointed hour. He was a horn player and had led the Fleming Band for several years while also teaching instrumental music in the elementary schools that fed the high school. I gave it my best shot. I puckered, I attempted to buzz and I blew until I thought my skull would crack, but the end result was a sound that resembled a wounded duck. “Son,” he said, “I just don’t think you’re going to be a trumpet player.” In one of many Academy Award-worthy performances that I would give in my life, I looked properly chagrined and trudged homeward. Well, really I raced home, but I did slow down a little before I got to the door. “Sorry, Mom. He said I wasn’t good enough. Now, how about the drums?”

My second attempt at bonding with a pair of drumsticks met with slightly better success. My best friend in the neighborhood was Larry Dickenson, who lived a few doors down the sidewalk. There were twelve duplexes in our L-shaped building. We lived in the fourth from the top of the L, and Larry and his parents lived in the 10th one, after the turn of the architecture. Larry was almost my age, but because his birthday fell late, he was a year behind me in school. A year or two before, he had joined the American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps as a bugler. He was the youngest member in the band. In the very early spring of 1956, he persuaded me to go with him. Actually, he didn’t need to persuade me; he did his best convincing on my Mom. Finally she agreed, and Larry and I went off to the Roanoke American Legion Hall, Post No. 3.

In those days the Legion Hall was the closest thing Roanoke had to a civic auditorium and featured a blend of wrestling matches, country music concerts and large scale church revivals. It was located right in the center of town, across the street in one direction from the famous Hotel Roanoke® and in another direction from the Norfolk and Western® Railway Station. The Drum Corps assembled right on the main floor if the regular practice night had not been usurped by a rental event. Instruments, uniforms, music and other necessary goods were stashed in a storage room in one corner of the building. Larry may have been the youngest in the band, but I was decidedly the smallest guy in the room, a condition that accompanied me for my entire pre-college life. The band leader was a man named Robert Thompson and the drum major was Jesse Wilson. I don’t recall ever learning the name of anyone else. They took one look at me and said, “Do we have a drum that small?” After some searching in the depths of the closet, they found one that had been banished from regular use. “Here, kid. Strap this on and get over there.”

I still had one lingering question. “How do I play it?” The answer: “Just watch the other guys, and do what they do.” So much for in-depth instruction.

After a few weeks I began to get the hang of it. Marching wasn’t difficult. Contrary to today’s elaborate drills, the name of the game for this band was to attempt to get down the street in a straight line without running into something or injuring someone. Turning a corner was an adventure, and anything beyond that was not in the playbook. They issued me a uniform just in time for my big debut performance at the Corps’ annual appearance in the Harrisonburg Memorial Day parade. I managed to get through the day without creating chaos, so it was quite a success. There was no summer schedule, so we shut it down for the year. See you next fall.

Tom with his first percussion teacher, Otis D. Kitchen, band director at William Fleming High School. Photo taken in 1970s.

Not quite. Midway through the summer I awakened to the radio newscast that informed me that the Legion Hall had burned to the ground the previous night, and everything in it had been destroyed. Drums, bugles, uniforms, wrestling mats, popcorn machines – all of it was gone. The building that had housed everything from Gene Autry and an unknown Elvis Presley to Marian Anderson and Messiah performances was reduced to rubble. No attempt was ever made to rebuild the structure or the Corps. Hotel Roanoke grabbed the property for expanded parking. My drumming career was back on the shelf.

That fall I entered the eighth grade at Fleming and, with the feel of drumsticks still fresh in my fingers, again tried to persuade Mom to let me try for the band. I had described my interest in listening to the band’s morning practices, but she had a vision of a 40-foot bass drum sitting in our living room, and she wasn’t yet convinced. This time she suggested the clarinet. Oh well, anything to keep Mom happy. One day after school, I asked Carol Hoffman, a classmate, to let me try her clarinet. She agreed, assembled it and handed it over. I received it with about the same amount of enthusiasm as if someone had handed me a snake. Fortunately for me, I was even worse on the clarinet than I had been on the trumpet. Whereas the trumpet had sounded like a wounded duck, the clarinet didn’t sound at all. Nothing. Zilch. Nada. I couldn’t make a sound on it, even when I actually tried. To this day, the relationship between that reed and that mouthpiece remains a mystery to me. “Gee, Mom. Looks like I’m not a woodwind player either.”

Ray Berwald had suddenly resigned as Fleming’s band director in August 1956. The system hired Otis Kitchen, a man straight out of the Army who had earned a degree from Bridgewater College and would later earn his Master’s from Northwestern University. He was in the very early stages of remaking the group into a real musical unit. Unknown to me at the time, Mom had made his acquaintance, where else, at the bank. She spoke with him, and he agreed to start giving me lessons after the Christmas break. Otis was a keyboard and clarinet player, but he was fundamentally a brilliant musician, and the basics that he taught me proved to be right on target as I developed. He introduced me to a few concepts that had eluded me in the Legion Drum Corps – things like reading music, proper hand position and a sense of ensemble. I had always been a quick learner, and the relationship between mathematics and music seemed very logical to me, so learning to read rhythm was easy. He continually asked if I understood or had any questions. He seemed surprised when I kept saying no, but when I consistently played the right rhythms, he became convinced. Hand position was a little more difficult, but it came along. Doing single strokes seemed easy enough, but I couldn’t seem to maintain control of the sticks when I tried to get them to bounce. As a teacher years later, I came to understand that all beginning drummers run into that wall, but it didn’t soften the blow at the time. One afternoon while practicing on my drum pad, it finally came. It sounds corny to say that suddenly the light turned on, but that’s exactly what happened. One minute the sticks were fighting back, and the next they were doing what I wanted them to do. “Hey, Mom. I got it!”

After a few weeks, Otis said it was time to come inside the room. He put me in the drum section to observe and finally started letting me play a few parts with the band. There were a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 29.7.2013 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Musik ► Instrumentenkunde |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-62287-368-8 / 1622873688 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-62287-368-5 / 9781622873685 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich