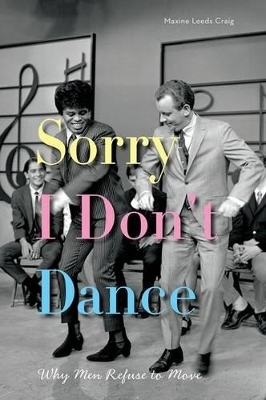

Sorry I Don't Dance

Why Men Refuse to Move

Seiten

2013

Oxford University Press Inc (Verlag)

978-0-19-984529-3 (ISBN)

Oxford University Press Inc (Verlag)

978-0-19-984529-3 (ISBN)

That men don't dance is a common stereotype. As one man tried to explain, "Music is something that goes on inside my head, and is sort of divorced from, to a large extent, the rest of my body." How did this man's head become divorced from his body? While it may seem natural and obvious that most white men don't dance, it is actually a recent phenomenon tied to the changing norms of gender, race, class, and sexuality. Combining archival sources, interviews, and participant observation, Sorry I Don't Dance analyzes how, within the United States, recreational dance became associated with women rather than men, youths rather than adults, and ethnic minorities rather than whites.

At the beginning of the twentieth century and World War II, lots of ordinary men danced. In fact, during the first two decades of the twentieth century dance was so enormously popular that journalists reported that young people had gone "dance mad" and reformers campaigned against its moral dangers. During World War II dance was an activity associated with wholesome masculinity, and the USO organized dances and supplied dance partners to servicemen. Later, men in the Swing Era danced, but many of their sons and grandsons do not. Turning her attention to these contemporary wallflowers, Maxine Craig talks to men about how they learn to dance or avoid learning to dance within a culture that celebrates masculinity as white and physically constrained and associates both femininity and ethnically-marked men with sensuality and physical expressivity. In this way, race and gender get into bodies and become the visible, common sense proof of racial and gender difference.

At the beginning of the twentieth century and World War II, lots of ordinary men danced. In fact, during the first two decades of the twentieth century dance was so enormously popular that journalists reported that young people had gone "dance mad" and reformers campaigned against its moral dangers. During World War II dance was an activity associated with wholesome masculinity, and the USO organized dances and supplied dance partners to servicemen. Later, men in the Swing Era danced, but many of their sons and grandsons do not. Turning her attention to these contemporary wallflowers, Maxine Craig talks to men about how they learn to dance or avoid learning to dance within a culture that celebrates masculinity as white and physically constrained and associates both femininity and ethnically-marked men with sensuality and physical expressivity. In this way, race and gender get into bodies and become the visible, common sense proof of racial and gender difference.

Maxine Leeds Craig is Associate Professor of Women and Gender Studies at the Univeristy of California, Davis. She is the author of Ain't I a Beauty Queen?: Black Women, Beauty, and the Politics of Race.

Acknowledgements ; Chapter 1: Searching for Dancing Men ; Chapter 2: The New Woman and the Old Man ; Chapter 3: Becoming White Folk ; Chapter 4: Dancing in Uniform ; Chapter 5: Managing the Gaze ; Chapter 6: Stepping On and Across Boundaries ; Chapter 7: Sex or "Just Dancing" ; Chapter 8: Conclusions ; Appendices ; Notes ; Bibliography ; Index

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.12.2013 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 9 b/w halftones |

| Verlagsort | New York |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 235 x 157 mm |

| Gewicht | 358 g |

| Themenwelt | Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Theater / Ballett |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Tanzen / Tanzsport | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Gender Studies | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Mikrosoziologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-19-984529-8 / 0199845298 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-19-984529-3 / 9780199845293 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Mehr entdecken

aus dem Bereich

aus dem Bereich