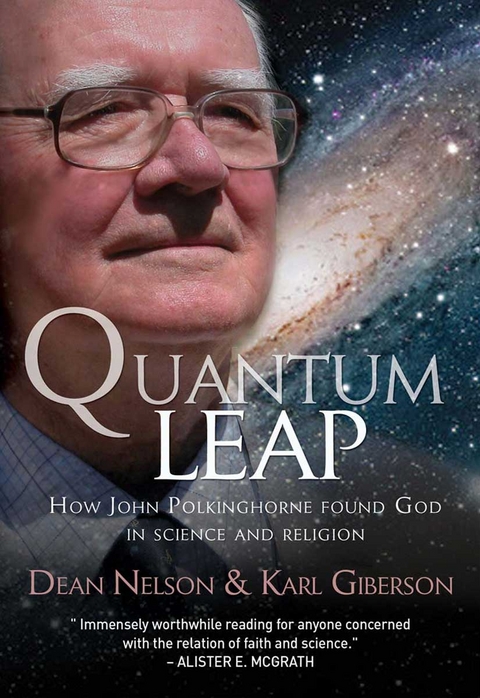

Quantum Leap (eBook)

192 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-85721-128-6 (ISBN)

Quantum Leap uses key events in the life of Polkinghorne to introduce the central ideas that make science and religion such a fascinating field of investigation. Sir John Polkinghorne is a British particle physicist who, after 25 years of research and discovery in academia, resigned his post to become an Anglican priest and theologian. He was a professor of mathematical physics at Cambridge University, and was elected to the Royal Society in 1974. As a physicist he participated in the research that led to the discovery of the quark, the smallest known particle. This cheerful biography-cum-appraisal of his life and work uses Polkinghorne's story to approach some of the most important questions: a scientist's view of God; why we pray, and what we expect; does the universe have a point?; moral and scientific laws; what happens next?

CHAPTER TWO

Room for Reality

World War II witnessed countless messages. Some precipitated great movements of troops and hardware; some contributed to long-range strategy; some were created to deceive. Cryptographers on both sides worked feverishly to code and decode the communications going back and forth. The majority of the messages of this war were small communications however – often a simple letter or telegram letting a family know that one of their loved ones was missing in action, or else had been killed.

Peter Polkinghorne, John’s older brother, fought in the Royal Air Force. The RAF served so heroically fighting the Nazis that an emotional Winston Churchill was moved to immortalize their effort with these famous words: “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” Peter Polkinghorne’s fighter plane, like so many others, went missing somewhere in the North Atlantic. Shortly afterwards, the Polkinghorne family received one of those tragic messages that had been sent to so many other families. Their response, so common in homes all over the world during World War II, was to pray.

John was twelve at the time the message about his brother arrived in 1942. He prayed to God that Peter would be found. Maybe the squadron had just been blown off course, the family reasoned. The weather had been terrible, after all. And Peter was an expert pilot. Surely he would have figured out a way to survive and eventually return to his family, armed with tales of great adventure. God would surely save Peter. Look at all the people praying for him!

The hope that the squadron would be found lasted two days. Peter and John’s father came home early from work, his face the color of a warship’s hull. It was clear that Peter and the others in his plane were at the bottom of the Atlantic. John burst into tears. His mother, an active member of the local Anglican parish, felt that God had let her down. She resented God’s failure to prevent Peter’s death. When the parish vicar came to the house to pray with her, she refused. Reflecting on this nearly sixty years later, Polkinghorne adds, wryly, “But she also didn’t like that vicar.”

Peter was just twenty-one when he died. Before the war, he had been impressed by the academic potential he saw in his little brother, even calling John “professor” in his letters. “I was, of course, greatly saddened at the time of his death,” John recalls, “but recovered in the way that twelve-year-old boys do, not because they are heartless but because they live so much in the unfolding present.”1 Today, almost seven decades later, Polkinghorne continues to live in the unfolding present.

Street, the town where the Polkinghorne family lived during the war, was in Somerset, near the port city and manufacturing center of Bristol, a popular target for German bombing runs. John and his parents would be awakened at night by air raid sirens, and then lie awake listening to the German planes fly overhead, drop their bombs, and then return to Germany. Sometimes the family hid under their staircase. Later at night they could see the glow of Bristol on fire. Occasionally the planes even went overhead during the day.

John was eight when the war began. “I didn’t have a realistic view of the war as a child,” he said. “I saw it as a drama – a scary reality that I was carried away with.”

Peter was the second child that the Polkinghorne family had lost. Before John was born, his sister Ann had died at six months from an intestinal blockage. Because of complications during her pregnancy, doctors recommended against John’s mother having any more children. “She was bold enough to ignore their advice,” he said.2 It was difficult for his mother to be with other families that had more than one child. No photos of Ann were on display in the house, but John’s father routinely visited her grave to keep it tidy. The only time John’s mother saw his father cry was when Ann died – he didn’t even cry at the death of his own mother.

Although John’s mother felt abandoned by God when her two children died, she remained a devout Christian. She was gifted with a welcoming and hospitable spirit to the degree that total strangers would sometimes trust her with their life secrets. She and John’s father, a Post Office employee, took John to church every week. “I cannot recall a time when I was not in some real way a member of the worshipping and believing community of the Church,” he recalls, looking back. “I absorbed Christianity through the pores, so to speak, perhaps to a greater degree than a more direct form of instruction would have conveyed.” John enjoyed church, and liked the vicar (the one his mother didn’t), who, in John’s eyes, had the ability to bring Bible scenes to life.

John also liked school, especially math, where, like so many prodigies, he showed an early aptitude. His mother instilled in him a love for literature, especially Charles Dickens. He did not fare so well with music. Full of self-confidence because of his other school successes, Polkinghorne remembers taking a music test at the neighborhood Quaker school, anticipating he would again receive the top grade in the class. Most of his answers, however, turned out to be wrong. He was humiliated at this ignominious introduction to his personal limitations.

As with Dickens, he developed an appreciation for Shakespeare, literature, and some poems. But the world’s true poetry, he slowly discovered, was more clearly displayed in an elegant mathematical equation than in a well-crafted verse. “There is a thrill in encountering a beautiful equation which I believe is a genuine, if rather specialized, form of aesthetic experience,” he said, echoing a sentiment that mathematicians have shared since Pythagoras first began to celebrate the glories of numbers twenty-five centuries earlier.3 Polkinghorne loved the clarity of the specific, the elegant symmetry and “rightness” of mathematics, in contrast to the vague symbolism of poetry.

Grief over Peter’s death had some unspoken, if not inevitable consequences for John. He was the only child left of three, and a pressure to achieve took hold, as if he had inherited an obligation to contribute to the world on behalf of his deceased siblings. He obsessed over being the best student in his classes, and came to expect his name to be always at the top of every list. Once, he missed several days of elementary school because of bronchitis, which resulted in some of his grades being unavailable for a critical grading period. When the rankings came out, there were three names ahead of his on the roster, which he found most disturbing.

Regardless of the subject, young John dutifully checked his homework over and over before handing it in. Once, as he was turning in a math test, he realized he had misunderstood the directions, and got the entire test wrong. When he explained this to the headmaster, the “daunting man” replied, “If you got the directions wrong, then what chance does the rest of the class have?”

Polkinghorne’s achievements as a youth got the attention of the headmaster of the grammar school, who decided to meet with Polkinghorne’s father. The headmaster said that John would be better served at a school with other high-achieving students, and recommended that the Polkinghornes send their rising mathematical star to the Perse School in Cambridge, where he would be academically stretched. “My parents valued the intellect,” he said. “It got you on in the world. Going to private school meant I was part of an elite group of scholars, which meant a lot to my mother.” It also meant taking a thirty-minute train to Cambridge from Ely (where the family now lived), then a twenty-minute walk from the train station to the school, and then the return trip. The commute kept John from being very active in school events, but he did perform occasionally with the school’s theatre group, play rugby, and edit the school magazine.

The Perse School buzzed with high achievers working toward getting their School Certificates with distinction. “I thought of myself as unremarkable, except for academic achievement,” he said. “I didn’t need any outside pressure to motivate me.”

It was here that the young John’s love for mathematics – he called it “an entrancing subject” – took off. Like generations of mathematicians before him he found that what was opaque and incomprehensible one week was clear and obvious by the next. This led to increasingly complicated thinking as he solved ever more complex equations. His capabilities measurably increased by the week and he acquired a growing sense of what mathematicians refer to as their “power”. This trajectory could take him only to university, and most science-minded achievers at that time looked toward Cambridge rather than its rival, Oxford. John’s teachers and headmaster advised him to apply to Trinity, one of the colleges in the University of Cambridge, where the most famous of all mathematicians, Isaac Newton, had studied and then taught 300 years before.

Trinity College had a system where each student was appointed his or her own don, or tutor, who advised and looked after the student. It was the ultimate mentoring arrangement, and the don was...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 10.8.2011 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | none |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Quantenphysik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-128-5 / 0857211285 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-128-6 / 9780857211286 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich