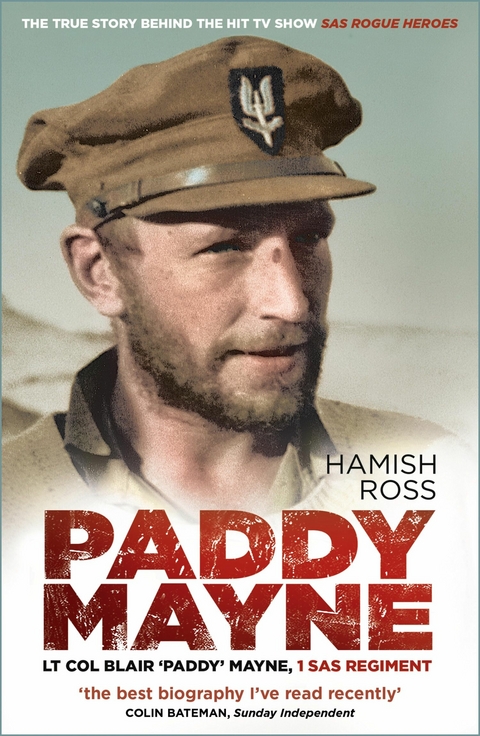

Paddy Mayne (eBook)

336 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-6965-2 (ISBN)

Hamish Ross PhD became interested in the legendary wartime SAS commander Lt Col Blair 'Paddy' Mayne through a boyhood link with one of the 'L' Detachment originals. What started as a journal article soon turned into a far more substantial work when he saw the extent and quality of the archive material available. Hamish lives in Glasgow.

PART I

1

THE LEGEND

Ransom Stoddard: You’re not going to use the story, Mr Scott?

Maxwell Scott: This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

from the film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directed by John Ford

An Irish solicitor, Blair Mayne – or Paddy Mayne as he was more widely known – became one of the most outstanding soldiers and leaders of the Second World War. He had been an international rugby player, who represented Ireland and played for the British Lions before the war; and after serving in a Commando and seeing action in Syria, he joined the new unit that David Stirling was establishing – the Special Air Service. The record of Mayne’s achievements in little over twelve months with the SAS in the North African Desert reads like fiction; yet it is factual and well recorded. The groups he led destroyed over one hundred enemy planes on the ground. These raids, with few exceptions, were carried out on foot and by stealth. Luck was an element in these successes, but the one common factor was Mayne’s ability to read the situation on the ground, anticipate how the enemy would react, and then attack. He was twenty-seven years of age when he won the DSO for the first time. Over the next three years, Mayne led the unit in Sicily and mainland Italy in a very different kind of warfare; then in France, behind enemy lines; and in Germany, where the unit was the spearhead of an armoured thrust. In each of these three campaigns, he added a further bar to the DSO, then received the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur. At the end of the war, after a short period with an Antarctic Survey, Mayne returned to the law, becoming a senior official in the Law Society of Northern Ireland. In 1955, he died in a car accident at the age of forty.

Heroic military figures have long been the subject of public interest, not only because of their achievements, but for what motivates them. There is fascination with the heroic contempt for personal safety that defies common experience; and there is something of an aura of mystery about the hero, which often gives rise to legend. In Mayne’s case, the newspapers began the trend during the war: he was compared to Bulldog Drummond,1 the fictional hero of spy thrillers of the twenties and thirties; and he was also described as a famous pre-war international sporting figure, coolly strolling into an enemy officers’ mess and attacking its occupants, before moving on to the next job; and by the time he was decorated by the king with the third bar to the DSO, they had increased his height by four inches to six feet six. Decades later, first a radio series and then a television programme about Mayne made their contribution with hyperbole.

At the end of the war, though, the first personal accounts began to emerge from those who had served in the SAS. A maxim that has long been established in combat units is that comrades know those who are truly worthy of recognition. Two of Mayne’s colleagues wrote of their time in the SAS: Malcolm James Pleydell,2 its first medical officer, and Fraser McLuskey,3 its first padre. Both men wrote insightfully of Mayne, what manner of man he was, and of the respect and regard in which he was held by his men.

But soon after his death, however, misinformation about Mayne began to appear, first of all in books about others. Keyes somewhat pejoratively attributed to him the authorship of an operational report of a troop’s actions at a Commando raid in Syria,4 which in fact had been written and signed by another officer.5 Two years later, Cowles erroneously claimed that Mayne’s progression from the Commando to the SAS came about when he was rescued after some weeks under close arrest for having punched his superior officer.6 In reality, Mayne had left the unit the previous month.7

The first book about Mayne was written by Patrick Marrinan8 and appeared two years after the claim by Cowles. Marrinan approached his material very much in the tradition of a Boy’s Own account. He had read Cowles’ account of the early SAS and cited from it; and he simply accepted the fanciful tale of how Mayne came to join the SAS, and went on to create a scenario for it. To be fair to Marrinan, at the time he would not have had access to the war diaries which would have given evidence to refute the claim. But, on the other hand, Mayne was his subject (since Marrinan had been a barrister, Mayne was also in a sense his client) and he had read his letters, which, if he had cross-checked with published accounts about No. 11 Commando, at least would have made him question the unfounded claim. Instead, he consolidated a legend: the future leader of the SAS was brought into the light from prison to be offered the opportunity to prove himself and become its greatest warrior. Throughout, Marrinan treated Mayne as a larger-than-life character, personally motivated, whose actions happened to coincide in general with the Allied war effort. It all very neatly fitted the tradition and style from which it was derived. But Marrinan was also nearly contemporary with his subject; and in writing about Mayne’s postwar life, he found that it was too dull to be of interest, for he devoted only ten pages to it. However, he left two references about Mayne which were to prove prescient. He wrote that during Mayne’s lifetime, exaggerated stories about him were widely circulating; and, secondly, he did his best, according to the way society perceived it at the time, to encapsulate Mayne’s state of mind after the war. And there things may well have remained.

However, twenty years later the SAS attack on the Iranian embassy was filmed by television cameras and the regiment became the subject of intense public interest. A generation after Marrinan’s book appeared, Bradford and Dillon wrote about Mayne.9 They too presented him in heroic mould, but they gave their subject a more modern treatment, portraying him as a flawed hero. Not only did they accept the received version of Mayne’s entry to the SAS – via a prison cell – but with them the tale reached its apotheosis; for they postulated that it might have occurred because he was not selected to take part in what became known as the Rommel Raid, and lashed out in anger. In truth, of course, by the time the idea of an attempt to kill or capture Rommel was discussed as an option for No. 11 Commando, Mayne had been out of the unit for three and a half months. Although their treatment was modern, it had overtones of the classical tragic hero of drama who is fatally flawed. Now even assuming a punch had been thrown at a senior officer (junior officers have punched their superiors in the past and will do so in the future), it is hardly an indication of a deep character flaw. But according to Bradford and Dillon’s account, the tendency recurred throughout Mayne’s career, the evidence for which came from anecdotal accounts collected over forty years after the events. Moreover, they portrayed him as something of a serial assailant. For example, they produced a new tale that was not in circulation in Marrinan’s time, the events of which were supposed to have occurred at the end of the desert war. The plausibility of these tales is heightened by their association with a well-known figure – the son of the Director of Combined Operations, or the well-known broadcaster, Richard Dimbleby – but this is also where they fall apart, when dates and movements are analysed. Nonetheless, Bradford and Dillon’s interpretation of Mayne passed into the canon of books about the desert war and the SAS Regiment.

No research into Mayne himself had ever been carried out. And what has characterised references to him in more recent writing has been an uncritical acceptance of a fiction about how he came to join the SAS; and the transference of assumed underlying anger and aggression to the battlefield – with connotations of a latter-day Viking berserker – to account for his heroism. But Stirling did not invite Mayne to join the unit expecting an undisciplined killer: he had been told about Mayne’s leadership of his troop and his tactical skills during a Commando operation at the Litani river. And right from the beginning of the SAS, there was a philosophy concerning the qualities they looked for:

An undisciplined TOUGH is no good, however tough he may be. Most of ‘L’ Detachment’s work is night work and all of it demands courage, fitness and determination of the highest degree and also, and just as important, discipline, skill and intelligence and training.10

One of the earliest written assessments of Mayne by an insider included the quality of Mayne’s judgement and his firm conviction that ‘to take unreasonable risks was to invite disaster’. The SAS Regimental Association obituary of him stated that ‘In spite of his great physical strength, he was no “strong-arm” man.’11 Then, from the evidence of actions for which he was decorated, the personal capabilities which made him so successful were not blind fury or brute strength, but insightfulness, coolness of execution and the willingness to expose himself. Mayne’s first DSO was won in stealth raids, where he achieved the destruction of a great amount of enemy equipment, fuel and bomb dumps – strategic targets – hitting Rommel’s capabilities very heavily; in the early phase of the unit’s operation direct contact with enemy troops was usually avoided, although some specific attacks were made on them. Then one bar to...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.8.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | 1 sad • BBC • British Army • British Lions • Commandos • David Stirling • Lieutenant Colonel Robert Blair Mayne • newtownards • sas rogue heroes • Second World War • Victoria Cross • war diaries • western desert • World War Two • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-6965-7 / 0752469657 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-6965-2 / 9780752469652 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich