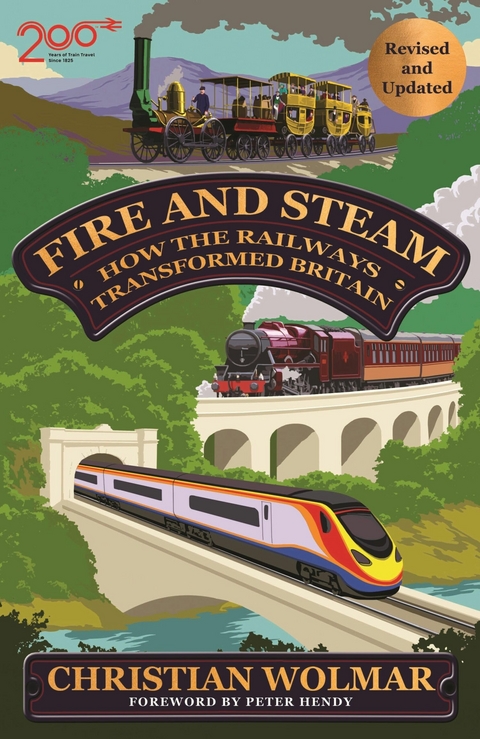

Fire and Steam (eBook)

384 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-84887-261-5 (ISBN)

Christian Wolmar is a writer and broadcaster. He is the author of The Subterranean Railway (Atlantic Books). He writes regularly for the Independent and Evening Standard, and frequently appears on TV and radio on current affairs and news programmes. Fire and Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain was published by Atlantic Books in 2007.

Christian Wolmar is Britain's foremost writer and broadcaster on transport matters. He writes regularly for a variety of publications including the Independent, Evening Standard and Rail magazine, and appears frequently on TV and radio as a commentator. His other books include TheGreat Railway Revolution, The Subterranean Railway, Engines of War and Blood, Iron and Gold.

FIRE & STEAM

INTRODUCTION

WHY RAILWAYS?

One of the least known facts about Louis XIV is that he had a railway in his back garden. The Sun King used to entertain his guests by giving them a go on the Roulette, a kind of roller-coaster built in the gardens of Marly near Versailles in 1691. It was a carved and gilded carriage on wheels that thundered down a 250-metre wooden track into the valley, and, thanks to its momentum, up the other side. The passengers would enter the sumptuous carriage from a small building in the classical style that could lay claim to being the world’s first railway station. Then three bewigged valets would push the coach to the top of the incline, giving the overdressed aristocrats a frisson as it whooshed like a toboggan down the hill.

There were other, rather more prosaic railways in the seventeenth century, too, mostly serving mines. Indeed, there had been ‘tramways’ or ‘wagon ways’ (often spelt ‘waggon ways’) for hundreds of years. The notion of putting goods in wagons that were hauled by people or animals along tracks built into the road is so old that there are even suggestions that the ancient Greeks used them for dragging boats across the Isthmus of Corinth. In Britain, the history of these wagon ways stretches back at least to the sixteenth century when, in the darkness of coal and mineral mines, crude wooden rails were used to support the wheels of the heavy loaded wagons and help guide them up to the surface. The logical extension of the concept was to run the rails out of the mine to the nearest waterway where the ore or coal could be loaded directly onto barges, and as early as 1660 there were nine such wagon ways on Tyneside alone, and several others in the Midlands.1 By the end of the seventeenth century, the tramways were so widespread in the north-east of England that they became known as ‘Newcastle Roads’.

These inventions preceded the railway age. They were nothing like the pioneering and revolutionary invention which finally emerged in the first half of the nineteenth century with the opening of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830, and, as a prelude, the Stockton & Darlington in 1825, five years earlier. As with all such innovations, the advent of the railways was rooted in a series of technological, economic and political changes that stretched back decades, even centuries. Each component of a railway required not only an inventor to think up the initial idea, but several others to improve on the concept through trial and error and experimentation. These developments were not linear; there were a lot of dead ends, technologies that did not work and ideas that were simply not practical. Heroic failures are a sad but necessary part of that process and for every James Watt or George Stephenson who is remembered today, there are countless other unknowns, who together may have made a substantial contribution to the invention of the biggest ‘machine’ of all, the rail network.

It was not only knowledge and technology that were needed to create a railway. There was the baser requirement of capital – lots of it – that would enable engineers to turn this plethora of inventions and concepts into an effective transport system. The brave investors who raised the vast amounts required to build a railway were taking a plunge in the dark by putting their money into an unknown concept and it was not really until the beginning of the nineteenth century, with the Industrial Revolution in full swing, that such funds became available. Then there was the difficult matter of harnessing a better source of power than the legs and backs of men and beasts. It was, of course, steam that was to make the concept of rail travel feasible. The first engines driven by steam were probably devised by John Newcomen,2 an eighteenth century ironmaster from Devon, although in the previous century, a French scientist, Denis Papin, had already recognized that a piston contained within a cylinder was a potential way of exploiting the power of steam. Newcomen used the improved version of smelting iron that had recently been invented and developed the idea into working engines that could be used to pump water from mines. His invention was crucial in keeping the tin and copper ore industry viable in Cornwall, since all the mines had reached a depth at which they were permanently flooded and existing water-power pumps were insufficient to drain them. By 1733, when Newcomen’s patents ran out, he had produced more than sixty engines. Other builders in Britain manufactured 300 during the next fifty years, exporting them to countries such as the USA, Germany and Spain. One was even purchased to drive the fountains for Prince von Schwarzenberg’s palace in Vienna.

Working in the second half of the eighteenth century, James Watt made steam commercially viable by improving the efficiency of engines, and adapting them for a wide variety of purposes. Boulton & Watt, his partnership with the Birmingham manufacturer Matthew Boulton, became the most important builder of steam engines in the world, providing the power for the world’s first steam-powered boat, the Charlotte Dundas, and ‘orders flooded in for engines to drive sugar mills in the West Indies, cotton mills in America, flour mills in Europe and many other applications’.3 Boulton & Watt had cornered the market by registering a patent which effectively gave them a monopoly on all steam engine development until the end of the eighteenth century. Steam power quickly became commonplace in the nineteenth century: by the time the concept of the Liverpool & Manchester railway was being actively developed in the mid-1820s, Manchester alone had the staggering number of 30,000 steam-powered looms.4

However, putting the engines on wheels and getting such a contraption to haul wagons presented a host of new problems. There had been several unsuccessful attempts to develop a steam locomotive, starting with Nicholas Cugnot’s fardier5 in Paris in 1769, which was declared a danger to the public when it hit a wall and overturned. It gets mentioned in motor car histories as, arguably, the world’s first automobile. Several devices to run on roads were built in the late eighteenth century but none met with any success due to technical limitations or their sheer weight on the poor surfaces.

It is Richard Trevithick, a Cornishman, who has the strongest claim to the much-disputed accolade of ‘father’ of the railway steam locomotive. Whereas Boulton & Watt had insisted on building only low-powered engines, Trevithick developed the concept of using high pressure steam, from which he could obtain more power in proportion to the weight of the engine and this opened up the possibility of exploiting his other notion, making the device mobile. Rather than developing power for static wheels, these engines could provide the energy to move themselves. His first effort was a model steam locomotive built in 1800 and a year later he produced the world’s first successful steam ‘road carriage’. It was, though, to be short-lived. Trevithick had not devised a proper steering mechanism and on the way to parade the machine to the local gentry, it plunged into a ditch. The assorted party went off to drown their sorrows in the pub, forgetting to douse the fire under the boiler. The resulting explosion presumably cut short their drinking session.

Despite such mishaps, Trevithick built an improved steam engine in 1802 and took the crucial next step of putting it on rails at Coalbrookdale, an iron works in Shropshire,6 which not only obviated the need for steering but also provided a more stable base than the road. Rails, too, had progressed from the simple wooden planks of the seventeenth century by strapping iron to the wood. L-shaped rails were developed to keep the wheels aligned, but the crucial idea of putting a flange all around the wheel – a lip to prevent derailment – only began to be developed in the late eighteenth century. In 1803, travelling on these crude early rails, Trevithick’s engine managed to haul wagons weighing nine tons at a speed of five miles an hour at another iron works, Pen-y-Darren in Wales. This was certainly a world first even if the locomotive proved too heavy for the primitive rails and was soon converted into a stationary engine.

This suggests the answer to a fundamental question about the history of the railways: why did these iron roads (as they are called in every language other than English) evolve and spread across the United Kingdom and the rest of the world some sixty years before self propelled vehicles, what we now call motor cars? The main reason was that the roads were awful. The well-engineered highways built by the Romans had been allowed to decline for more than 1,000 years and it was only in the early eighteenth century that any attempts at maintaining trunk roads properly began. The old system of making parishes responsible for the maintenance of roads, even major through routes, within their area, with free labour having to be supplied annually by the parish folk, was replaced by a network of Turnpike Trusts, groups of local people who would maintain a road in return for the payment of a toll by anyone using it. By 1820, virtually all trunk routes and many cross-country roads came within this system which led to great improvements. For example, the journey between London and Edinburgh took less than two days compared with a fortnight a century previously. Exeter could be reached from London in seventeen and a half hours, an average speed of 10 mph, and for a brief period, with the introduction of the mail coach in 1784, stagecoaches enjoyed a heyday...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2009 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Schienenfahrzeuge |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Wirtschaftsgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Andrew Roberts • Anthony Beevor • Blood • Blood, Iron and Gold • British Rail • Engines of War • Fire and Steam • How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever • How the Railways Transformed Britain • How the Railways Transformed the World • Iron and Gold • Locomotives • locomotives in detail • locomotives of the southern railway • Patrick Bishop • Peter Ackroyd • railway books • Railways • Simon Winchester • southern railway • The Great Railway Revolution • The Story of the Trans-Siberian Railway • The Subterranean Railway • To the Edge of the World • Trains • trains book • Trans-siberian railway |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84887-261-5 / 1848872615 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84887-261-5 / 9781848872615 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich